COVID-19 Outbreak among Refugees in Nyakabande Transit Centre, Kisoro District, Uganda, June-July 2022

Authors: Peter Chris Kawungezi1*, Robert Zavuga1, Brendah Simbwa Nakafeero1, Jane Frances Zalwango1, Mackline Ninsiima1, Thomas Kiggundu1, Brian Agaba1, Lawrence Oonyu1, Richard Migisha1, Irene Kyamwine1, Daniel Kadoobera1, Benon Kwesiga1, Lilian Bulage1, Robert Kaos Majwala2,3, and Alex Ariolexus Riolexus1; Institutional affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, 2Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda, 3Department of Global Health Security, Baylor Uganda, 4Division of Global Health Protection, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Kampala, Uganda; Correspondence*: Tel: +256783401306, Email: peter@uniph.go.ug

Summary

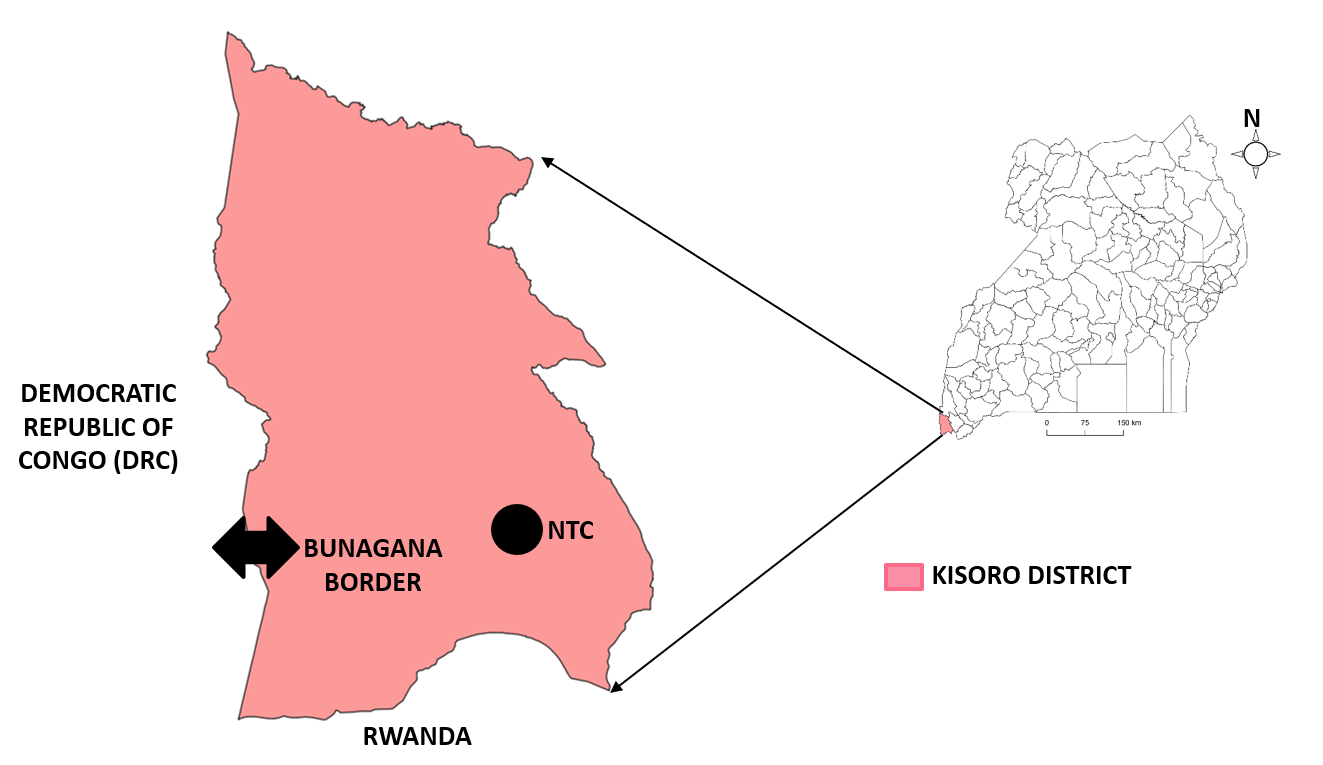

Background: Nyakabande Transit Centre (NTC) is a temporary shelter for refugees arriving in Kisoro District from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Due to conflict in DRC, approximately 34,000 persons arrived at NTC between March and June 2022. On June 12, 2022, Kisoro District reported >330 cases of COVID-19 among NTC residents over a two months’ period. We investigated the outbreak to assess its magnitude, identify risk factors, and recommend control measures.

