Outbreak of Rift Valley Fever among herdsmen linked to contact with body fluids of infected animals in Nakaseke District, Central Uganda, June–July, 2023

Authors: Mariam Komugisha1*, Brian Kibwika1, Benon Kwesiga1, Richard Migisha 1, David Muwanguzi2, Stella Lunkuse2, Joshua Kayiwa2, Luke Nyakarahuka3, 4, Alex Riolexus Ario1; Institutional affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program-Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda; 2Integrated Epidemiology and Surveillance Department, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda; 3Uganda Virus Research Institute, Entebbe, Uganda; 4Department of Biosecurity, Ecosystems and Veterinary Public Health, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; Correspondence: Tel: +256773822356, Email: mkomugisha@uniph.go.ug

Summary

Background: Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a viral zoonosis which occurs sporadically in Uganda. On July 24, 2023, a 24-year-old male para-veterinarian from Kimotozi village, Nakaseke District presented to Mengo Hospital with a 5-day history of intermittent nosebleeds, fever, abdominal, and joint pain; Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) from a blood sample was positive for RVF. We investigated to identify the source, estimate the magnitude, and drivers of the outbreak to inform control and prevention measures.

Methods: We defined a suspected case as a sudden onset of fever (≥38°C), and at least 2 of the following signs and symptoms: headache, skin rash, muscle/joint pain, intense fatigue, dizziness, coughing, abdominal pain, or bleeding in a resident of Nakaseke District from June 1–July 30, 2023. A confirmed case was a suspected case with positive PCR results. We actively searched for case-patients and interviewed them about demographics, symptoms, and animal-related activities. Blood samples from seven case-patients were tested by PCR at Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI). We conducted environmental assessments and interviewed farmers and herdsmen to identify risk factors.

Results: Eight case-patients (2 confirmed), all males, were identified in Kimotozi Village; one (12.5%) died. Median age was 25 years (range 19-28). Symptoms included fever (100%), headache (100%), and bleeding (25%). All case-patients (one para-veterinarian and seven herdsmen) resided and worked on three RVF-affected farms with reports of multiple recent animal abortions and young animal deaths. All had frequent contact with the livestock, including placentas, and drank raw cow milk. Before presenting to Mengo Hospital, the index case visited three health facilities without any suspicion or clinical testing for viral hemorrhagic fevers.

Conclusion: This RVF outbreak likely resulted from contact with infected animals’ fluids. We educated farmers and herdsmen, and restricted animal movement from RVF affected farms. Training clinicians to increase their suspicion index for RVF could reduce delays to diagnosis in the future.

Introduction

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is an acute viral hemorrhagic fever caused by Rift Valley Fever Virus (RVFV), a member of the genus Phlebovirus belonging to the family Bunyaviridae. The virus can be transmitted from infected animals to humans through contact with blood, body fluids, or animal tissues during slaughtering or butchering, assisting with birth in animals, conducting veterinary procedures, or from the disposal of carcasses or fetuses. Transmission can also occur through bites from infected mosquitoes, but person to person transmission has not been documented. Persons who are always in close contact with the animals and animal products such as herders, farmers, and animal health practitioners are at higher risk of infection (1). In animals, RVFV is mainly transmitted by mosquitoes.

The disease has an incubation period of 2–6 days in humans, and those infected may remain asymptomatic, while others might develop mild or severe symptoms. People with mild form may experience signs and symptoms such as fever, sudden onset of flu like signs, body weakness, joint pain, muscle pain, headache, loss of appetite, vomiting, confusion, neck stiffness, sensitivity to light and dizziness. The symptoms of RVF usually last from 4 to 7 days, after which the antibodies can be detected and the virus disappears from the blood. People with severe form of RVF may experience clinical signs and symptoms such as vomiting blood, passing blood in the faeces, a purpuric rash, bleeding from the nose or gums and bleeding from venipuncture sites (2). The overall case fatality rate is <1%. However, in patients with hemorrhagic form, the case-fatality rate is up to 50%.

