Trends and distribution of birth asphyxia, Uganda, 2017-2020: a retrospective Analysis of Public Health Surveillance Data

Authors: Allan Komakech1,2,3,4*, Stella M. Migamba1,2,3, Petranilla Nakamya1,3, Edirisa Nsubuga Juniour1,3, Job Morukileng1,2,3, Freda Aceng5, Robert Mutumba2, Lilian Bulage1,3 Benon Kwesiga1,3, Alex R. Ario1,3 | Institutional affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Kampala, Uganda, 2Reproductive Health Department, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda, 3Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, 4Clarke International University, Kampala, Uganda, 5Department of Integrated Epidemiology, Surveillance and Public Health Emergencies, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda *Correspondence: Email: akomackech@musph.ac.ug, Tel: +256789185617

Summary

Background: In 2015, Uganda adopted the interventions as advised by the Every Newborn Action Plan; these included a renewed focus on surveillance of birth asphyxia cases and adoption of a national strategic plan on managing birth asphyxia and other childhood related illnesses. In 2016, Ministry of Health integrated the Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) initiative, an evidence-based educational program to teach birth attendants about neonatal resuscitation techniques into the health system to improve management of birth asphyxia. We described the trends and distribution of birth asphyxia in Uganda during 2017–2020 in the era following the renewed efforts.

Methods: We analysed birth asphyxia surveillance data during January 2017–December 2020 obtained from the District Health Information System (DHIS2). We calculated incidence rates of birth asphyxia per 1,000 deliveries at district, regional, and national levels. We used line graphs to demonstrate the trend of annual incidence of birth asphyxia incidence with the corresponding reporting rates at national and regional levels. We used logistic regression to determine significance of trends.

Results: The average national annual incidence of birth asphyxia increased by 4.5% from 2017 to 2020 (OR=1.05; 95%CI=1.04-1.05, p=0.001), concurrent with a decline in reporting rates from 73% to 46% during the same period. The Northern and Eastern Region had a significant increase of 6% (OR=1.06; 95%CI=1.05-1.07, p=0.001) and 5% (OR=1.05; 95%CI=1.03-1.05, p=0.001) over the study period, respectively. The districts with highest incidence were Bundibugyo, Iganga, and Mubende with persistent rates of >60 cases of birth asphyxia/1,000 deliveries. The least affected district was Kazo District, with 3 cases of birth asphyxia/1,000 deliveries.

Conclusion: The incidence of birth asphyxia increased nationally from 2017-2020, even with declines in surveillance data reporting. There is a need to emphasize consistent reporting of birth asphyxia to ensure useful surveillance data. We also recommend continuous capacity building in managing birth asphyxia, with emphasis on the most affected districts.

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines birth asphyxia as the failure to initiate and sustain breathing at birth (1). Birth asphyxia is a leading cause of brain damage among new born children with up to 80% of survivors suffering from lifelong health problems such as disabilities, developmental delays, palsy, intellectual disabilities, and behavioural problems (2,3). Worldwide, birth asphyxia is responsible for an estimated 600,000 (24%) of all neonatal deaths per annum (4). In developed countries, birth asphyxia incidence is 2 per 1,000 births, which increases 10 fold in low-income countries with limited access to basic quality obstetrics care during pregnancy, intrapartum, and postpartum period (5). In studies done in Nigeria and Bangladesh, birth asphyxia was responsible for 30% and 39% of all neonatal deaths in the two countries respectively (6,7).

Birth asphyxia is associated with risk factors, which are grouped according to whether they are before birth (antepartum risk factors), during birth (intrapartum risk factors) or after birth (postpartum risk factors). Antepartum risk factors include severe maternal hypotension or hypertensive diseases during pregnancy, history of stillbirth, young maternal age, and advanced maternal age. Intrapartum risk factors include malpresentation, prolonged second stage of labour, and home delivery. Postpartum risk factors include low birth weight, high birth weight, preterm delivery, and poor resuscitation efforts. The majority of these causes are preventable, as evidenced by the regional variations across the world (8–11).