Methods: We defined a confirmed case as a positive SARS-CoV-2 antigen test in an NTC resident during March 1–June 30, 2022. We generated a line list through medical record reviews and interviews with residents and health workers. We assessed the setting to understand possible infection mechanisms. In a case-control study, we compared exposures between cases (persons staying ≥5 days at NTC between June 26 and July 16, 2022, with a negative COVID-19 test at NTC entry and a positive test at exit) and unmatched controls (persons with a negative COVID-19 test at both entry and exit who stayed ≥5 days at NTC during the same period). We used multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with contracting COVID-19.

Results: Among 380 case-persons, 206 (54.2%) were male, mean age was 19.3 years (SD=12.6); none died. The attack rate (AR) at NTC was higher among exiting persons (3.8%) than entering persons (0.6%) (p<0.01). Among 42 cases and 127 controls, close contact with symptomatic persons (aOR=9.6; 95%CI=3.1-30) increased odds of infection; using a face mask (aOR=0.06; 95% CI=0.02-0.17) decreased odds. We observed overcrowding in shelters, poor ventilation, and most NTC residents not wearing face masks.

Conclusion: A COVID-19 outbreak at NTC was facilitated by overcrowding and failure to use facemasks. Enforcing face mask use and expanding shelter space could reduce the risk of future outbreaks. The collaborative efforts resulted in successful health sensitization and expanding the distribution of facemasks and shelter space.

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), is a disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)(1). Refugee settings are especially susceptible to outbreaks of infectious diseases, including COVID-19 (2, 3). The susceptibility is linked to overcrowding, inadequate access to clean water and soap, and constraints on hand-washing facilities (3-5). In addition, early detection of the virus is often not possible because monitoring access to the camp is difficult and thus not easy to know whether people infected are camp residents or people from outside the camp (6).

COVID-19 outbreaks have been reported among refugees in Bangladesh (6, 7), Greece(6, 8, 9), and Brazil (10). The COVID-19 preventive measures among refugees are similar to those in the general population, including mass testing, vaccination, social distancing, use of face masks, hand washing, and other measures to improve personal hygiene (4, 7, 11-13). However, the implementation of these measures among refugees may be limited (4, 9, 10). Additional measures including refugee-led response in health education have been demonstrated to be beneficial (14).

Uganda hosts more than 1.4 million refugees and asylum seekers from neighboring countries, including South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, and Somalia(15). Despite Uganda’s open-door policy and provision of basic services, the large number of refugees has placed a significant strain on the country’s resources and infrastructure, impacting both refugees and host communities. In early 2022, a new influx of more than 10,000 refugees fled to Uganda’s southwestern Kisoro District due to violent clashes in DRC. Refugees entered through the Bunagana border and were relocated to Nyakabande Transit Centre (NTC) (16). In April 2022, the NTC registered its first case of COVID-19 through mandatory screening at entry and exit. By August 30, 2022, together with the Bubukwanga Transit Center in Bundibugyo District, the two registered a total of 1,365 COVID-19 cases(17).

Following the identification of the index COVID-19 case-patient on April 04 2022 in NTC, the cases cumulatively increased to 621 by June 30, 2022. We investigated the outbreak to establish its scope, identify factors associated with COVID-19 infection in NTC, and to recommend control and preventive measures for the future.

Methods

Outbreak area

Nyakabande Transit Centre is located 5km from Kisoro Town and 18 Kilometers from Bunagana Border in Kisoro District, South West Uganda. Kisoro District shares boundary with Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in the West and the Republic of Rwanda in the South. It was opened in 1994 to cater for both returning and arriving refugees for Rwandans fleeing the genocide. In 2022, the capacity of NTC was 825 individuals. At the holding area, refugees are free to proceed to NTC or return to their home country. Refugees are supposed to stay for a period of 2-5 days in the transit centre then transferred to settlement camps. However, due to the influx, this was not the case as some refugees stayed in the transit centre longer.

