Recurrent Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever in Uganda’s Cattle Corridor, 2025

Authors: Anne Loy Alupo1*, Vianney John Kigongo1, Winfred Nakaweesi1, Annet Mary Namusisi1, Irene Kyamwine1, Sarah Elayeete1, Gaston Turinawe2, Benon Kwesiga¹, Richard Migisha¹ Affiliations: ¹Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, 2Integrate Epidemiology Surveillance and Public Health Emergency, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda Correspondence*: Tel: +256 788 372187, Email:annealupo@uniph.go.ug

Summary

Background: Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a tick-borne zoonosis transmitted mainly by Hyalomma ticks through the livestock-tick-human cycle. Uganda reports sporadic outbreaks, mostly in the cattle corridor. We investigated to determine the magnitude of the outbreak, identify the likely source of infection, and recommend evidence-based control and prevention measures.

Methods: A confirmed case of CCHF was laboratory confirmed using reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) between February 15, 2025–March, 2025 in a residence of Kyegegwa District. We conducted record reviews, interviews with patients, relatives, traditional healers, and clinicians to gather data on patients’ demographics, symptom onset, and exposure history, and discussions with health and veterinary officials to explore One Health integration in zoonotic disease surveillance and response. Environmental assessments and tick and animal blood sampling were also conducted.

Results: One case was confirmed: a 28-year-old male livestock farmer with direct tick exposure, who sought care at multiple health facilities without suspicion of VHF, resulting in delays of 9 days before detection from symptom onset. Ninety-five ticks were identified as Rhipicephalus appendiculatus; all animal samples tested negative for CCHF virus. Farmers reported inconsistent tick control practices and communal grazing, while coordination between human and animal health sectors was weak.

Conclusion: Delayed detection, inadequate tick-control practices, and a lack of integrated One Health surveillance contributed to CCHF transmission risk. Strengthening integrated One Health surveillance, frontline diagnostic capacity, and promoting effective tick-control practices are critical for early detection and prevention of CCHF and similar zoonotic threats in Uganda.

Introduction

Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) is a tick-borne viral zoonosis caused by the CCHF virus (CCHFv). While found in various Ixodid ticks, Hyalomma species are the primary vectors and reservoirs (1, 2). Humans acquire infections through tick bites or direct contact with blood or tissues of infected livestock such as cattle, goats, and sheep, which act as amplifying hosts (1, 3). Human-to-human transmission can also occur via exposure to infectious blood or bodily fluids, particularly in healthcare settings with inadequate infection prevention and control (IPC) measures (1, 2). Clinically, CCHF presents with a sudden onset of fever, headache, myalgia, general body weakness, abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhoea, and may progress to mucosal bleeding, haemorrhage, and multi-organ failure in severe cases. While approximately 88% of infections are asymptomatic, about one in eight develops severe or fatal disease (1).

On March 7, 2025, the Fort Portal Regional Public Health Emergency Operations Centre received an alert from Bujubuli Health Centre IV, Kyegegwa District, of a suspected Viral Haemorrhagic Fever (VHF) case presenting with fever, abdominal pain, general weakness, and profuse bleeding. Laboratory testing confirmed CCHF on March 9, 2025. We investigated to determine the magnitude of the outbreak, identify the likely source of infection, and recommend evidence-based control and prevention measures.

Methods

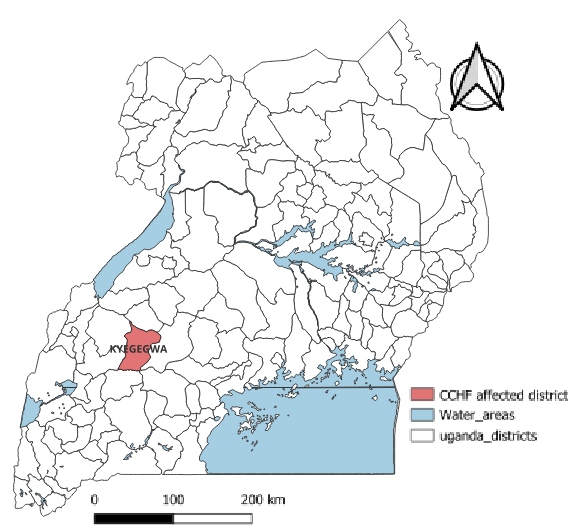

The outbreak was reported in Kaziizi village, Kyatega subcounty, Kyegegwa District, located in the South-western part of the country. Animal keeping is one of the main economic activities, and a dense network of livestock trade exists in this area.