Rift Valley Fever Virus infects domestic ruminants such as cattle, sheep, and goats in an age-dependent manner, where young animals are more susceptible than adults. In livestock, the disease can cause increased abortions and stillbirths, and high mortality in neonates and young animals leading to significant economic losses (3). There is no specific treatment for RVF in humans and animals, but supportive care may prevent complications and decrease mortality.

Rift Valley Fever Virus was first isolated during an epidemic among sheep in the Rift Valley in Kenya in 1931. Between 2000–2016, wide spread outbreaks have occurred in various countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia, Sudan, Niger, Madagascar, South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Yemen. In Uganda, the first RVF human case was identified in 1968 followed by an outbreak of RVF that occurred in Kabale district in 2016 (4). Uganda has continued to experience an increase in sporadic outbreaks of RVF. From 2016 to 2018, 10 independent outbreaks occurred in 10 districts (5). The disease is endemic in several regions of the country; a recent study reported a seroprevalence of 11% in animals (6). From 2017 to 2023, RVF was confirmed in 21 districts.

On July 24, 2023, the Uganda National Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) was notified of a suspected Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) by Mengo Hospital through the Event Based Surveillance (EBS) unit. On the same day, the case-patient tested positive for RVF using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) at the Central Public Health Laboratory (CPHL). We investigated to identify the source, estimate the magnitude, and drivers of the outbreak to inform control and prevention measures.

Methods

Outbreak area

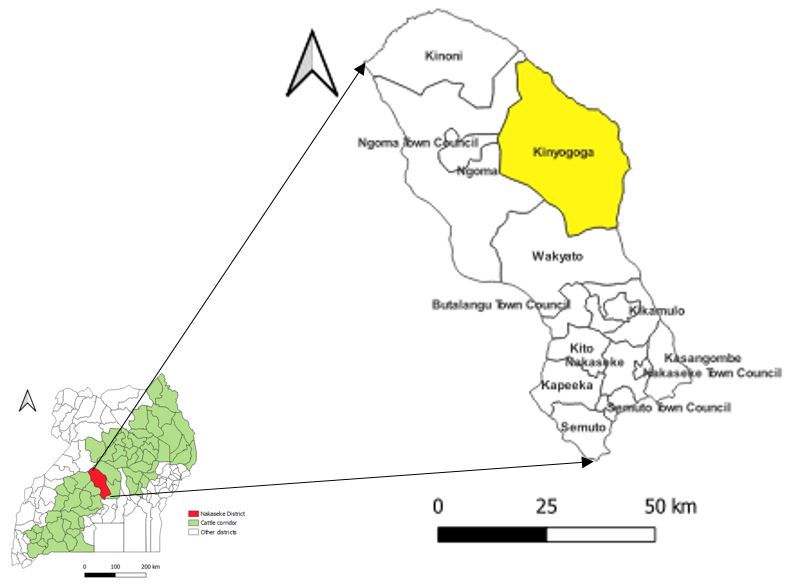

This outbreak occurred in Kinyogoga Subcounty, Nakaseke District (Figure 1). The district is located in Central Uganda; has an estimated population of 254,900 living in 8 sub-counties (7). Rearing of cattle and goats is the main economic activity in the district. Nakaseke District is located in the cattle corridor. The cattle corridor stretches from South-Western through central to north-eastern Uganda, and covers 35% of the country’s land. Livestock production in Uganda is highly concentrated in the cattle corridor.

Case definition and finding

We defined a suspected case as sudden onset of fever (38°C), no clear alternative diagnosis, and at least two of the following signs and symptoms: headache, skin rash, muscle/joint pain, intense fatigue, dizziness, coughing, abdominal pain, or unexplained, bleeding from any site from June 01, 2023 to July 30, 2023 in a resident of Nakaseke District. A confirmed case was defined as a suspected case with Rift Valley Fever Virus identified by PCR.

To identify additional cases, the team visited several health facilities where the index case-patient sought care; reviewed records and interviewed health workers. We interviewed the index case household members and herdsmen on the RVF affected farms (farms which reported high abortions and high mortality rate of young animals). We also used snow-balling to identify additional cases who presented with similar signs and symptoms in the community. We subsequently interviewed case-patients on the date of symptom onset, signs and symptoms, demographics, and exposure history. We line-listed all case-persons identified in the community.