All refugees were mandated to be tested for COVID-19 at entry to NTC, and at the time of exit to the resettlement camp. Refugees were also mandated to be vaccinated against COVID-19 at the time of relocation to the resettlement camp. In early April 2022, NTC management designated one shelter for isolation of COVID-19 confirmed case patients.

Case definition and case finding

We defined a confirmed case as a positive COVID-19 antigen test (SD Biosensor, Inc., Republic of Korea) in a resident of NTC during March 1–June 30, 2022. We abstracted data from the COVID19 laboratory testing and isolation registers using a data abstraction tool to identify case-patients for the COVID-19 tests at entry and exit of NTC. Between March 28, 2022 and June 26, 2022, data was collected on the total number of refugees tested for COVID-19 at entry and exit, as well as the total number of positive test results at both entry and exit to determine when refugees were testing positive in relation to their stay at the transit Centre and to identify whether the COVID-19 cases were imported or contracted while at the Centre.

Descriptive epidemiology

Environmental assessment

We assessed the NTC premises to understand the setting and the COVID-19 isolation unit. We observed sanitation and hygiene practices, availability of water, hand washing facilities, use of facemasks, crowding, the structure and status of shelters within the NTC.

Hypothesis generation

We conducted four hypothesis generating key informant interviews (KIIs) with the District Health Officer (DHO), Chairperson Kisoro District Local Government, District Surveillance Focal person (DSFP), NTC Camp commandant, and Medical Teams International (MTI)’s clinical lead officer. We also interviewed nineteen case-patients in the COVID-19 isolation unit. We explored factors related to non-adherence to preventive measures.

Unmatched case control study

We conducted an unmatched case control study with refugees after verbal informed consent. We defined a case as a person who had a negative COVID-19 test at entry and positive COVID-19 test at exit and had stayed ≥5 days at NTC between June 26 and July 16, 2022. A control was defined as person who had a negative COVID-19 test at both entry and exit and had stayed ≥5 days at NTC between June 26 and July 16, 2022. The outcome variable was COVID-19 positive at exit (for a case) and COVID-19 negative test at exit (for a control) given a negative COVID-19 test at entry. For each case and control, we collected data on: age, sex, education level, moving out of the centre, frequency of moving out of the centre, interaction with host community, having COVID-19 symptoms at time of COVID -19 test at exit, cigarette smoking, chronic medical illness, possession of face mask, hand washing, COVID-19 vaccination before entry to the center, date of last COVID-19 vaccination before entry to the center.

We collected data using an electronic tool in kobocollect. and exported to epi info version 7.2.5.0 for analysis. We used logistic regression to identify factors associated with COVID-19 infection. Variables that had a p-value <0.2 at bivariate analysis were included in the final model for multivariate analysis in a backward stepwise approach. Corresponding adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals were reported. The final level of significance was considered at a p-value <0.05.

Ethical considerations and consent to participate

COVID-19 in Uganda was declared a public health emergency and the Uganda Ministry of Health (MoH) gave the directive to investigate the COVID-19 outbreak in NTC upon request from Kisoro District Local Government. We also sought administrative clearance to conduct the from Kisoro District Local Government and the NTC camp commandant. The Office of Science, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, also determined that this activity was conducted in response to a public health emergency, with the primary intent of public health practice (epidemic disease control activity), hence it was determined not to be human subjects research. At the time of conducting this investigation, the MoH Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for COVID19 infection control discouraged the exchange of materials by hand. We therefore obtained verbal informed consent from eligible participants before data collection. During data collection, respondents were assigned unique identifiers instead of names to protect their confidentiality. Information was stored in password-protected computers and was not shared with anyone outside the investigation team.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

