Cutaneous and Gastrointestinal Anthrax Outbreak Caused by Handling and Consumption of Meat from a Dead Cow in Kaplobotwo Village, Kween District, Uganda, April, 2018

Authors: Esther Kisaakye1, Kenneth Bainomugisha1, Lilian Bulage1, Alex R. Ario1; Affiliations: Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Kampala, Uganda

Summary

On 20-04-2018, 7 people were admitted with symptoms suggestive of cutaneous anthrax after handling meat from a dead cow, one of the four cows that died in a single kraal in Kween District, eastern Uganda. We investigated to; confirm the existence, determine the scope and magnitude of the outbreak, identify possible exposures and recommend evidence-based control measures. We line listed 48 human case persons (Attack Rate=21%) without deaths. Case-persons presented with signs and symptoms suggestive of either cutaneous (14/48), gas trointestinal (16/48), or a combination of two forms of anthrax infection (18/48). Males [AR=26% (33/127] and age group >18 years [AR=31% (30/96)] were the most affected. We conducted a retrospective cohort study and found out that handling/getting in contact with meat was a risk factor for cutaneous anthrax while eating meat from dead cow was a risk factor for gastrointestinal anthrax. We recommended treatment of all case-persons; vaccination of healthy animals; community education; supervised burial of carcasses; and prophylaxis to burial team.

Background

Anthrax is an acute zoonotic bacterial disease that is irregularly distributed worldwide in places where repeated outbreaks occur and is caused by Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax is transmitted to humans through getting in contact with/handling or eating meat of infected/dead livestock or their products (Dragon and Rennie, 1995). Historically anthrax has been described as occurring in four forms; cutaneous (CTN), inhalation (INH), gastrointestinal (GIT), and injection anthrax depending on the route of exposure (Hicks et al., 2012). On 20th April 2018, 7 people were admitted to Ngenge HCIII, after reportedly skinning, carrying, and eating a dead cow at Kaplobotwo village, Kween District, Eastern Uganda. They all presented with blisters, oedema and gram spots that are typical of an anthrax infection. Additionally, four cows were reported to have died within the same kraal in Kaplobotwo village, Kween District. We conducted an investigation to; confirm the existence of the outbreak, determine the scope and magnitude of the outbreak, identify possible exposures and recommend evidence-based control measures.

Methods

We defined a suspected anthrax case as; (1) onset of itching / reddening / swelling of skin areas and any of the following: skin lesions (e.g., papule, vesicle or eschar) and lymphadenopathy for cutaneous presentation and (2) onset of abdominal pain and any of the following: diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal swelling, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis and oropharygeal lesions for gastrointestinal presentation; in a person residing in Kaplobotwo village; Kween District from 6th April onwards. A confirmed case was defined as a suspected case with PCR-positivity for B. anthracis from a clinical sample i.e. swab from skin lesions/vesicles and blood. We conducted active case-finding to generate a line list at health facilities including clinics and in the affected villages. We collected 6 swabs and 8 blood samples from 8 suspected cases. We also conducted environmental assessments, trace back investigations, and a retrospective cohort study to identify the potential exposures of the outbreak.

Findings

Descriptive epidemiology: We line listed 48 human case-persons, of which 3 were confirmed, and 45 were suspected. The mean age of the case-persons was 29 years, range of 1 to 84 years, with overall attack rate (AR) =21% (48/234); and case-fatality rate=0%. Case-persons presented with

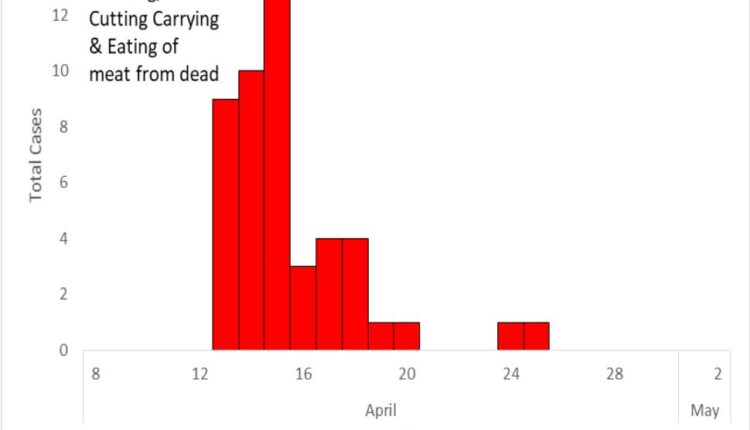

signs and symptoms suggestive of either cutaneous (14/48), gastrointestinal (16/48), or a combination of two forms of anthrax infection (18/48). The epidemic curve showed a typical point-source pattern with symptom onset starting on 13th to 25th April 2018 (Figure 2). Males [AR=26% (33/127] and age group >18 years [AR=31% (30/96)] were the most affected.

