Cross Border Population Movement Patterns, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, November 2022

Authors: Patrick King1*, Mercy Wendy Wanyana1, Brenda Nakafeero Simbwa1, Zalwango Gorreti Marrie1, Richard Migisha1, Daniel Kadobera1, Benon Kwesiga1, Lilian Bulage1, Doreen Gonahasa1, Peter B Ahabwe5, Harriet Mayinja2, Kobusinge Joyce Owens2, Harriet Itiakorit6, Serah Nchoko3, Edna Salat3, Freshia Weithaka3, Oscar Gunya3, Fredrick Odhiambo3, Mutabazi Vicent4, Habimana Metuschelah4, Ndabarinze Ezechiel4, Manishimwe Alexis4, Samuel Kedivani3, Twagirimana Gabriel4, Alex Ario1 Institutional affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, 2Ministry of Health, Division of Surveillance, Information and Knowledge Management, Kampala, Uganda, 3Kenya National Public Health Institute, Field epidemiology and Laboratory training Program, 4Ministry of Health Rwanda, Field epidemiology training program, 5Department of Global Health Security, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda, 6Department of Global Health Security, Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation, Kampala, Uganda *Correspondence*: Email: kingp@uniph.go.ug, Tel: +256775432193

Summary

Background: The frequent population movement across the five East African Countries poses a risk of disease spread across the region. A clear understanding of population movement patterns is critical for informing cross-border disease control interventions. We assessed population mobility patterns across the border for three East African member states (Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda).

Methods: In November 2022, we conducted focus group discussions, key informant interviews, and participatory mapping using Population Connectivity Across Borders toolkits. Participants were selected using purposive sampling and a topic guide used during interviews. Key informants included border districts (Uganda and Rwanda) and county health officials (Kenya). Focus group discussion participants were identified from border communities and travellers and these included truck drivers, commercial motorcyclists, and businessmen and women. During key informant interviews and focus group discussions, we conducted participatory mapping using Population Connectivity Across Borders toolkits. Data were analysed using grounded theory approach using Atlas ti 7 software.

Results: Different age groups travelled across borders for various reasons. Younger age groups travelled across the border for education, trade, social reasons, employment opportunities, agriculture and mining. While older age groups mainly travelled for healthcare and social reasons. Other common reasons for crossing the borders included religious and cultural reasons. Respondents reported seasonal variations in the volume of travellers. Respondents reported using both official (4 Kenya-Uganda, 5 Rwanda-Uganda borders) and unofficial Points of Entry (14 Kenya-Uganda, 20 Uganda-Rwanda) for exit and entry movements on borders. Unofficial points of entry were preferred because they had fewer restrictions like the absence of screening, and immigration and customs checks. Key destination points (points of interest) included: markets, health facilities, places of worship, education institutions, recreational facilities and business towns. Twenty-eight Health facilities (10- Lwakhakha, Uganda, 10- Lwakhakha, Kenya,8- Cyanika, Uganda) along the border were the most commonly visited by the travellers and border communities.

Conclusion: Complex population movement and connectivity patterns were identified along the border. These were used to guide cross-border disease surveillance and other border health strategies in the three countries. The findings were used to prioritise points of entry and points of interest for enhanced EVD exit and entry screening and preparedness activities during the September 2022 Sudan ebolavirus outbreak.

Background

The East African region is threatened by numerous emerging and re-emerging diseases of international concern. These include wild polio, yellow fever, Ebola Virus disease, Marburg Viral fever, Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever, Hepatitis E virus, and cholera(1). The spread of these diseases could be fuelled by the increased cross-border movements of humans and animals. This could increase the scope and magnitude of outbreaks further straining the health systems in the region(2).

Although data on population mobility patterns such as volume and destination are routinely collected at points of entry in the East African region, these are often insufficient for providing evidence for decision-making. The Population connectivity across borders (PopCAB) methodology provides detailed information on mobility patterns including the who, where, when, why, and how of human mobility and community connectivity(5). Furthermore, the methodology eases the integration of population mobility in public health surveillance, programming, preparedness, and response initiatives.

A clear understanding of the unique population movement patterns is essential for tailoring communicable disease preparedness and response strategies that aim to limit the international spread of disease. Characterisation of movement patterns including destinations, routes used, and reasons for travel could facilitate more accurate quantification of health risks, importing, and exporting disease(3,4). By considering the complex ways in which people move and interact with their environment, public health officials can design more effective preparedness and response strategies.