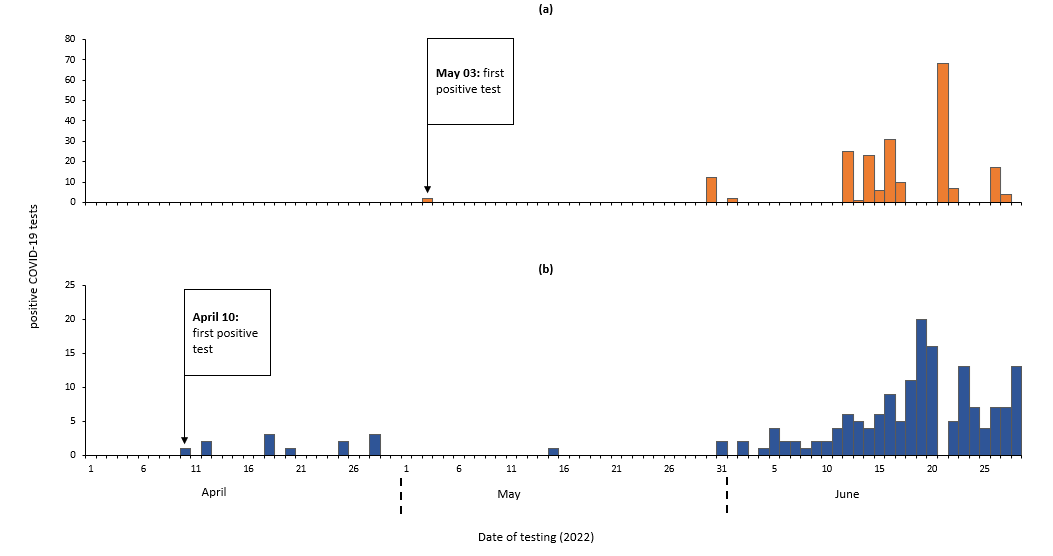

We identified 380 confirmed case-persons and no death. Of these 206 (54.2%) were male. The mean age was 19.3 years (SD±12.6). The first positive test among new arrivals was registered on April 10, 2022 and among relocations on May 03, 2022 (Figure 3).

Environmental assessment findings

We observed crowding among refugees, especially at the screening area on arrival, within the shelters, and during the lining up for food and relief items. This was similar to what was reported in the key informant interviews that revealed that shelters were at twice their capacity and the isolation unit was at three times its capacity.

Hypothesis generation interview findings

Key informant interviews

Key informant interviews revealed that the number of refugees were beyond the holding capacity of the NTC, most of refugees did not use face masks despite each being given a mask at entry, and that refugees had other bothering concerns like safety, family, food, among others than the concern of catching COVID-19 as highlighted in the following quotes………….“This is overwhelming… as we speak now… the shelters have 1,600 individuals yet they have a total capacity of eight hundred twenty-five…the isolation unit that we set up for twenty-five patients…. sometimes can have sixty-five patients…” Nyakabande transit centre commandant

We also observed minimal use of facemasks among refugees in Nyakabande transit centre even among the case patients in COVID-19 isolation unit. Among those observed using facemasks, most of them used the facemasks incorrectly. Finding in the key informant interviews also agreed to our observations

“we give every refugee one cloth facemask… but most of them do not use their facemasks…” Nyakabande transit centre clinical lead

It was also reported that most refugees were concerned about the safety of their lives, property, family and what to eat including the concern about their conjugal rights. It was thought that they could have been prioritizing these over the COVID-19 control measures.

“When refugees come here to the transit centre… they still think they are not safe… they think of danger any time… worry about their property and family… what to eat… I have heard many complaining that they can’t have their conjugal rights…” Chairperson Kisoro District Local Government

Structured interviews with the COVID19 patients at the isolation units

Out of the 19 case-patients interviewed, 6(32%) did not wear face masks at all, 3(16%) reported close interaction with a symptomatic person before developing the illness.

Based on the descriptive epidemiology and the hypothesis generation interview findings, we hypothesized that crowding and non-compliance to personal protective measures was associated with an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 at NTC.

Case control findings

In a case control study, we enrolled 42 cases and 127 controls. The cases were comparable to controls across age, sex, and level of education. Thirty-three (78.6%) of the cases were aged between 5-29 years. Thirty-four (89.5%) of cases had neither attended school nor completed primary education (Table 1).