During 2018-2020, almost half of all neonatal deaths reviewed in Uganda were due to birth asphyxia (12). Studies done in Uganda implicated antepartum and intrapartum risk factors as the major culprits (13–16). Significant modifiable challenges in prevention of birth asphyxia include; complexities of referral systems, non-attendance of antenatal care by mothers, knowledge gaps among health workers, lack of equipment and high health worker: patient ratio (16).

In 2015, Uganda adopted the interventions as advised by the Every Newborn Action Plan; these included a renewed focus on surveillance of birth asphyxia cases and adoption of a national strategic plan on managing birth asphyxia and other childhood related illnesses. Furthermore, the Ministry of Health rolled out the Helping Babies Breathe (HBB) initiative in 2016; an initiative meant to improve prevention and management of birth asphyxia among health workers. However, the impact of these interventions on birth asphyxia incidence was unknown. We described the trends and distribution of birth asphyxia in Uganda during 2017-2020, the era following these renewed efforts.

Methods

Study setting

This study considered data that was collected nation-wide. Uganda is located in East Africa with an estimated projected population size of 41.6 million people (17)There are four broad regions in Uganda, each region is partitioned into districts making a total of 135 districts (17,18). Health is provided through a decentralized health care system whereby health services are delivered within seven tiers, including national referral hospitals, regional referral hospitals, district hospitals, health centre IV, health centre III, health centre II, and community health workers (CHWs), locally referred to as the Village Health Teams (VHTs) (20)In Uganda, birth asphyxia is a condition that can be managed at the level of HCII facilities and above.

Study design and data source

We conducted a nationwide retrospective surveillance data analysis of birth asphyxia cases from 2017 to 2020 using data abstracted from the Uganda District Health Information System (DHIS-2). Data on birth asphyxia was first entered in the DHIS-2 in 2017. DHIS-2 is a web-based reporting tool introduced to Uganda in 2012. It is a tool for collection, validation, analysis, and presentation of aggregate and patient based statistical data, tailored (but not limited) to integrated health information management activities.

Data on birth asphyxia data are routinely generated at health facilities using the integrated maternity register. The data from these registers are aggregated into a health facility monthly report (paper form) which is initially submitted to health sub-district, then to the district health offices. At district health office, the data from the paper-based reports are entered into DHIS-2. Data in DHIS-2 is then grouped accordingly at national, regional, district, subcounty and facility levels. At the national level, the Reproductive and Infant Health Department of the Ministry of Health and other stakeholders use data from DHIS-2 to make informed decisions and plan interventions on reproductive and infant health.

Study variables, data abstraction and analysis

We abstracted data for birth asphyxia cases and total deliveries during 2017–2020 from the DHIS-2. We disaggregated the data into national, regional, and district levels. We calculated the annual incidence rates for birth asphyxia cases for each level (national, regional, and district level), by dividing the total birth asphyxia cases during the year by the total deliveries during that year and multiplying by 1,000. We obtained the mean annual incidence rates for the national and regional levels by adding annual incidence rates for the four years of study and dividing by four.

We drew line graphs by plotting the quarterly mean incidence of birth asphyxia against the period in years to present the trend of incidence rates for national and regional levels from 2017–2020. We used logistic regression to establish the significance of trends of birth asphyxia incidence over the four years at national and regional level. We also used choropleth maps generated using Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) to present the district distribution of the birth asphyxia incidence across the country.

Ethical considerations

Our study utilized routinely generated aggregated surveillance data with no personal identifiers in reproductive and infant health department, Ministry of Health (MoH) through the DHIS-2. The MoH of Uganda through the office of the Director General Health Services gave approval to access data for birth asphyxia cases from the DHIS-2. We stored the abstracted data set in a password-protected computer and only shared it with the investigation team. In addition, The Office of the Associate Director for Science, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, determined that this study was not a human subjects research with the primary intent of improving use of surveillance data to guide public health planning and practice.

Results

Trend of annual incidence rate of birth asphyxia, national level, Uganda, 2017–2020

In Uganda, there were a total of 134,801 birth asphyxia cases and 4,625,336 total deliveries during 2017-2020. The average national incidence of birth asphyxia over the four years in Uganda was 29 per 1,000 total deliveries. The highest annual incidence (32 birth asphyxia cases per 1,000 total deliveries) over the four years was recorded in 2020.

