Measles outbreak at a refugee settlement, Kiryandongo District, Uganda, July–October 2023

Authors: Edith Namulondo1*, Innocent Ssemanda1, Mariam Komugisha1, Yasin Nuwamanya1, Susan Wako1, Edirisa Junior Nsubuga,2, Joshua Kayiwa2, Richard Akuguzibwe3, Benon Kwesiga1, Richard Migisha1, Alex Riolexus Ario1; Institutional Affiliations:1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Kampala, Uganda, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda1; 2Public Health Emergency Operations centre, Ministry of Health Uganda, 3Kiryandongo District Local Government, Kiryandongo, Uganda; *Correspondence: Tel: +256772616245, Eamil: enamulondo@uniph.go.ug

Summary

Introduction: Measles is a highly infectious viral disease that mostly affects children. On 28 August 2023, the Ministry of Health was notified of an outbreak of measles in Kiryandongo, a refugee hosting district located in Western Uganda. We investigated to determine the scope of the outbreak, factors associated with transmission, vaccine effectiveness and coverage, and recommend evidence-based interventions.

Method: We defined a suspected case as onset of fever (lasting ≥3 days) and maculopapular rash with ≥1 of: cough, coryza or conjunctivitis in a resident of Kiryandongo District from July 1–October 25, 2023. A confirmed case was a suspected case with positive measles-specific IgM not explained by vaccination in the past 8 weeks. Cases were identified through medical records review and active case search. We conducted a descriptive analysis and an unmatched case-control study (1:2) to evaluate risk factors for transmission during the case-person’s exposure period (7–21 days prior to rash onset). We estimated vaccine effectiveness (VE) as VE≈100 (1-ORprotective), using the odds ratio associated with having received ≥1 dose of measles vaccine. We calculated vaccination coverage using the percent of eligible controls vaccinated. We also carried out interviews with key settlement staff.

Results: We identified 74 case-patients (14 confirmed), 54% were females and non-died. The overall attack rate (AR) was 16/100,000 population and was higher among refugees than among nationals (49 vs 11/100,000). Children <12 months (AR=108/100,000) were the most affected age group. Being vaccinated (AOR=0.13, 95%CI: 0.06-0.31) and playing around a water collection point (AOR=3.2, 95%CI: 1.4-6.9) were associated with infection. Vaccination coverage was 87% among refugees and 85% among nationals; VE was 87% (95% CI=69-94) for both groups. Interviews with key staff revealed unrestricted movement of unregistered refugees visiting their relatives in and out of the settlement.

Conclusion: The measles outbreak was associated with suboptimal vaccination coverage and unrestricted movement of persons into and out of the settlement. Increased screening of persons entering the settlement and strengthened immunization programs could avert a similar situation in the future.

Introduction

Measles is a highly infectious viral disease that can cause severe complications and death, especially among children under five years of age. It’s transmitted through respiratory droplets from infected persons and can spread rapidly in susceptible populations [1]. Measles can be prevented by vaccination, which is safe and effective [1, 2]. However, measles remains a major public health problem in many parts of the world, particularly in resource-limited settings where vaccination coverage is low, and outbreaks are frequent[3].

Globally, epidemics of measles cause an estimated 2.6 million deaths each year. Measles and rubella remain a major cause of worldwide morbidity and mortality with an estimated 7.5 million measles cases and more than 60,700 measles-related deaths in 2020[4]. According to the World health organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the estimated coverage of the first dose of measles-containing vaccine, meaning that more than 22 million children did not receive their first dose in 2020. Global coverage of the second dose also declined in 2020 to 70%, from 71% in 2019[5]. WHO and CDC reported that due to ongoing declines in measles vaccination, cases in 2022 rose by 18%, and deaths were up 43% globally compared to 2021. Thirty-seven countries reported large or disruptive outbreaks in 2022, up from 22 in 2021 and African region was hit hardest, with 28 outbreaks 6 in the Eastern Mediterranean, 2 in Southeast Asia, and 1 in the European Region[6].

Uganda is one of the countries in the African region that has experienced recurrent measles outbreaks in recent years [7, 8]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Uganda reported 1,039 confirmed measles cases and 12 deaths in 2021, with a case fatality rate of 1.2%. Most of the cases occurred among children under five years of age, who accounted for 72% of the total cases and 83% of the deaths [9]. The outbreaks were attributed to low routine immunization coverage, inadequate surveillance, and delayed outbreak response.