Table 1:Socio-demographic characteristics of cases and controls in Nyakabande Transit Centre, Kisoro District, Uganda, June-July 2022

| Variable | Cases (N=42) | Controls (N=127) | P-value | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex

Male Female |

21 21 |

50.0 50.0 |

57 70 |

44.9 55.1 |

0.56 |

| Age ð

5-29 30-49 ≥50 |

33 6 3 |

78.6 14.3 7.1 |

94 26 7 |

74.0 20.5 5.5 |

0.69 |

| Education level

None or Primary Secondary or Tertiary |

34 4 |

89.5 10.5 |

62 18 |

77.5 22.5 |

0.14 |

Að Median age is 24 (Range, 21-29) years for both cases and controls

In the multivariate analysis, using a facemask most of the time (aOR=0.06, 95% CI 0.02-0.16) reduced the odds of infection by 94%. The odds of contracting COVID-19 infection among refugees who had close contact with a COVID-19 symptomatic person were (aOR=10.34, 95%CI 3.29-32.55) (Table 4).

Table 4: Factors associated with COVID-19 infection among refugees in Nyakabande Transit Centre, Kisoro District, Southwestern Uganda, June-July 2022

| Variable | cOR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) |

| Sex

Male Female |

Ref 1.23 |

(0.61-2.47) |

||

| Age

5-29 30-49 ≥50 |

Ref. 0.66 1.22 |

(0.25-1.74) (0.30-5.00) |

Ref. 0.94 3.38 |

(0.29-2.97) (0.57-20.07) |

| Education level

None or Primary Secondary or Tertiary |

Ref. 2.47 |

(0.73-10.8) |

Ref. 1.07 |

(0.28-4.07) |

| Shelter location

Transit Centre Holding Centre |

Ref. 0.95 |

(0.47-1.95) |

||

| Moving out of the center

Moves out Does not move out |

Ref. 0.51 |

(0.23-1.12) |

Ref. 2.49 |

(0.86-7.25) |

| Frequency of moving out in a week

Once More than once |

Ref. 0.56 |

(0.23-1.36) |

||

| Interact with the host community

No Yes |

Ref. 1.2 |

(0.52-2.81) |

||

| Cigarette smoking

No Yes |

Ref. 4.28 |

(0.59- 87.28) |

Ref. 0.52 |

(0.05-4.91) |

| Close contact with a COVID-19 symptomatic person

No Yes |

Ref. 0.27 |

(0.12-0.60) |

Ref. 10.34 |

(3.29-32.55) |

| Having a family member with COVID-19 in NTC seven days before the exit test

No Yes |

Ref. 1.90 |

(0.40-8.93) |

||

| Using facemask

No Yes |

Ref. 9.63 |

(4.36-21.25) |

Ref. 0.06 |

(0.02-0.16) |

| Frequency of use of a facemask

Rarely or never Specific occasions Most of the time |

Ref. 0.11 0.05 |

(0.01-1.60) (0.004-0.59) |

||

| COVID-19 vaccination before entry

No Yes |

Ref. 1.22 |

(0.23-6.53) |

cOR: Crude Odds Ratio; aOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval; Ref: Reference category; NTC: Nyakabande Transit Centre

Discussion

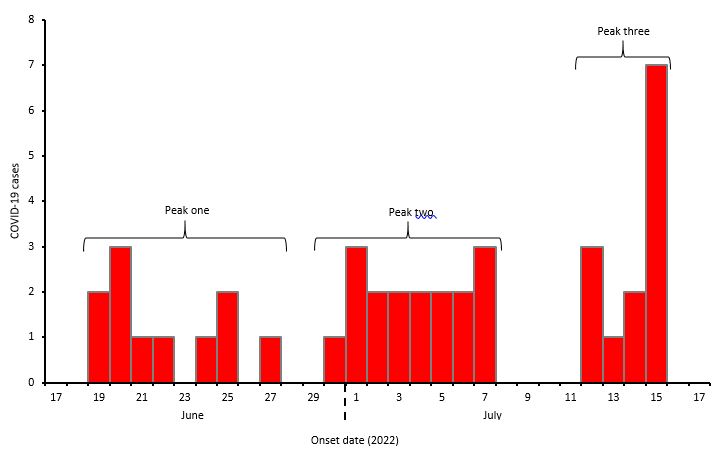

The investigation showed that the COVID-19 positivity rate at the exit was six times higher than that at the entry to NTC suggesting COVID-19 transmission within NTC. The epidemic curve had three successive with one incubation period apart suggesting a propagated epidemic. Having close contact with a symptomatic person increased the odds of COVID-19 infection. Overcrowding and failure to use facemasks among refugees likely fueled the outbreak.