Descriptive epidemiology

During the investigation, we conducted a descriptive epidemiologic analysis of the case-patients by time, person, and place.

Environmental assessment

We conducted assessments at three (3) RVF affected farms where case-patients resided or worked. We assessed for the presence of livestock that had aborted and died suddenly during June –July 2023. We interviewed 9 herd’s men, 3 farmers and 4 animal health practitioners to understand more about the RVF affected farms with high abortions and animal deaths, and risk practices that exposed case-patients to RVFV.

Laboratory investigations

We collected 5 ml of blood from 7 case-patients. The samples were transported to the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) laboratory, Entebbe, Uganda for laboratory testing using Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR).

Ethical considerations

This investigation was in response to a public health emergency (RVF outbreak) and was therefore determined by the US Centers for Disease Control to be non-research and that its primary intent was public health practice or a, epidemic or endemic disease control activity. The Ugandan Ministry of Health through the office of the Director General of Health Services gave the directive and approval to investigate this outbreak. We obtained verbal informed consent from case-patients during this investigation and other interviewed community members that were above 18 years. We ensured confidentiality by conducting interviews in privacy ensuring that no one could follow proceedings of the interview. The questionnaires were kept under lock and key to avoid disclosure of personal information of the respondents to members who were not part of the investigation.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

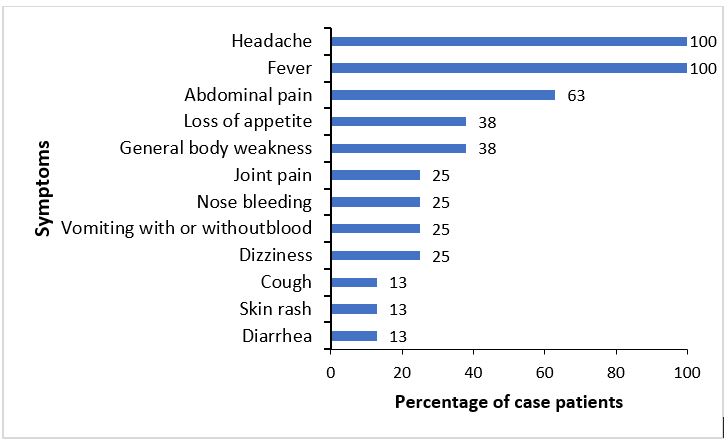

We identified 8 RVF case patients, including 2 confirmed cases and 6 suspected cases. Of the 8 case-patients, one died (case-fatality rate =12.5%). The time to death from symptom onset was 16 days. Among the 8 case-patients with symptom data, common symptoms included fever (100%), headache (100%), and abdominal pain (63%) (Figure 2). The case-patients ranged in age from 19 to 28 years. All (100%) of the case-patients were males. All case patients were residents of Kimotozi village, Kinyogoga subcounty in Nakaseke District. Seven (88%) case-patients were herders (88%) and one (12%) was a para-veterinarian. The index case sought care at four (4) different health facilities where he was managed for gastritis, typhoid, and brucellosis before RVF was suspected and confirmed.