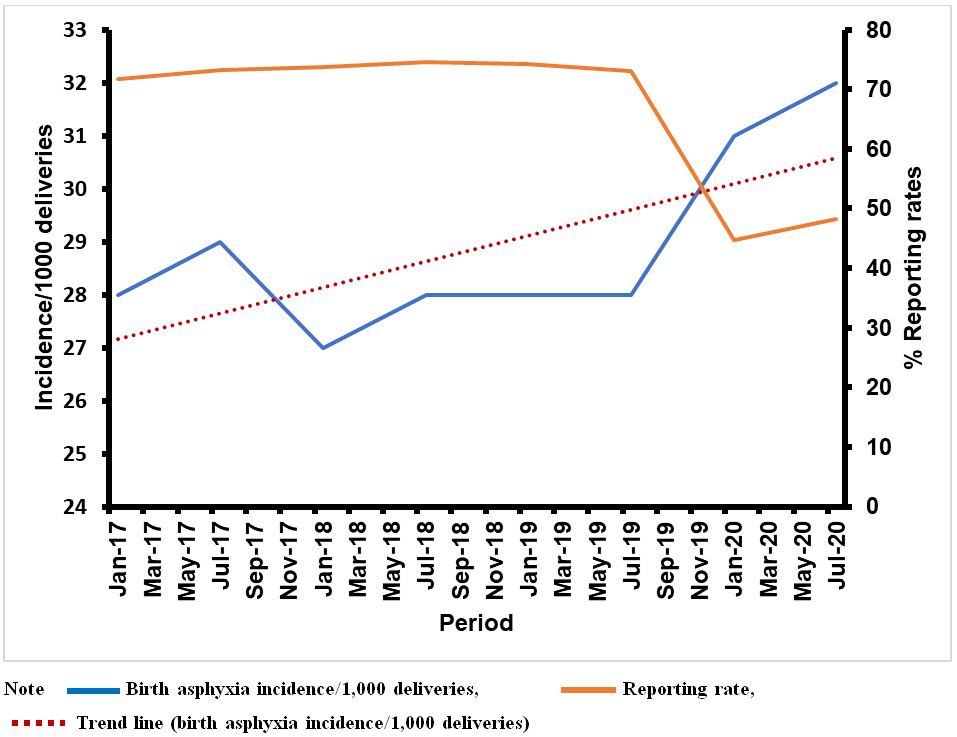

The incidence of birth asphyxia steadily increased by 5% from 2017–2020 and the increasing trend was shown to be statistically significant (OR 1.045; 95% CI 1.04, 1.05) (Figure 1). A concurrent decline in reporting rates from 73% to 46% is noted during the same period, 2017–2020.

Trend of annual incidence rate of birth asphyxia cases, regional level, Uganda, 2017-2020

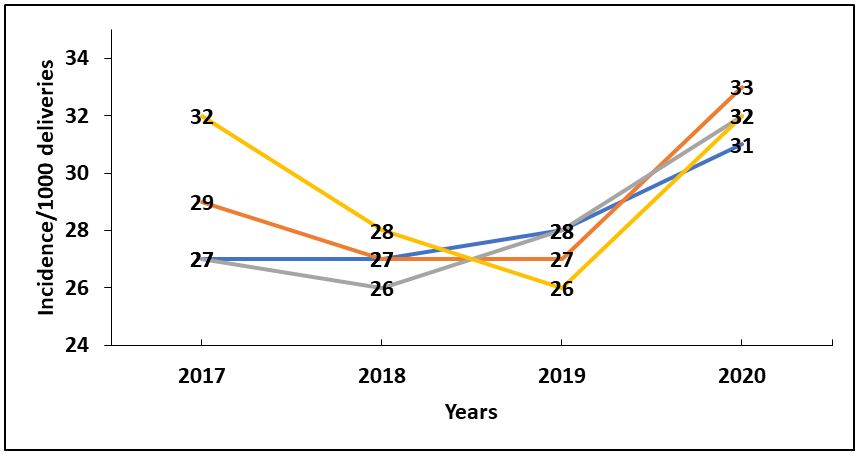

We also observed a statistically significant increase in the incidence rates of birth asphyxia/1,000 total deliveries in the Northern and Eastern regions of Uganda. Northern region had a 7% increment in birth asphyxia incidence while Eastern Region had a 5% increment in birth asphyxia incidence during 2017–2020 (Table 1).