Close contact with a symptomatic person increased the odds of COVID-19 infection in this outbreak. COVID-19 virus is transmitted through droplets, and aerosols (1, 18). This especially happens when someone comes in close contact with an infected person (19-22). The crowding observed in the transit could have facilitated the close contact among refugees. Overcrowding has been reported as a risk factor for COVID-19 infection among refugees. A study conducted in refugee camps in Bangladesh found higher prevalence of COVID-19 in overcrowded camps(23). Another study in Jordan found that overcrowding was a risk factor for COVID-19 infection among Syrian refugees living in urban areas(24). Expanding shelter space and enforcing social distance especially at the time of distribution of food and other essential items to refugees could minimize close contact among refugees.

Facemasks protect against COVID-19 infection by limiting the movement of infectious droplets(1, 25). Because of this, during the COVID-19 pandemic, face masks were made mandatory for use in public (26-29). Our study results corroborate the notion that consistently wearing face masks significantly decreases the likelihood of COVID-19 infection among refugees, with odds reduction exceeding 90%. Most refugees did not wear the cloth masks they were given, even though this could have reduced their risk of COVID-19 infection. This was likely due to the challenging conditions they faced as refugees, which made them more worried about other problems, such as safety, food, and shelter. When they had to queue for essential items like food, the situation became even more difficult. A study conducted in a refugee camp in Bangladesh found that most refugees did not consistently use face masks even when provided with one, and this contributed to the higher prevalence of COVID-19 in the camp(30). Similarly, a study in Jordan identified overcrowding and lack of access to basic amenities as major risk factors for COVID-19 infection among Syrian refugees living in urban areas, and that the use of face masks significantly reduced the risk of transmission (24).

The investigation had the following limitations. Firstly, refugees who met the case definition and were transferred to resettlement camps were not followed up because of logistical limitations to reach the settlements they had been settled, potentially resulting in underestimation of the study outcomes. Secondly, incomplete records on sex, and age of refugees in the registers at the NTC may have resulted in an underestimation of disease burden. Lastly, the retrospective nature of the investigation is susceptible to recall and social desirability bias, as participants may have been inclined to provide answers that were considered appropriate. This could have resulted into an overestimation of the effect of the associated factors on the COVID-19 infection.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the COVID-19 outbreak at NTC was facilitated by overcrowding and failure to use personal protective measures. Enforcing face mask use and expanding shelter space at NTC could reduce the risk of future outbreaks.

Public health actions

Following the dissemination of our findings, a health sensitization program focused on educating refugees about the use of facemasks was organized in collaboration with the clinical lead at the NTC. The training emphasized the risks of COVID-19 infection, the correct way to wear a facemask, and the benefits of using facemasks to protect one’s own health and that of others in the community. We observed a positive change in facemask usage behavior among refugees, and those who did not have facemasks before began to request for them. We recommend that this health talk on facemask usage be continued on a daily basis.

We organized advocacy meetings with the NTC camp management and Kisoro District Local Government to discuss the urgent need for expanding shelter space and increasing the procurement and distribution of facemasks. Our goal was to ensure that every refugee had access to at least two facemasks. The leadership was responsive to our proposal and mobilized implementing partners to procure more facemasks. Furthermore, the NTC management prioritized the expansion of shelter space as an intermediate-term action to be taken.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Health for permitting us to respond to this outbreak. We thank the Kisoro district local government and the management of NTC for granting permission and overall guidance to the team.

Copyright and licensing

All material in the Uganda National Institute of Public Health Quarterly Epidemiological Bulletin is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission. However, citation as to source is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- WHO WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) 2022 [Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1.

- Orendain DJA, Djalante R. Ignored and invisible: internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the face of COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability science. 2021;16(1):337-40.

- Lau LS, Samari G, Moresky RT, Casey SE, Kachur SP, Roberts LF, et al. COVID-19 in humanitarian settings and lessons learned from past epidemics. Nature Medicine. 2020;26(5):647-8.

- UNHCR TURA-A. 2021. [cited 2022]. Available from: https://www.unhcr.org/health-covid-19.html.

- Hargreaves S, Kumar BN, McKee M, Jones L, Veizis A. Europe’s migrant containment policies threaten the response to covid-19. British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2020.