The Uganda Ministry of Health together with the respective ministries in Kenya and Rwanda conducted a PopCAB activity on the Uganda-Kenya Lwakhakha border and the Uganda-Rwanda Cyanika border to understand population movement patterns, identify points interest and travel routes, visualise population movement patterns, and suggest suitable public health recommendations for surveillance and preparedness in order to strengthen tailored interventions to prevent, detect, and respond to the spread of communicable diseases including the on-going Ebola Virus Disease outbreak at the time of the assessment.

Methods

We conducted the assessment at the Lwakhakha border (Uganda-Kenya border) and the Cyanika border (Uganda-Rwanda border). The Lwakhakha border is located the border of Namisindwa District in Uganda and Bungoma County in Kenya. The Cyanika border is located at the border of Kisoro District in Uganda and Burera District in Rwanda.

We used the POPCAB methodology toolkit developed by US Centre for Disease Control to gather and analyse population mobility including characteristics of travellers, reasons for travel routes taken by travellers, travel routes, and key destinations/points of interest.

Using an interview guide, we conducted KIIs with border district (Uganda and Rwanda) and county officials (Kenya) on the characteristics of travellers, reasons for crossing the borders, when they cross and means used for travel/cross the border. The KII interview findings generated information utilized in the selection of categories of people to be considered for the FGDs at the borders. Using an interview guide, we conducted FGDs with border communities and travellers and these included truck drivers, boda-boda riders, commercial cyclists, and business men and women.

All KIIs and FGDs had a participatory mapping component using maps for Uganda-Kenya border and Uganda-Rwanda border. Areas of interest and routes were annotated on the maps by the interviewer with guidance from the participants.

Discussions were transcribed by a note taker during the interview and analysis was later conducted using a thematic analysis approach. We developed codes and grouped codes under sub-themes and themes annotated maps from the various interviews were summarised into one (1) maps for each border point (Cyanika and Lwakhakha borders) to provide a comprehensive picture of the routes and points of entry used. We used QGIS software to draw maps.

Results

Characteristics of travellers

Respondents reported that mainly individuals below 35 years frequently cross the border. There were differences in the age groups travelling depending on the reason for travel. Both genders travelled across the border. Unique to the Lwakhakha border, respondents in Uganda reported both genders crossing the border while Kenyan respondents reported mostly males crossing the border. Nationalities in the East African region (Ugandan, Kenyan, South Sudanese, Congolese, and Rwandese) commonly travelled across the borders.

“……Youth and young adults are the most common people moving across both countries……usually men aged 15-30 year and women aged 14-20 year mainly travel for employment opportunities” FDG P4, boda-boda Uganda

“…. It depends on the activity, children from 6 years to 15 years from Uganda move to Kenya selling snacks and fruits/vegetables….. from 15 years to 30 Ugandans move from Mbarara, Mbale and Namisindwa for casual labour as maids…. adults above 20 to 35 years move for casual labour on farms in Eldoret, Chwele while others move to Nairobi, Eldoret, Chwele to work as maids” FDG, P7 boda-boda Kenya.

“…. Sudan refugees cross weekly and monthly…” FGD P1, Uganda.

“…… Ugandans and Rwandese with some Congolese crossing Cyanika border as a connecting route to Gisenyi and Goma “……FDG P11, Uganda

Reasons for travel

Livelihood

Respondents reported trade in various items including food, livestock and household items across the border. They cited cheaper goods on the other side of the border as a motivation to travel to various markets across the border. In all three countries respondents reported travelling in search of employment opportunities, mainly casual work on the other side of the border. Unique to the Cyanika border, communities travelled from Rwanda for mining activities in Uganda. Commercial sex and smuggling were also reported as reasons for travel

“…People travel to Kisoro market on the side of Uganda and Musanze Market on the side of Rwanda to buy and sell different things…” Participant 5 FDG Cyanika

“.….People cross the border for business. They come and buy farm produce like bananas in markets in Bududa District(Uganda). Others go to Kampala and Jinja to buy items like clothes, shoes etc… some smuggle goods across the border….” Participant 5 FDG Lwakhakha

“…. travelers move to Mubende (Uganda) from Rwanda for gold mining ….Rwandese women who work in bars and also do sex work, others engage in escort services (prostitution at the border, either Cyanika PoE or Bunagana PoE…..” P2, FGD Cyanika

Religion and cultural

Respondents reported travel to attend various religious and cultural events including church services, pilgrimages, and cultural events such as circumcision.