Central region registered the highest mean annual incidence rate of 30 birth asphyxia cases/1,000 total deliveries over the four years and the Northern Region registered the lowest mean incidence rate of 28 per 1,000 deliveries over the four years. Although no major decreases or increases in the trends were noted in the Central region, incidence above the national average are consistently noted over the four years (Figure 2).

Table 1: Significance of trends of birth asphyxia incidence at regional level, Uganda, 2017–2020

| Region 2017/2020 | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-Value |

| Northern | 1.07 | 1.05-1.08 | <0.001* |

| Eastern | 1.05 | 1.04-1.06 | <0.001* |

| Central | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.54 |

| Western | 0.99 | 0.99-1.01 | 0.75 |

*indicates p value˂0.05

Spatial distribution of birth asphyxia incidence rates, district level, Uganda, 2017-2020

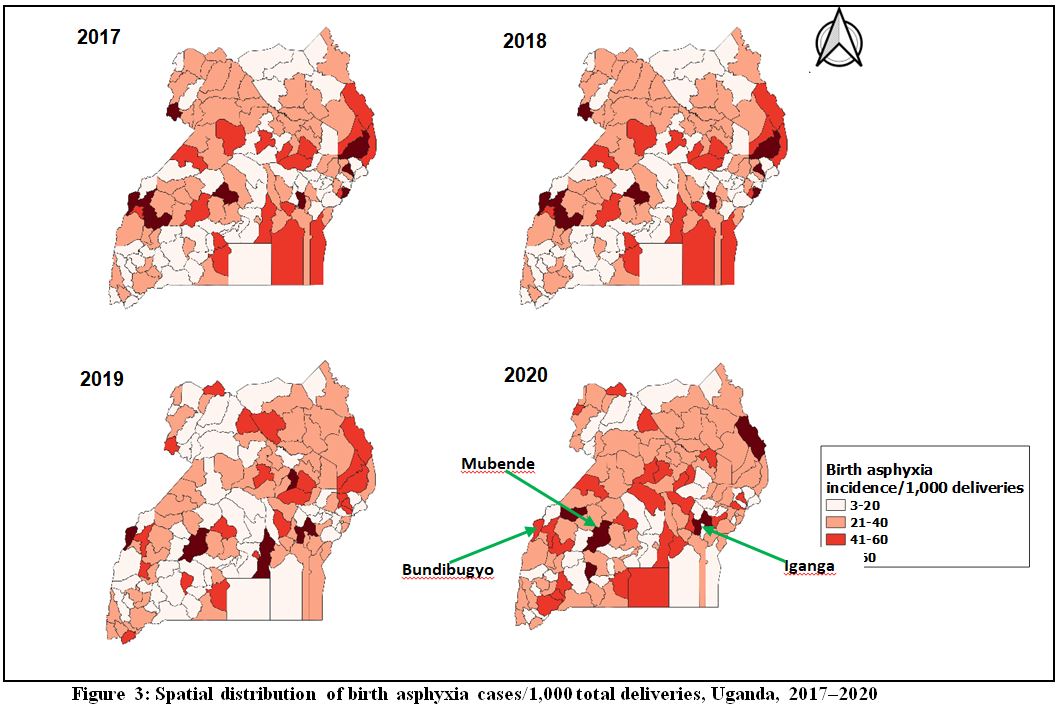

The spatial distribution of birth asphyxia cases over the four years shows a minimal clustering of high burden districts with similar patterns noted during all the four years of the study. The districts shaded in deep red had the highest incidence rates greater than 60 cases per 1,000 deliveries. The districts that had persistently high birth asphyxia incidence rates over the study period included Bundibugyo, Mubende, and Iganga. Moroto, Kabarole, and Kamwenge were also highly affected over the years. The districts with the white were the least affected (˂20 birth asphyxia cases per 1,000 deliveries) (Figure 3).