We defined a suspected CCHF case as a sudden onset of fever (≥37.5°C) with a negative malaria test and at least 2 or more of any of the following signs and symptoms: general body weakness, headache, muscle pain, nausea, dizziness, blurred vision, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, joint pain, anorexia and/or unexplained bleeding between February 15, 2025–March, 2025 in a residence of Kyegegwa Districts. A confirmed case of CCHF was laboratory confirmed using RT-PCR at the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI), the national reference laboratory for VHF diagnosis in Uganda.

Using the Ministry of Health VHF case investigation form, we interviewed the case-patient, relatives, traditional healers, and clinicians who attended to the case to gather data on demographics, symptom onset, and exposure history. Medical records were reviewed, and an active community case search was conducted in Kaziizi Village to identify more cases. We conducted two Focused Group Discussions (FGD) in Kaziizi Village, with 12 small-scale and 12 large-scale farmers to assess grazing and tick control practices. Key Informant Interviews (KII) with the District Health Officer, Veterinary Officer, and Entomologist explored One Health integration in zoonotic disease surveillance and response.

We conducted an environmental assessment, collected ticks and animal blood samples (from goats and cattle, including those of the index case) for species identification at the National Animal Disease Diagnostics and Epidemiology Centre (NADDEC). Case-patient homes, communal grazing areas, and water points were inspected for possible exposures.

Data analysis

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively as frequencies and percentages. Qualitative data from FGDs and KIIs were analysed using content analysis.

Ethical Considerations

This investigation, part of the public health response to a confirmed outbreak investigation, was classified as non-research and authorized by the MoH, with approvals from district and facility authorities. Informed verbal consent, including for audio recording, was obtained from all participants. Patients’ identifiers were removed, and data were securely stored in a password-protected database accessible only to the team. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. § §See e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

Results

A 28-year-old male livestock farmer from Kaziizi Village, Kyegegwa District, with no travel history, reported hand-picking and crushing heavily infested ticks on his cattle one week before symptom onset. He developed sudden fever, headache, and weakness on February 28, 2025. He first sought care at a private clinic in Katamba, where malaria RDT was negative, but treated with artemether/lumefantrine. Then he went to a traditional healer on March 5, and he was attended to by 2 people, and on March 6, 2025, his condition worsened with epigastric abdominal pain. He visited a private drug shop in Katamba centre, where typhoid was suspected (untested) and treated, but symptoms persisted. Later that day, he visited another private clinic in Kyegegwa town; an ultrasound showed hepatomegaly and peptic ulcer disease, and he was managed as an outpatient without adequate PPE. On March 7, he presented to Bujubuli Health Centre IV with worsening abdominal pain, weakness, profuse haematemesis, and epistaxis. He was immediately isolated, and samples tested at UVRI confirmed positive for CCHF on March 9. He was evacuated to Fort Portal Regional Referral Hospital (FPRRH), received supportive care, and was discharged after 14 days following two negative PCR tests.

All 95 (100%) ticks collected were identified as Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Blood from 11 animals tested negative. Shared grazing areas and communal water points were potential hotspots for tick transmission and reinfestation despite farm-level control measures.

Tick control practices and challenges

Farmers in Kaziizi village practised varied but often ineffective tick control methods. Large-scale farmers sprayed weekly or biweekly, while smallholders sprayed monthly due to financial constraints. Goats and sheep were rarely treated, and improvised methods such as mixing acaricides with motor oil, smearing animals with leaves or cloth soaked in acaricides, or hand-picking ticks were common. Shared grazing areas and water points promoted reinfestation, while acaricide resistance, high costs, and limited veterinary access further hindered effective tick control.