“…...Ugandans, Kenyan, and Congolese also visit Kibeho(Rwanda) for religious services in August yearly….there also a number of Rwandese who travel for the annual Matyrs day Celebration in Namugongo (Uganda)….” participant 2 FGD Cyanika.

“…...Ugandans also Move to Kenya for festivals of circumcision they come from sironko Manafwa , Butiru , Bududa all the way dancing into Kenya and go back to Uganda…..” KII Lwakhakha

Healthcare

According to respondents, individuals travel to seek healthcare services on the other side of the border. Reasons for this included more affordable care or even free and specialist services. Communities from Rwanda and Kenya visited Ugandan health facilities near the border for free health services. Respondents in Kenya reported seeking specialist services such as Ophthalmology services in Tororo District (Uganda). Respondents in Uganda reported travelling to Kenya for better maternal health, immunisation, and geriatric services for the elderly in Kenya. Travellers visited Uganda for traditional healing services

“….The cost of health services is cheaper in Uganda. In Rwanda people complain that you need to pay for insurance to access medical services and without it they cross over to Uganda for free (Clare Nsenga Health Facility) / cheaper health services (other health facilities)….Rwandese come to Uganda for seeking health care services like antenatal care, delivery, postexposure prophylaxis because those services are free ….” Participant 8 FDG Cyanika

“.…..the Ugandan women come to Kenya for maternal services and antenatal services…. Kenya offers better packages for delivering mothers…. They always bring under 5 children because the health services in Kenya are free and they always give mosquito nets to mothers. The mothers who usually cross for health services to Kenya are of ages 30 to 40 years…” Participant 8 FDG Lwakhakha

Education

Education was one of the main reasons for travel. Respondents reported travelling for better and affordable education on the other side of the border of Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda. School going children around the border attended both day and boarding schools. Day scholars cross the border daily because they have to return to their homes. Students from Rwanda cross to Uganda to attend schools in Kabale like Sainte Jerome Ndama and Kisoro vision secondary school in Kisoro, and tertiary institutions like Kampala International University. Ugandan students cross to Rwanda to attend Kigali Green hills academy.

“…The two schools I mentioned (Rise and shine Primary school, Kisoro vision secondary school are where people from Rwanda send their children for education and they are boarding schools…..” KII DHO Kisoro

“…people come from Kapchorwa District to Eldoret for school, other schools visited in Kenya by Ugandans in Lwakhakha border include; Lena academy, Chepukui primary and secondary school and Namunde Primary school….” FGD P1 Lwakhakha

Social reasons for travel

People travel for social reasons including visiting family and friends and places of entertainment like bars, football fields on either side of the border. Some men have wives on both sides of the border (Kenya & Uganda) therefore they cross the border to visit relatives particularly in Bungoma and Mount Elgon.

“….Other cross to drink alcohol in Uganda during the market days– Kenyans come to Uganda to drink because they feel beer in Uganda is cheap and waragi (local spirit) is illegal in Kenya…..” KII DSFP

“..… people move from Lwakhakha village in Uganda to Lwakhakha in Kenya for football games at the Lwakhakha government football pitch…..” FDG P4 Lwakhakha