Discussion

Birth asphyxia incidence rates increased significantly by 5% in Uganda during 2017-2020. We also noted a statistically significant increase of 6% in the Northern region and 5% in the Eastern Region. The highest annual incidence of birth asphyxia cases was recorded in 2020 (32 birth asphyxia cases/1,000 total deliveries), compared to 28/1000 total deliveries in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Spatial trends showed minimal clustering of birth asphyxia incidence in the country with districts such as Bundibugyo, Iganga, and Mubende having persistently high birth asphyxia incidence rates over the four years (˃60 cases per 1,000 deliveries).

In our study, the incidence of birth asphyxia increased steadily by 5% over the study period despite a decrease in reporting rates over the same period. The increase in birth asphyxia incidence over the study period is not clearly understood. However, the burden of birth asphyxia is particularly high in East and Central Africa compared to other regions of Sub-Saharan Africa (21). This is due to poor obstetrics coverage, inequity and inequality because of gaps in local health financing models, inaccessible health facilities, socio-cultural norms, low literacy levels, shortage in health workers and supplies and poor health care spending (21).

Our study could not gather sufficient literature on birth asphyxia incidence in similar settings as Uganda. On the contrary, we noted a decrease in birth asphyxia incidence in a study done in Netherlands from 0.13% to 0.10% in a 9-year period preceding 2019 (0R 0.97; 95% CI 0.95, 0.99) (22). The decrease might have been attributed to a difference in setting. Uganda is a low-income country with low per capita GDP whereas Netherlands is a developed country with free health care and adequate resources for health for all citizens. Funding health services can lead to provision of services vital to reduce and prevent birth asphyxia. A key lesson to learn therefore is that increasing financing can improve newborn outcomes.

The highest incidence of birth asphyxia during the study period occurred in 2020 at 32 birth asphyxia cases per 1,000 deliveries compared to 28/1000 total deliveries in the three previous years. The spike is likely due to the delayed access of mothers to health facilities following the imposition of the COVID-19 lockdown travel restrictions (23). A study in Uganda showed an increase of 7% in birth asphyxia incidence in the period before versus during the early phase of the COVID-19 lockdown (24).

The COVID-19 pandemic caused massive disruptions throughout many Africa countries affecting many lives and livelihoods (25). These findings were supported by findings in Malawi, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria during the COVID-19 lockdown (26,27). Furthermore, crisis situations do not necessarily lead to reduction in reproduction and yet access to health services is greatly affected during such periods (28). Special considerations should therefore be ensured to facilitate the movement of mothers during lockdown situations to improve access to health care.

In our spatial analysis, districts such as Bundibugyo, Iganga, and Mubende had persistently high incidence of >60 cases of birth asphyxia/1,000 deliveries. Kazo District was the least affected district with 3 cases of birth asphyxia/1,000 deliveries. Although no particular reason can be identified to explain the non-clustered patterns of birth asphyxia in Uganda, all regions of Uganda have their fair share of poverty (29), issues with access to- and availability of health facilities (30), and differing cultural and social norms (31), known factors that can lead to birth asphyxia. Studies done to establish socio-demographic and health facility factors associated with birth asphyxia, particularly in the highly affected regions would be beneficial.

Study limitations

Secondary data in DHIS2 is limited in terms of variables to provide a sufficient assessment of birth asphyxia incidence in Uganda. Studies using primary data to determine associated factors may be more beneficial in understanding increasing birth asphyxia trends in Uganda. This will help to improve already-existing evidence-based interventions. Secondly, given the low average reporting rates over the study period (˂80%), a true representation of birth asphyxia incidence might be limited. It should also be noted that some deliveries occur outside the hospital; it is therefore possible that the incidence rates we are reporting here are an underestimate.

Conclusion

Birth asphyxia incidence increased over the four years of our study period despite a decrease in reporting rates. The highest incidence over the four years was recorded in 2020. Bundibugyo, Iganga, and Mubende districts had a persistently high birth asphyxia incidence (˃60/1,000 deliveries). Kazo district was the least affected district (3/1000 deliveries).