In 2023, Uganda launched a nationwide measles-rubella vaccination campaign, targeting 18.1 million children aged 9 months to 15 years, with the aim of achieving at least 95% coverage in each district. The campaign was conducted in two phases, from 12–16 September and from 19–23 September, using a fixed-post and outreach strategy [10]. The campaign also included vitamin A supplementation and deworming for children under five years of age.

On 28 September 2023, the Ministry of Health (MoH) declared a measles outbreak in Kiryandongo District, Western Uganda following a 6 cases laboratory confirmed by the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI). We investigated the outbreak to determine its scope, Identify the risk factors for transmission, and recommendations evidence-based control and prevention measures.

Methods

Outbreak area

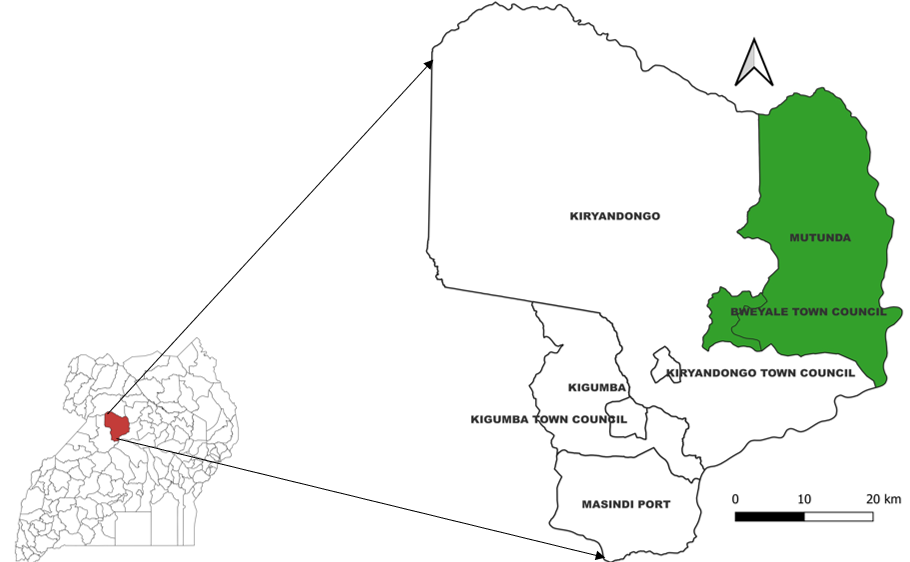

We conducted the investigation in Kiryandongo District in Bunyoro sub-region, which is located in the western part of Uganda (Figure 1). The district has seven sub-counties (three town councils and four sub-counties). Mutunda subcounty and Bweyale Town Council (in green) host the refugee population (Figure 1). Mutunda subcounty has 2 health facilities: Mutunda Health Centre III and Panyadoli Health Centre III, while Bweyale Town Council has 3 health facilities: Kichwabugingo Health Centre II, Nyakadoti Health Centre III and Panyadoli Health Centre IV which is the referral facility for the settlement. All these 5 facilities offer immunization services at static and outreach levels. The estimated population is 171,095 for Bweyale TC and 86732 for Mutunda SC out of which 59,200 are refugees.

Case definition and finding

We defined a suspected case as onset of fever lasting ≥3 days and maculopapular rash with ≥1 of: cough, coryza or conjunctivitis in a resident of Kiryandongo District from July 1–October 25, 2023. A confirmed case was a suspected case with positive measles-specific IgM test.

We line-listed suspected measles cases by reviewing medical records in all the 5 health facilities serving the refugee settlement population. We searched for additional cases in the community by asking members of households with suspected cases to direct us to other households with children of similar measles-like symptoms. We used a standardized case investigation form to collect data on case-patients’ demographics, clinical information, vaccination status and exposure history.

Laboratory investigations

Samples were collected from suspected case-patients and sent to UVRI for testing.

Descriptive epidemiology

We constructed an epidemic curve to assess the time distribution of measles cases. We computed the attack rates by person and place using the Uganda Bureau of statistics projected populations of children [11] as the denominator and presented results using graphs and tables.