Movement patterns across the border

Points of Entry and Exit used

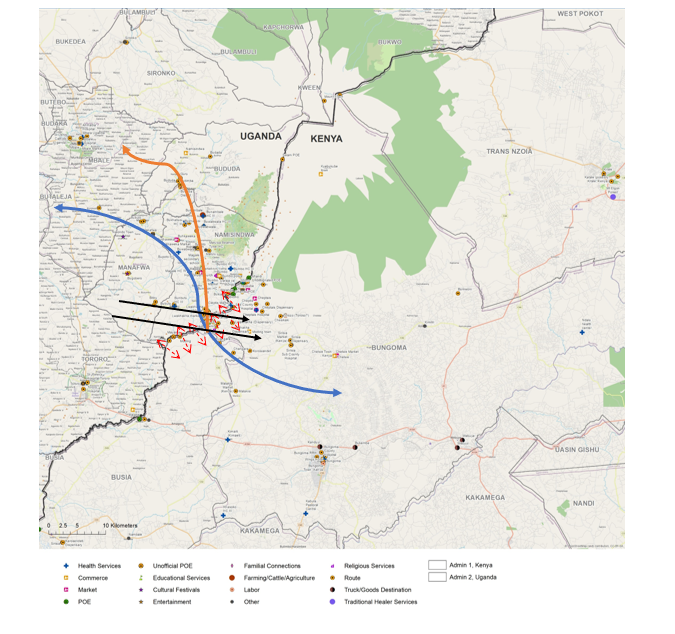

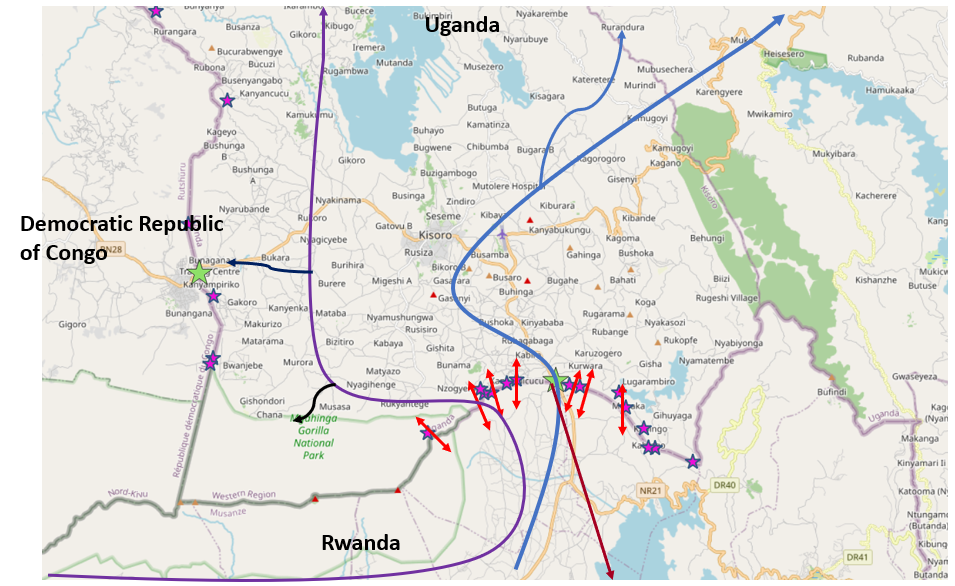

Respondents reported using both official and unofficial Points of Entry for exit and entry for movement across the border (Figure 1&2). The official Points of entry on the Uganda-Rwanda border include Cyanika, Katuna, and Mirama hills while of the Uganda-Kenya border has Lwakhakha, Swam, Busia, and Malaba.There are over 20 porous routes along the Namusindwa- Bungoma border and these included Soko mujinga, ‘Daraj ya mungu’, Mundidi, Chepkube, Bukhontso and Soono as the most frequently used illegal routes between the two countries. Porous routes on the Uganda_Rwanda border included Mgahinga, Kibaya, Kanyamucucu village, Rugabano, and Gatwe among others

Unofficial Points of Entry were preferred because they had less or no restrictions: like absence of screening, immigration check points which created a stop and were suitable environment for smuggling.

Some of the respondents were quoted saying:

“…People do not want to pass through the official border because they don’t want to be tested due its high cost, and they do not want to be checked…” FDG P3 Cyanika

“…the Lwakhakha border line is so porous, there are over 20 other routes through the border where people cross to either Uganda and Kenya because they do not have travel documents….” KII DHO Lwakhakha

“……animals move from Nyagatare in Rwanda to Nyakabande animal market while others go to Kyankwanzi and Nakasongora for animals grazing.” FGD P5 Cyanika

Frequency of travel and duration of stay

Respondents reported that the frequency of travel and duration of stay varied depending on the season and the reason for travel.

“…The truck drivers pass cross the border daily, Women/mothers cross daily and weekly, Ugandan looking for employment cross weekly and monthly, Sudan refugees weekly and monthly, Ugandans travelling for festivals of circumcision cross daily, Ugandans traders cross weekly every Tuesday and Saturday on the market days Ugandans crossing daily …” FDG P1 Lwakhakha

“…truck drivers stay for about 6-12 hours as they load and wait for goods, 3-4 days for individual coming in to seek medical services and more depending on the illness being sought treatment for, one day for traders who are just buying goods and going back to their homes or across the border and family visits which also depend on wish…female sex workers who go there on every Friday and come...” FDG P2 Cyanika

Volume of travellers and seasonality

The volume of travellers varied across seasons and key events on the other side of the border such as market days. Differences were reported between the type point of entry used (official vs unofficial).