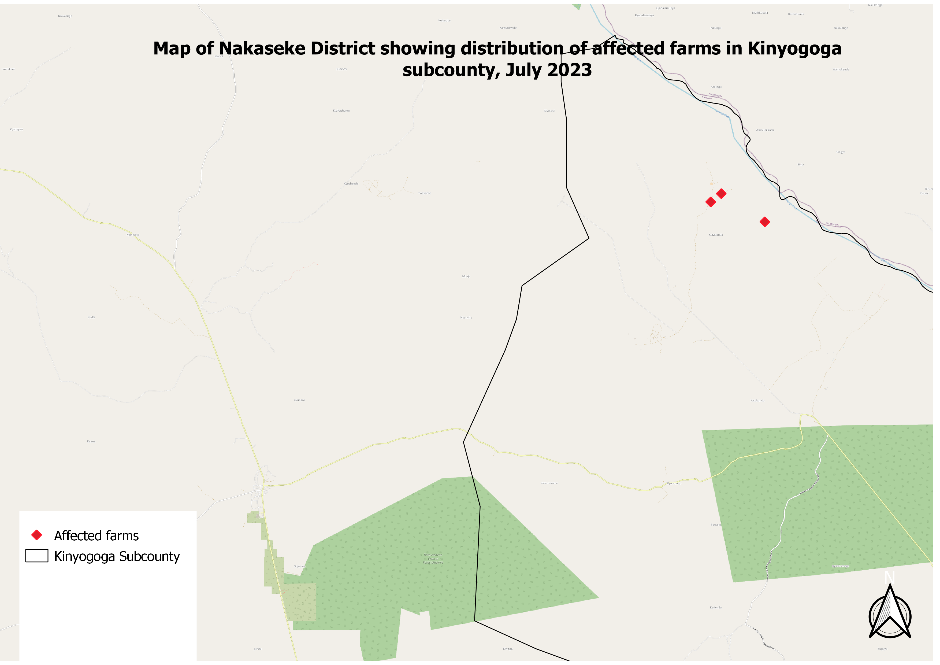

The case-patients resided and worked on the 3 RVF affected farms with multiple abortions and young animal deaths in particular calves, lamb, and kids (Figure 3). The 3 RVF affected farms were neighboring each other, in a single village known as Kimotozi village located in Kinyogoga subcounty, Nakaseke District.

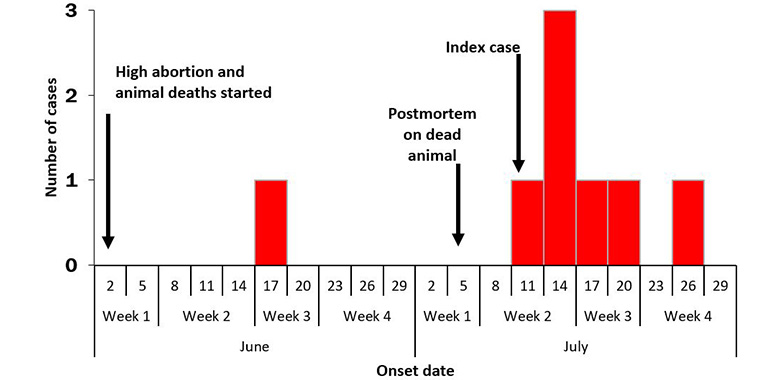

Following high abortion rates among cattle, sheep, and goats, and death of neonates and young animals (goats, sheep and cattle) aged less than 1 year which started in early June throughout the month of July, 2023; human cases started to appear on June 17, 2023. On July 12, the index case of the outbreak appeared in Kinyogoga Subcounty. The case-patients rapidly increased and peaked on July 15, 2023. This epidemic curve suggests a multiple-source outbreak (Figure 4). The onset of cases declined, the last case onset symptom occurred on July 26.

Laboratory investigations

A total of eight (8) human samples were collected. Two of the returned human sample results were PCR positive (positivity rate of 25%). During the outbreak investigation, the team was unable to collect animal samples because of logistical limitations.

Environmental assessment findings

The animals on the three (3) affected farms shared a grazing area and a watering point. Unusual increase in abortion rates and death of young domestic animals (goats, sheep, and calves aged less than one year) were reported on the three affected farms. From June 1 to July 30, 42 young animals died, 36 animals aborted and 8 adult animals died. During this period, the case-patients engaged in assisted animal birth, handling of retained placenta, handling of aborted fetus, and slaughtering of dead animals on the affected farms without using personal protective equipment. There was restricted movement of animals from the three affected farms.

Exposure history

The RVF case-patients had a history of contact with the animals and animal products from RVF affected farms. The case- patients participated in the slaughter and butchering of sick animals, assisting animal birth, handling aborted animal fetus, and retained placenta without wearing personal protective equipment. In addition, they consumed dead animal meat, milked and drank raw milk which increased exposure to RVFV. The RVF index case collected blood samples from sick animals and also conducted post-mortem on sick animals prior to illness.

Discussion

The RVF outbreak occurred in Kimitozi village, Nakaseke District, which resulted in 8 cases and 1 death during June to July, 2023. The outbreak likely resulted from contact with infected animal fluids.