Retrospective cohort study: 80% of 10 people who participated in skinning dead cow, compared to those who didn’t (RR=4.2,95% CI=2.6-6.7) and 90% of 10 people who participated in cutting dead cow, compared to those who didn’t (RR=4.9,95%CI=3.2-7.5) developed CTN. 57% of 37 people who participated in carrying cut meat compared to those who didn’t (RR=4.9,95%CI=2.7-9.0) and 80% of 10 people who participated in cleaning waste from slaughter site compared to those who didn’t (RR=4.2,95%CI=2.6-6.7) developed CTN. 35% of 95 people who ate meat compared to those who didn’t developed GI anthrax (RR=∞,95%CI=∞–∞,Fisher’s exact p<0.00). Boiling meat for >60 minutes was protective (RR=0.49;95%CI=0.26-0.92).

Trace forward, environmental, and laboratory investigation findings

On 11th April 2018, a cow suddenly died at the home of resident X, one of the members of Kaplobotwo village. A total of 15 village members participated in slaughtering or dissecting, skinning, and carrying the dead cow’s meat on the same day. According to the village LC1 chairperson, almost the entire village ate the dead cow’s meat. Also, a portion of it (3 thighs and the cow’s head) was sold to neighbouring villages-Tukumo and Rikwo. In Tukumo village, the meat was sold to a bar, a restaurant and individual families.

However, we couldn’t trace all the exposed persons in this village because of the fact that the meat was distributed along the road. In Rikwo, the meat was sold to a bar, boiled by the bar owner and sold to his customers when ready for consumption. There was no case among his customers. At this point, one family of two people bought directly from the supplier of the implicated meat from Kaplobotwo village and both the two family members developed GIT symptoms after consuming the meat. In total 10 cows suddenly died in Kaplobotwo village within the same time frame. Three case-persons tested positive for anthrax by PCR

Discussion

In Uganda, over the years, anthrax has been occurring among animals with occasional leakage to humans. For humans, the major sources of exposure to B. anthracis are direct or indirect contact with infected animals or contaminated animal products (Hicks et al., 2012). This anthrax happened after the village members participated in the skinning, cutting, carrying and eating of meat from a cow that had suddenly died and whose cause of death was suspected to have been anthrax. The slaughter of anthrax infected animals and the disposal of butchering waste and carcasses in environments where ruminants live and graze, combined with limited vaccination, provides a context that permits repeated anthrax outbreaks in animals and zoonotic transmission to humans (Rume, 2018). Since the affected sub-county is located along the Moroto highway that crosses up to the border point between Kenya and Uganda, movement of animals along, in and out of the sub-county is highly possible.

Conclusion Public Health Actions, and Recommendations

This was a point source out break with a mixture of cutaneous & gastrointestinal anthrax forms likely caused by skinning, cutting, carrying, and eating meat from a dead cow. We educated the community about anthrax, treated all the sick case-persons identified in the community, supervised the burial of dead carcasses, and upon our recommendation the entire village vaccinated healthy animals on a private arrangement. We recommended vaccination of all healthy animals in Ngenge sub-county and surrounding areas and burial of carcasses under supervision of local and healthy leaders.

References

- Awoonor-Williams, J., Apanga, P., Anyawie, M., Abachie, T., Boidoitsiah, S., Opare, J., Adokiya, M.N., 2016. Anthrax outbreak investigation among humans and animals in Northern Ghana: Case report. Int J Trop Health 12, 1–11.

- Dragon, D.C., Rennie, R.P., 1995. The ecology of anthrax spores: tough but not invincible. Can. Vet. J. 36, 295.

- Hicks, C.W., Sweeney, D.A., Cui, X., Li, Y., Eichacker, P.Q., 2012. An overview of anthrax infection including the recently identified form of disease in injection drug users. Intensive Care Med. 38A, 1092–1104.

- Ndiva Mongoh, M., Dyer, N.W., Stoltenow, C.L., Hearne, R., Khaitsa, M.L., 2008. A review of management practices for the control of anthrax in animals: the 2005 anthrax epizootic in North Dakota–case study. Zoonoses Public Health 55, 279–290.

- Rume, F.I., 2018. Epidemiology of Anthrax in Domestic Animals of Bangladesh (PhD Thesis). University of Dhaka.

Comments are closed.