- Malteser International OoMwr. Keeping refugee camps free from the coronavirus pandemic 2022 [cited 2022 11/12/2022]. Available from: https://www.malteser-international.org/en/current-issues/refugees-and-displacement/coronavirus-in-refugee-camps.html.

- Zard M, Lau LS, Bowser DM, Fouad FM, Lucumí DI, Samari G, et al. Leave no one behind: ensuring access to COVID-19 vaccines for refugee and displaced populations. Nature Medicine. 2021;27(5):747-9.

- Benos A, Kondilis E, Pantoularis I, Makridou E, Rotulo A, Seretis S. Critical Assessment of Preparedness and Policy Responses to SARS-CoV2 Pandemic: International and Greek Experience. CEHP-Centre for Research and Education in Public Health, Health Policy and …; 2020.

- International M. Keeping refugee camps free from the coronavirus pandemic 2020 [Available from: https://www.malteser-international.org/en/current-issues/refugees-and-displacement/coronavirus-in-refugee-camps.html#:~:text=Millions%20of%20refugees%20and%20displaced,camps%20would%20have%20devastating%20consequences.

- Martuscelli PN. How are forcibly displaced people affected by the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak? Evidence from Brazil. American Behavioral Scientist. 2021;65(10):1342-64.

- Abbas Kigozi CG. Access to COVID-19 vaccines for refugees in Uganda 2022 [cited 2022 11/12/2022]. Available from: https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/access-covid-19-vaccines-refugees-uganda.

- Control CfD, Prevention. Interim guidance on management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in correctional and detention facilities. 2021.

- Malchrzak W, Babicki M, Pokorna-Kałwak D, Doniec Z, Mastalerz-Migas A. COVID-19 Vaccination and Ukrainian Refugees in Poland during Russian–Ukrainian War—Narrative Review. Vaccines. 2022;10(6):955.

- Alio M, Alrihawi S, Milner J, Noor A, Wazefadost N, Zigashane P. By refugees, for refugees: Refugee leadership during COVID-19, and beyond. International Journal of Refugee Law. 2020;32(2):370-3.

- UNHCR TURA. Global Trends Report 2021. 2021.

- UNHCR TURA. Thousands flee into Uganda following clashes in DR Congo. 2022.

- UNHCR TURA. Uganda Refugee Settlements: COVID-19 update 2022 [Available from: https://data.unhcr.org/es/dataviz/153.

- Lotfi M, Hamblin MR, Rezaei N. COVID-19: Transmission, prevention, and potential therapeutic opportunities. Clinica chimica acta. 2020;508:254-66.

- Xia W, Shao J, Guo Y, Peng X, Li Z, Hu D. Clinical and CT features in pediatric patients with COVID‐19 infection: different points from adults. Pediatric pulmonology. 2020;55(5):1169-74.

- Tian S, Hu N, Lou J, Chen K, Kang X, Xiang Z, et al. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. Journal of infection. 2020;80(4):401-6.

- Spagnuolo G, De Vito D, Rengo S, Tatullo M. COVID-19 outbreak: an overview on dentistry. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(6):2094.

- Chen Y, Wang A, Yi B, Ding K, Wang H, Wang J, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of infection in COVID-19 close contacts in Ningbo city. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2020;41(5):667-71.

- Islam MS, Rahman KM, Sun Y, Qureshi MO, Abdi I, Chughtai AA, et al. Current knowledge of COVID-19 and infection prevention and control strategies in healthcare settings: A global analysis. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2020;41(10):1196-206.

- Doocy S, Lyles E, Akhu-Zaheya L, Burton A, Burnham G. Health service access and utilization among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):108.

- CDC CoDCaP. COVID-19, What’s New & Updated 2022 [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/whats-new-all.html.

- Karmacharya M, Kumar S, Gulenko O, Cho Y-K. Advances in facemasks during the COVID-19 pandemic era. ACS Applied Bio Materials. 2021;4(5):3891-908.

- Howard J, Huang A, Li Z, Tufekci Z, Zdimal V, van der Westhuizen H-M, et al. An evidence review of face masks against COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021;118(4):e2014564118.

- Greenhalgh T, Schmid MB, Czypionka T, Bassler D, Gruer L. Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. Bmj. 2020;369.

- Garcia LP. Use of facemasks to limit COVID-19 transmission. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde. 2020;29.

- Ahmed F, Ahmed Ne, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e240.