The RVF index case sought care at 4 health facilities where he was diagnosed with gastric ulcer, brucellosis, and typhoid before a VHF was suspected by the clinicians after 12 days of seeking health care. The delay in detection could have been worse with other VHFs such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever which is endemic to Nakaseke District with a higher case fatality rate and capable of person-to-person transmission (8). Early suspicion and laboratory diagnosis can help in the early detection of the disease, early supportive treatment and recovery of the infected persons. Our findings highlight the need to improve access to diagnostic services, educating the clinicians about VHFs in humans, creating awareness among clinicians on the possibility of co-infections with other highly infectious pathogens such as RVF, and also enhancing surveillance of VHFs in humans and animals in Uganda.

The outbreak was linked to contact with infected animals’ fluids during slaughtering, butchering, assisted animal birth, handling of aborted fetus, and milking of sick animals without using personal protective equipment. Case-patients also consumed raw milk and dead animal meat which increased the risk of acquiring RVF disease. This is consistent with the study conducted in South Africa (9). Livestock in particular cattle, sheep, and goat act as reservoirs for RVFV, and play a vital role in the transmission of zoonotic diseases such as RVF to humans (10, 11).

Herders and a para-veterinarian were affected by the outbreak. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), occupational groups such as herders, and veterinarians are at higher risk of acquiring zoonotic diseases such as RVF disease (12) because of frequent contact with live animals and their products. There is a possibility that the human cases, in particular herdsmen got exposed to RVFV through bites from infected mosquitoes, most commonly Aedes and Culex mosquitoes, since they herd in busy areas. There is need for targeted interventions such as creating awareness on the transmission and prevention of zoonotic diseases among the high- risk. This could reduce the chances of exposure to highly infectious zoonotic diseases such as RVF. Hence, preventing future RVF outbreaks, and also minimizing the effect of RVF outbreaks.

The investigation found that the outbreak affected only males and young adults aged 19-28 years. In cattle keeping communities; males play gender roles such as grazing and slaughtering of animals which increases the risk of zoonotic disease transmission from animals to males compared to females (13). The young adults have frequent participation in livestock-related activities such as grazing, slaughtering and butchering of animals. A study conducted in Kabale District, Western Uganda, in 2016, found no antibodies against RVFV among individuals younger than 19 years (4). Exposure prevention strategies for RVF should target towards males and young adults.

The study found a higher case-fatality rate of 12.5% compared to previous outbreaks (14, 15). Additionally, less than 1% of humans infected with RVF die of the disease according to the World Health Organization(1). The higher CFR in this study could have resulted from under-detection of RVF cases because majority of the RVF cases maybe asymptomatic.

We found out that there was no One health collaboration between the human health and veterinary teams at district level which affected information sharing and timely detection of RVF outbreak. There is need to strengthen collaboration among the human health, veterinary and environmental officials through establishment of a District One Health team (DOHT) in Nakaseke District to enable effective response to zoonotic diseases in particular RVF at district level.

Study limitations

We may have underestimated the magnitude of the outbreak because majority of the RVF cases may exhibit mild or no symptoms of RVF(16, 17). We were unable to collect animal samples because of logistical limitations. Therefore, unable to confirm and also determine the magnitude of RVF in animals. However, we based on the fact that RVF causes high abortion and death of young animals to identify the RVF affected farms. All case-patients worked and resided on the RVF affected farms.

Conclusion

The investigation revealed that there was Rift Valley Fever outbreak in Nakaseke, Uganda. The outbreak was linked to contact with infected animals and their body fluids. The outbreak revealed that the suspicion index for VHFs is still low among clinicians, and the animal disease surveillance system is still weak to enable timely detection of zoonotic diseases in animals before they cross over to humans. We educated communities with focus on high risk groups such as herds men, veterinary practitioners and farm owners in Nakaseke district on the signs and symptoms, transmission and preventive measures for RVF; were we encouraged use of PPE such as gloves during handling of animal products and consumption of boiled milk.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contribution