“…on average, 5000 persons pass through porous borders per market day, and around 2000 persons on non-market days for casual work…..” FDG P1 Cyanika

“… From Uganda to Kenya movement is mainly January – April and June – August during cultivating and planting seasons… From Kenya to Uganda in December during cultural festivals….they generally move throughout the year but the months mentioned above have the most movements….”FDG P3 Lwakhakha

Means of transport

The participants that responded stated that travellers walk across, use motorcycles (“bodabodas”/ “tuktuk”), private and public vehicles and some are carried on the back to cross rivers.

“…People use Boda boda/ motorcycles,daily commuting buses/taxis and Foot through unofficial borders to avoid screening at the official PoE for fear of quarantine or isolation…at unofficial points people swim across the river or when the river is shallow, a guide holds the travellers hand and they are guided to walk through the river…” FDG P4 Lwakhakha

Response to public health events

Respondents on the Cyanika border reported reduced movements across the official border in fear of the Ebola outbreak.

“…….Yes they have restricted movement of people. Few people move across the border. But truck drivers are allowed to move with restrictions because they transport goods from one country to another….” FGD P3, Cyanika.

However, on the Lwakhakha border, movements were not restricted but screening was taking place, a respondent from a KII reported that; “…. people have continued to go about their business but with caution because we are at the border and anything is bound to happen…). Another responded reported reduced movements from Kenyan traders due to fear of the infection…” the movements have reduced among Kenyan traders due to fear of getting infected…” FGD P5, Lwakhakha border.

According to the border communities, Ebola virus disease was perceived to be very far from them; in Kampala and Mubende with no reason for worry. They reported that ebola had not scared them as much as coronavirus did.

Points of interest and routes

Points of interest included markets, places of worship, health facilities, education facilities and recreational/accommodation facilities (Figure 1& 2).

Discussion

Human mobility across the border has the potential to accelerate the spread of infectious diseases across countries. We explored human mobility patterns along the Uganda-Kenya and Uganda-Rwanda borders during an ongoing Sudan ebola virus outbreak in Uganda in November 2022. Our findings indicated that communities travel across borders for livelihood, healthcare, religious, social, and cultural purposes. Key destination points of travellers included high-volume areas such as markets, health facilities, places of worship, entertainment/recreation venues, schools and busy towns in Uganda and Kenya with confirmed EVD cases. Travellers preferred to use unofficial points of entry where there’s no screening and registration services.

Our findings indicated a potential for disease transmission with travel for healthcare and risky sexual behaviour. Ill travelers could potentially spread disease as observed in previous outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic (6). Risky behaviour such as commercial sex and alcohol consumption could increase sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV and syphilis at the border(7,8).

We found that travellers sought key health services such as maternal health, child health(immunisation), and HIV services. Travel for HIV services across the border highlights the need of ensuring the HIV continuum of care across the border. Previous studies in the region have indicated the need for tailor made strategies to support linkages to HIV services across the border(9). Similar to a previous study by Ssengooba et al ease of crossing the border, services being free, and availability of quality services facilitated seeking of health services across the border(10).

Movement from Kenya and Rwanda to areas in Uganda where there was an ongoing EVD outbreak presented a potential risk of transmission of EVD to these countries. Communities reported frequent travel with relatively long periods of stay in Uganda presenting opportunities for more human to human interaction thus possible exposure to disease. Key destinations in Uganda included Mubende, Jinja, and Kampala, which had confirmed EVD cases(11).

In both destinations with confirmed EVD cases and those without, travellers moved to high volume sites including markets, places of worship, and entertainment which are usually characterised by low surveillance and poor implementation of prevention measures. Further, the reported preference to use unofficial points of entry and with no screening and registration likely led to missed opportunities for case detection. Additionally, there are missed opportunities collecting information from travellers such as travel history and contact information which are key for case investigations. Previous studies have highlighted how the use of unofficial points of entry led to the spread of EVD in the West Africa EVD outbreak(12).

We highlighted a possible risk of transmission of zoonotic diseases due to animal trade and consequently movement of animals across the border along Uganda-Rwanda. Along the Uganda-Rwanda border, there is a risk of transmission of brucellosis, rift valley fever given that these diseases are endemic in Southwestern Uganda(13,14).