Hypothesis generation

We collected information from a random sample of 20 suspected case-patients using a measles case investigation form. We asked case-patients’ caretakers about potential risk factors for measles transmission occurring between 7 and 21 days prior to symptom onset. The risk factors included: not being vaccinated, attending a place of worship, visiting a health facility, visiting a water collection point and visiting or receiving a visitor from outside the district. Evidence of vaccination included child health cards or, if missing, caretakers’ recall, which we attempted to confirm by asking the site and age at which the child received the measles vaccine. We generated hypotheses about exposures based on findings from the descriptive epidemiology analysis and hypothesis-generation interviews. To further support our hypothesis, we carried out interviews with key informants from the refugee settlement.

Case control investigation

We conducted an unmatched case control investigation in the refugee settlement to test our hypotheses. We defined a control as a resident of Kiryandongo refugee settlement aged 6 months–6 years (all cases were in the same range) with no history of fever or rash from 1st July–25th October 2023. Cases and controls were selected in the ratio of 1:2, with one additional control identified. The controls were selected using simple random sampling from non-case households in the same neighborhood as cases. All eligible children from the selected household were listed down and a random number selected. Data was analyzed using Epi Info 7.1.5 version. To assess factors associated with measles infection, we obtained adjusted Mantel-Haenszel odds ratios (ORMH) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs)

Vaccination coverage (VC)

We estimated the one dose VC using the percent of eligible controls vaccinated.

Vaccination effectiveness (VE)

We calculated VE using the formula: VE≈100 (1-ORprotective), using the odds ratio associated with having received one dose of measles vaccine.

Ethical consideration

We conducted this study in response to a public health emergency and as such was determined to be non-research. The MoH authorized this study and the office of the Center for Global Health, US Center for Diseases Control and Prevention determined that this activity was not human subject research and with its primary intent being for public health practice or disease control. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. We obtained permission to conduct the investigation from the district health authorities of Kiryandongo. We obtained written informed consent from all the respondents. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary and that there would be no negative consequences for declining or withdrawing from the study (none declined or withdrew). Data collected did not contain any individual personal identifiers and information was stored in password-protected computers, which were inaccessible by anyone outside the investigation team.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology

We identified 74 case-patients (60 suspected and 14 confirmed) with an overall attack rate [AR] of 16/100,000. There were no deaths and Females were 40 (54%). The AR was higher among the refugees than among nationals (49 vs 11/100,000). The most affected subcounty was Mutunda (AR=102/1000,000), followed by Bweyale Town Council (AR=65/100,000), Kiryandongo town council (AR=11/100,000), and Kiryandongo subcounty (AR=10/100,000). The age range of the case-patients was 4 months to 6 years. The most affected age group was 7-11 months (AR=183/100,000), followed by 1-4 years (AR=59/100,000), 0-6 months (AR=47/100,000) (Table 1). The attack rate was similar among females (17/100,000) and males (16/100,000). All (100%) cases presented with fever and generalized rash; 42 (84%) had cold, 41(82%) had cough, and 29(58%) had conjunctivitis.

Table 1: Measles attack rates by the subcounty of residence, age group, and sex during a measles outbreak in the refugee settlement, Kiryandongo District, Uganda, July–October 2022

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Population | Attack rate/100,000 |