All authors contributed to the write-up and review of the bulletin. MK wrote the drafts of the bulletin and revised the paper for substantial intellectual content. MK, BK, JK, and LN participated in the investigation of RVF in Nakaseke District and reviewed the paper for substantial intellectual content. LN, SL, and DM were involved in the review of the bulletin for substantial intellectual content. BK, RM, and ARA participated in the supervision of field data collection and reviewed the draft bulletin for substantial intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final version of the bulletin.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff of the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program for the technical support and guidance offered during this study. The authors also extend their appreciation to Nakaseke District team for the support they offered during the investigation. We appreciate the Uganda Virus Research Institute for testing all samples and the timely release of laboratory results. Finally, we thank the US-CDC for supporting the activities of the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program.

Copyright and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin are in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- World Health Organization. Rift Valley Fever 2018 [23/August/2023:[

- Hartman A. Rift Valley Fever. Clinics in laboratory medicine. 2017;37(2):285-301.

- Wright D, Kortekaas J, Bowden TA, Warimwe GM. Rift Valley fever: biology and epidemiology. The Journal of general virology. 2019;100(8):1187-99.

- Nyakarahuka L, de St Maurice A, Purpura L, Ervin E, Balinandi S, Tumusiime A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Rift Valley fever in humans and animals from Kabale district in Southwestern Uganda, 2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(5):e0006412.

- Luke N, Balinandi S, Mulei S, Kyondo J, Tumusiime A, Klena J, et al. Ten outbreaks of rift valley fever in Uganda 2016-2018: epidemiological and laboratory findings. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;79:4.

- Tumusiime D, Isingoma E, Tashoroora OB, Ndumu DB, Bahati M, Nantima N, et al. Mapping the risk of Rift Valley fever in Uganda using national seroprevalence data from cattle, sheep and goats. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(5):e0010482.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Population and Censuses, population by sex for 146 districts 2022 [Available from: https://www.ubos.org/explore-statistics/20/.

- Mirembe BB, Musewa A, Kadobera D, Kisaakye E, Birungi D, Eurien D, et al. Sporadic outbreaks of crimean-congo haemorrhagic fever in Uganda, July 2018-January 2019. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(3):e0009213.

- Msimang V, Thompson PN, Jansen van Vuren P, Tempia S, Cordel C, Kgaladi J, et al. Rift Valley Fever Virus Exposure amongst Farmers, Farm Workers, and Veterinary Professionals in Central South Africa. Viruses. 2019;11(2).

- Rahman MT, Sobur MA, Islam MS, Ievy S, Hossain MJ, El Zowalaty ME, et al. Zoonotic Diseases: Etiology, Impact, and Control. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9).

- Samad M. Public health threat caused by zoonotic diseases in Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Veterinary Medicine. 2011;9(2):95-120.

- Adam-Poupart A, Drapeau LM, Bekal S, Germain G, Irace-Cima A, Sassine MP, et al. Occupations at risk of contracting zoonoses of public health significance in Québec. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada. 2021;47(1):47-58.

- Whitehouse ER, Bonwitt J, Hughes CM, Lushima RS, Likafi T, Nguete B, et al. Clinical and epidemiological findings from enhanced monkeypox surveillance in Tshuapa province, Democratic Republic of the Congo during 2011–2015. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2021;223(11):1870-8.

- Laughlin LW, Meegan JM, Strausbaugh LJ, Morens DM, Watten RH. Epidemic Rift Valley fever in Egypt: observations of the spectrum of human illness. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1979;73(6):630-3.

- Ramadan OPC, Berta KK, Wamala JF, Maleghemi S, Rumunu J, Ryan C, et al. Analysis of the 2017-2018 Rift valley fever outbreak in Yirol East County, South Sudan: a one health perspective. The Pan African medical journal. 2022;42(Suppl 1):5.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rift Valley Fever 2023 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/rvf/index.html.

- Birungi D, Aceng FL, Bulage L, Nkonwa IH, Mirembe BB, Biribawa C, et al. Sporadic Rift Valley Fever Outbreaks in Humans and Animals in Uganda, October 2017–January 2018. Journal of Environmental and Public Health. 2021;2021:8881191.

Comments are closed.