We recommend the Ministry of Health to emphasize consistent reporting of birth asphyxia to ensure useful surveillance data. We also recommend continuous capacity building in managing birth asphyxia, with emphasis on the most affected districts.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Ministry of Health for providing access to DHIS2 data that was used for this analysis. We appreciate the technical support provided by the Reproductive Health Department of the Ministry of Health. Finally, we thank the US-CDC for supporting the activities of the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program (UPHFP).

References

- Abdo RA, Halil HM, Kebede BA, Anshebo AA, Gejo NG. Prevalence and contributing factors of birth asphyxia among the neonates delivered at Nigist Eleni Mohammed memorial teaching hospital, Southern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth [Internet]. 2019 Dec 30 [cited 2021 Jun 7];19(1):1–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2696-6

- Zhang S, Li B, Zhang X, Zhu C, Wang X. Birth Asphyxia Is Associated With Increased Risk of Cerebral Palsy: A Meta-Analysis. Front Neurol [Internet]. 2020 Jul 16 [cited 2021 Jun 7];11:704. Available from: www.frontiersin.org

- Pospelov AS, Puskarjov M, Kaila K, Voipio J. Endogenous brain-sparing responses in brain pH and PO2 in a rodent model of birth asphyxia. Acta Physiol [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2021 Jun 7];229(3):e13467. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.13467

- Ahmed R, Mosa H, Sultan M, Helill SE, Assefa B, Abdu M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with birth asphyxia among neonates delivered in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Aug 1 [cited 2022 May 16];16(8):e0255488. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0255488

- Kune G, Oljira H, Wakgari N, Zerihun E, Aboma M. Determinants of birth asphyxia among newborns delivered in public hospitals of West Shoa Zone, Central Ethiopia: A case-control study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2022 May 18];16(3):e0248504. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248504

- Adebami OJ. Maternal and fetal determinants of mortality in babies with birth asphyxia at Osogbo, Southwestern Nigeria Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney (ARPKD) in a Nigerian newborn: a case report View project Management of Neonatal Jaundice View project. 2016 [cited 2022 May 18]; Available from: http://garj.org/garjmms

- Sampa RP, Hossain QZ, Sultana S. Observation of Birth Asphyxia and Its Impact on Neonatal Mortality in Khulna Urban Slum Bangladesh. Int J Adv Nutr Heal Sci. 2013 Dec 13;1(1):1–8.

- Aslam HM, Saleem S, Afzal R, Iqbal U, Saleem SM, Shaikh MWA, et al. “Risk factors of birth asphyxia.” Ital J Pediatr 2014 401 [Internet]. 2014 Dec 20 [cited 2021 Jul 22];40(1):1–9. Available from: https://ijponline.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13052-014-0094-2

- Igboanugo S, Chen A, Mielke JG. Maternal risk factors for birth asphyxia in low-resource communities. A systematic review of the literature. https://doi.org/101080/0144361520191679737 [Internet]. 2019 Nov 16 [cited 2021 Jul 22];40(8):1039–55. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01443615.2019.1679737

- Bayih WA, Yitbarek GY, Aynalem YA, Abate BB, Tesfaw A, Ayalew MY, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of birth asphyxia among live births at Debre Tabor General Hospital, North Central Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2020 201 [Internet]. 2020 Oct 28 [cited 2021 Jul 22];20(1):1–12. Available from: https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12884-020-03348-2

- Panna S. Risk Factors for Birth Asphyxia in Newborns Delivered at Nongkhai Hospital. Srinagarind Med Journal-ศรีนครินทร์เวชสาร [Internet]. 2020 Jun 20 [cited 2021 Jul 22];35(3):278–86. Available from: https://thaidj.org/index.php/SMNJ/article/view/9123

- MPDSR Report Uganda FY 2019_2020 Final report for Printing_2020.