| Sub-county | Mutunda | 31 | 30,356 | 102 |

| Bweyale TC | 39 | 59,883 | 65 | |

| Kiryandongo TC | 2 | 17,527 | 11 | |

| Kiryandongo | 2 | 20,906 | 10 | |

| Age-group | 0-6 months | 5 | 10,745 | 47 |

| 7-11 months | 16 | 8,750 | 183 | |

| 1-4 years | 43 | 73,445 | 59 | |

| 5-14 years | 10 | 150,064 | 7 | |

| >15 years | 0 | 210,362 | 0 | |

| Sex | Male | 34 | 217,615 | 16 |

| Female | 40 | 235,750 | 17 |

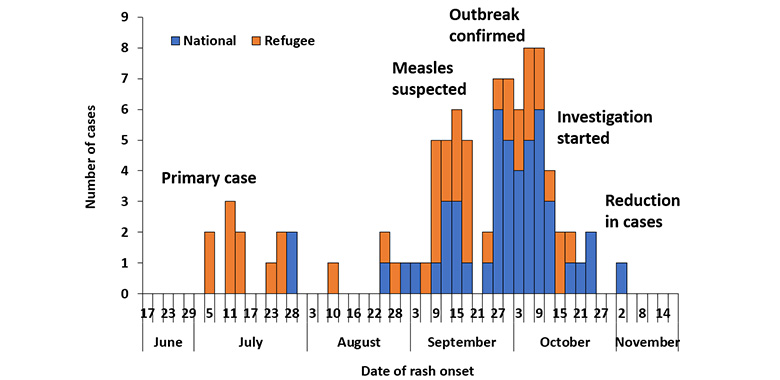

The epidemic curve (Figure 2) showed a propagated measles outbreak lasting approximately 150 days. The primary case was identified on 3 July 2023, a refugee child with no history of measles vaccination from Bweyale town council. The outbreak was not suspected until 11 September 2023, when health workers in Panyadoli HC IV (serving the refugee settlement population) started seeing children presenting with measles like symptoms. The outbreak was confirmed on 28 August 2023 and Investigations started on 11 October 2023.

Hypothesis generation findings

Of the 20 case-patients interviewed, 15 (75%) had visited a place of worship, 13(65%) were not vaccinated, 11 (55%) had played round a water collection point during the exposure period, 6 (30%) visited a health facility, 3 (15%) had gone to school, and 1 (5%) had received a visitor from outside the district. No other exposures were reported. We considered all exposures that were reported by at least 2 case-patients as potential exposures to include in the case-control study. We therefore considered going to a place of worship, not being vaccinated and playing around a water collection point as possible factors associated with the outbreak.

Interviews with key informants from the refugee settlement revealed that: Incoming refugees were not screened to assess vaccination status, the unregistered refugees feared taking children for immunization and there was unrestricted movement of refugees into and out of the settlement and it was worth noting that most refugees were from South Sudan that had suffered from measles outbreak for the past one year.

Case control investigation findings

Twenty-nine (58%) case-patients and 27 (26%) control-persons played around at a water collection point (ORMH=3.2, 95% CI: 1.4-6.9). Thirty-eight (76%) case-patients and 60 (59%) control-persons visited a place of worship (ORMH=1.0, 95% CI: 0.43-2.4) (Table 2).

Table 2: Factors associated with measles transmission during the measles outbreak in the refugee settlement, Kiryandongo District, Uganda, July–October 2022

| Risk factor | Cases

N (%) |

Controls

n (%) |

ORMH | (95% CI) | ||

| Received measles vaccination | 17 | (34) | 81 | (80) | 0.13 | (0.06-0.31) |

| Playing around a water collection point | 29 | (58) | 27 | (26) | 3.2 | (1.4-6.9) |

| Visiting a place of worship | 38 | (76) | 60 | (59) | 1.0 | (0.43-2.4) |

Measles vaccine coverage and vaccine effectiveness

Among control-persons aged ≥6 months to 6 years, we estimated the overall vaccination coverage to be 86% (95% CI: 76-94%). It was similar among refugees 87% (95% CI: 73-94%) and nationals 85% (95% CI: 76-91%). Seventeen (34%) case-patients and 81 (80%) control-persons had received a dose of measles vaccination (ORMH=0.13, 95% CI: 0.06-0.31), giving an estimated VE of 87% (95% CI: 69–93%).

Discussion

This outbreak in the refugee settlement area (Mutunda Subcounty and Bweyale Town-council) represented the second measles outbreak in the same year, 2023. Vaccination was associated with reduced odds of infection. The estimated vaccine effectiveness for a single dose lies in the expected range of 89-95% [9]. Overall, the estimated measles vaccination coverage was below 95% and was similar when stratified by nationality and refugees. The outbreak was propagated by children congregating at community water collection points. The sub-optimal vaccination coverage of a single measles vaccine dose increased community susceptibility to infection since it doesn’t build herd immunity to the community.

A history of measles vaccination was protective in this outbreak. However, attack rates were three times as high in children aged 7-11 months as children aged 1-4 years. This may be due to sub-optimal vaccination coverage of children in the settlement area. While school going children may also have more opportunities for exposure, this outbreak affected children of age group 4months -6 years of which only 18% were attending school and thus this was not a factor in this outbreak. The comparatively lower protection offered by a single dose of the measles vaccine led to the recommendation by WHO to add a second dose of measles vaccine into the routine vaccination schedule [9].

Socializing of children at water collection points was associated with increased odds of infection. Other studies have also identified socialization as a factor that facilitates measles transmission [11]. In rural Uganda, water collection points are typically areas where young children play with each other while they wait for their mothers or older siblings to collect water for domestic use. If a child at a water collection point is ill, other children can be put at risk of contracting infection.