Conclusion

In conclusion, complex population movement and connectivity patterns were identified along the border. Communities travelled to high-volume service areas and busy towns in Kenya, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda for various reasons. Travellers preferred to use unofficial points of entry where there’s no going screening and registration services. Our findings were used to guide the Ministry of Health to enhance tailored cross-border disease surveillance including community-based surveillance in identified high risk areas and exit screening.

Public health actions

Based on these findings, there were heightened surveillance and preparedness efforts at health facilities near the borders which lead to identification of three suspected EVD cases travelling to Kenya from Uganda.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ministry of Health of Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda for the technical and financial support. We acknowledge the Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kenya Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Programme, and Rwanda Field Epidemiology Training Programme for availing us with the technical staff that executed this project. We appreciate the technical support provided by the Border Health Unit in the Division of Surveillance, Information and Knowledge Management. We thank Kisoro and Namisindwa District Local Governments, and the port health teams at Cyanika and Lwakhakha for their participation in this activity. Finally, we thank the US-CDC for supporting the activities of the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program (UPHFP).

Copyright and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- Affara M, Lagu HI, Achol E, Karamagi R, Omari N, Ochido G, et al. The East African Community (EAC) mobile laboratory networks in Kenya, Burundi, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, and South Sudan—from project implementation to outbreak response against Dengue, Ebola, COVID-19, and epidemic-prone diseases. BMC Med [Internet]. 2021;19(1):160. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02028-y

- Findlater A, Bogoch II. Human Mobility and the Global Spread of Infectious Diseases: A Focus on Air Travel. Trends Parasitol [Internet]. 2018/07/23. 2018 Sep;34(9):772–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30049602

- Searle KM, Lubinda J, Hamapumbu H, Shields TM, Curriero FC, Smith DL, et al. Characterizing and quantifying human movement patterns using GPS data loggers in an area approaching malaria elimination in rural southern Zambia. R Soc open Sci. 2017 May;4(5):170046.

- Pindolia DK, Garcia AJ, Huang Z, Smith DL, Alegana VA, Noor AM, et al. The demographics of human and malaria movement and migration patterns in East Africa. Malar J [Internet]. 2013;12(1):397. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-12-397

- CDC (US Centre for Disease Control). Population Connectivity Across Borders (PopCAB) Toolkit. 2021; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/popcab-toolkit.html

- Russell TW, Wu JT, Clifford S, Edmunds WJ, Kucharski AJ, Jit M. Effect of internationally imported cases on internal spread of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Public Heal [Internet]. 2021 Jan 1;6(1):e12–20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30263-2

- Morris CN, Ferguson AG. Estimation of the sexual transmission of HIV in Kenya and Uganda on the trans-Africa highway: the continuing role for prevention in high risk groups. Sex Transm Infect. 2006 Oct;82(5):368–71.

- Okiria AG, Achut V, McKeever E, Bolo A, Katoro J, Arkangelo GC, et al. High HIV and syphilis prevalence among female sex workers and sexually exploited adolescents in Nimule town at the border of South Sudan and Uganda. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0266795.

- Edwards JK, Arimi P, Ssengooba F, Mulholland G, Markiewicz M, Bukusi EA, et al. The HIV care continuum among resident and non-resident populations found in venues in East Africa cross-border areas. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019 Jan;22(1):e25226.

- Ssengooba F, Tuhebwe D, Ssendagire S, Babirye S, Akulume M, Ssennyonjo A, et al. Experiences of seeking healthcare across the border: lessons to inform upstream policies and system developments on cross-border health in East Africa. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1;11(12):e045575. Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/12/e045575.abstract

- Kiggundu T, Ario AR, Kadobera D, Kwesiga B, Migisha R, Makumbi I, et al. Notes from the Field: Outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease Caused by Sudan ebolavirus – Uganda, August-October 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022 Nov;71(45):1457–9.

- Cohen NJ, Brown CM, Alvarado-Ramy F, Bair-Brake H, Benenson GA, Chen T-H, et al. Travel and Border Health Measures to Prevent the International Spread of Ebola. MMWR Suppl. 2016 Jul;65(3):57–67.

- Nyakarahuka L, Whitmer S, Klena J, Balinandi S, Talundzic E, Tumusiime A, et al. Detection of Sporadic Outbreaks of Rift Valley Fever in Uganda through the National Viral Hemorrhagic Fever Surveillance System, 2017–2020. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2023;108(5):995.

- Asiimwe BB, Kansiime C, Rwego IB. Risk factors for human brucellosis in agro-pastoralist communities of south western Uganda: a case–control study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):1–6.

Comments are closed.