- Arach AAO, Tumwine JK, Nakasujja N, Ndeezi G, Kiguli J, Mukunya D, et al. Perinatal death in Northern Uganda: incidence and risk factors in a community-based prospective cohort study. https://doi.org/101080/1654971620201859823 [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 20];14(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16549716.2020.1859823

- Ayebare E, Jonas W, Ndeezi G, Nankunda J, Hanson C, Tumwine JK, et al. Fetal heart rate monitoring practices at a public hospital in Northern Uganda – what health workers document, do and say. https://doi.org/101080/1654971620201711618 [Internet]. 2020 Dec 31 [cited 2021 Jul 20];13(1). Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/16549716.2020.1711618

- Hedstrom A, Mubiri P, Nyonyintono J, Nakakande J, Magnusson B, Vaughan M, et al. Outcomes in a Rural Ugandan Neonatal Unit Before and During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic: A Retrospective Cohort Study. SSRN Electron J [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2021 Jul 20]; Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3872622

- Ayebare E, Ndeezi G, Hjelmstedt A, Nankunda J, Tumwine JK, Hanson C, et al. Health care workers’ experiences of managing foetal distress and birth asphyxia at health facilities in Northern Uganda. Reprod Heal 2021 181 [Internet]. 2021 Feb 5 [cited 2021 Jul 20];18(1):1–11. Available from: https://reproductive-health-journal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12978-021-01083-1

- Uganda profile – Uganda Bureau of Statistics [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.ubos.org/uganda-profile/

- Maps & Regions | Uganda National Web Portal [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 23]. Available from: https://www.gou.go.ug/about-uganda/sector/maps-regions

- Kamya C, Abewe C, Waiswa P, Asiimwe G, Namugaya F, Opio C, et al. Uganda’s increasing dependence on development partner’s support for immunization – a five year resource tracking study (2012 – 2016). BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 May 24];21(1):1–11. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-021-10178-0

- Mansour W, Aryaija-Karemani A, Martineau T, Namakula J, Mubiri P, Ssengooba F, et al. Management of human resources for health in health districts in Uganda: A decision space analysis. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022 Mar 1;37(2):770–89.

- Usman F, Imam A, Farouk ZL, Dayyabu AL. Newborn Mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Why is Perinatal Asphyxia Still a Major Cause? Ann Glob Heal [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2021 Aug 12];85(1). Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6688545/

- Ensing S, Abu-Hanna A, Schaaf J, Mol BW, Ravelli A. 453: Trends in birth asphyxia among live born term singletons. Am J Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2013 Jan 1 [cited 2021 Aug 9];208(1):S197. Available from: http://www.ajog.org/article/S0002937812017024/fulltext

- National Population Council. the State of Uganda Population Report 2020 Impact of Covid-19 on Population and Development: Challenges, Opportunities and Preparedness the Republic of Uganda. 2020;1–93.

- Hedstrom A, Mubiri P, Nyonyintono J, Nakakande J, Magnusson B, Vaughan M, et al. Impact of the early COVID-19 pandemic on outcomes in a rural Ugandan neonatal unit: A retrospective cohort study. PLoS One [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Apr 7];16(12):e0260006. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0260006

- Lone SA, Ahmad A. COVID-19 pandemic-an African perspective. https://doi.org/101080/2222175120201775132 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jun 4]; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1775132

- Chimhuya S, Neal SR, Chimhini G, Gannon H, Cortina-Borja M, Crehan C, et al. Indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic at two tertiary neonatal units in Zimbabwe and Malawi: an interrupted time series analysis. medRxiv [Internet]. 2021 Jan 6 [cited 2022 Apr 7];2021.01.06.21249322. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.01.06.21249322v1

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994 Apr 1;38(8):1091–110.

- Foundation ER. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Uganda under the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020.

- Reinikka R, Mackinnon J. Lessons from Uganda on Strategies to Fight Poverty. 1999 Nov 30 [cited 2022 Apr 6]; Available from: http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/1813-9450-2440

- Dowhaniuk N. Exploring country-wide equitable government health care facility access in Uganda. Int J Equity Health [Internet]. 2021 Dec 1 [cited 2022 Apr 6];20(1):1–19. Available from: https://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-020-01371-5

- Ogunfowora OB, Ogunlesi TA. Socio-clinical correlates of the perinatal outcome of severe perinatal asphyxia among referred newborn babies in Sagamu. Niger J Paediatr. 2020;47(2):110–8.

Comments are closed.