The lack of severe illness or deaths among patients in this study may also be reflected in the relatively high vaccination rates; studies have shown that when measles occurs in immunized individuals, the illness is less severe [11].

Study limitations

In this investigation, we assumed that the controls were representative of the general population and used the proportion of controls vaccinated to estimate vaccination coverage instead of the standard WHO community survey method. Vaccination status was in some cases based on caretakers’ recall, which might have led to recall bias leading to an overestimation or underestimation of vaccine effectiveness and vaccination coverage. This might have overestimated the vaccination coverage. Finally, we also could not triangulate the administrative measles vaccination coverage with the estimated measles vaccination coverage (proportion of controls vaccinated) used to calculate vaccination coverage in this study since vaccination records in some of the health facilities were not up to date. This likely resulted in a low records-based administrative coverage of 79% compared to the calculated vaccination coverage of 86%.

Conclusion

Socializing at water collection points was associated with this measles outbreak. Measles vaccination was protective against measles infection. We recommended that the Kiryandongo District Health team conduct a mass community measles vaccination (or re-vaccination) campaign for all children in the refugee settlement to capture unvaccinated children in the area and provide a second dose for those who might have received one dose. Children who had not received the measles vaccines were referred to the nearby health facilities, where they received their vaccines.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest.

Authors contribution

EN: participated in the conception, design, analysis, interpretation of the study and wrote the draft bulletin; IS, MK, YN, BK, EJN, SW, JK, RA reviewed the report, reviewed the drafts of the bulletin for intellectual content and made multiple edits to the draft bulletin; BK, RM, DK, and ARA reviewed the bulletin to ensure intellectual content and scientific integrity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Kiryandongo District health office and the management of Kiryandongo refugee settlement for the technical and administrative support rendered during the outbreak.

Copyrights and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- WHO. Measles. 2022; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles?gclid=Cj0KCQiAo7KqBhDhARIsAKhZ4uhRRwlWUgqRtkuu57MCaddsDyDK8TOAY9CDhgxa-usoiffyVR_CXOsaAv34EALw_wcB.

- Sbarra, A.N., et al., Estimating national-level measles case–fatality ratios in low-income and middle-income countries: an updated systematic review and modelling study. The Lancet Global Health, 2023. 11(4): p. e516-e524.

- Tariku, M.K., et al., Attack rate, case fatality rate and determinants of measles infection during a measles outbreak in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2023. 23(1): p. 756.

- Dixon, M.G., et al., Progress toward regional measles elimination—worldwide, 2000–2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2021. 70(45): p. 1563.

- Muhoza P, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Diallo MS, Murphy P, Sodha SV, Requejo JH, Wallace AS. Routine Vaccination Coverage – Worldwide, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Oct 29;70(43):1495-1500. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7043a1. Erratum in: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Nov 19;70(46):1620. PMID: 34710074; PMCID: PMC8553029.

- Measles cases and deaths are increasing worldwide, say WHO and CDC

BMJ 2023; 383 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p2733 (Published 20 November 2023) Cite this as: BMJ 2023;383:p2733.

- Namugga, B., et al., The immediate treatment outcomes and cost estimate for managing clinical measles in children admitted at Mulago Hospital: a retrospective cohort study. medRxiv, 2023: p. 2023.01. 04.23284186.

- Flavia, A., B. Fred, and T. Eleanor, Gaps in vaccine management practices during Vaccination outreach sessions in rural settings in southwestern Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2023. 23(1): p. 758.

- Kizito, S.N. 2023; Available from: https://uniph.go.ug/measles-outbreak-propagated-

by-visiting-a-health-facility-in-a-refugee-hosting-community-kiryandongo-district-western-uganda-august-2022-may-2023 #:~:text=In%202019%2C%20Uganda%20reported%209%2C774,cases%20occurring%

20in%20refugee%20settlements.&text=At%20the%20end%20of%20December,

from%20January%20to%20February%202023. - WHO. Statement from Uganda’s Minister of Health on the National Measles-Rubella and Polio Immunisation Campaign 2019. 2019; Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/news/statement-ugandas-minister-health-national-measles-rubella-and-polio-immunisation-campaign.

- UBOS, https://www.ubos.org/explore-statistics/20/. 2022.

Comments are closed.