“I mix acaricide with motor oil so it sticks longer. The shopkeeper said it helps, but I can’t afford the full dose every time…” – Farmer, Kaziizi village

“I use tree leaves to smear the medicine on the cows; it saves me a lot. I also pick the ticks by hand and crush them, because even after spraying, ticks have refused to die…” Small-scale farmer.

Shared grazing lands and water points amplified transmission risks.

“Our animals go to the forest reserve with everyone else’s. That’s where they get ticks again, even after spraying. I can’t control what other farmers are doing…” – Farmer, Kaziizi village

One Health approach gaps

Structural gaps hindered coordinated CCHF prevention and response. At the time of the outbreak, there was no functional One Health team, and interdepartmental communication between the human and veterinary sectors was minimal. The veterinary department did not prioritise CCHF in its routine surveillance, and no dedicated budget or policy supported integrated zoonotic disease control. The absence of a structured One Health framework limited the district’s capacity to detect, prevent, and respond effectively to zoonotic outbreaks like CCHF, highlighting the need for multisectoral collaboration.

“We don’t have a functional One Health team, information sharing is minimal, and CCHF is not among the diseases listed for monitoring…” – KII, District Veterinary Officer

Discussion

This investigation reports a single CCHF case in Kyegegwa District, within Uganda’s cattle corridor. Initial misdiagnosis due to nonspecific febrile symptoms reflects low clinical suspicion for VHFs among healthcare workers. The finding highlights persistent gaps in surveillance, vector control, and multisectoral coordination, and underscores the likelihood of undetected CCHF cases in endemic and neighbouring districts (2, 4, 5).

Tick surveillance identified Rhipicephalus appendiculatus as the predominant species, consistent with its role in CCHF transmission (6). Irregular acaricide use, misuse, and exclusion of small ruminants contribute to persistent tick populations and acaricide resistance, increasing the risk of viral transmission. This has been indicated in other studies (7-9). Shared grazing lands and communal water points further facilitate tick propagation.

The investigation also revealed weaknesses in the operationalisation of the One Health approach. The absence of functional teams, limited intersectoral collaboration, lack of dedicated budget, and guiding policies for coordinated zoonotic disease control. Similar institutional gaps have been observed in sub-Saharan Africa (2, 8, 10).

Finally, detection of CCHF during Ebola enhanced surveillance underscores the importance of integrated VHF surveillance systems capable of screening for multiple pathogens. Building healthcare provider capacity through training, continuous medical education, and routine VHF screening in febrile illness algorithms is essential to improve early detection and prevent transmission. Combined with effective tick control and functional One Health frameworks, are critical for CCHF prevention.

Study limitations

The outbreak magnitude may have been underestimated due to CCHF non-specific clinical presentation, limited diagnostic capacity, and low clinical suspicion. Tick samples could not be tested for CCHF virus due to reagent shortages, limiting confirmation of viral presence.

Conclusion

CCHF continues to recur in Uganda and is likely underreported. Ongoing transmission is driven by poor tick control, limited veterinary services, high acaricide costs, low clinical suspicion, and weak One Health coordination. Prevention efforts should prioritize routine CCHF screening for febrile illness, health worker training, strengthened tick control, including small ruminants and acaricide rotation, and operational district-level One Health systems

Public health actions: The investigation team provided health education to the residents of Kaziizi Village during the parents’ meeting at the primary school and to the farmers on CCHF transmission and prevention.

Author contributions: ALA led the study conceptualization, data collection, analysis, and article drafting. JVK, WN, AMN, and GT contributed to data collection, investigation, and writing. SE, IK, BK, and RM provided supervision, validation, and article review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Public Health Fellowship Program for technical guidance, the Kyegegwa District authorities for coordination and field support, and the staff of FPRRH, Bujubuli Health Center IV, and other visited facilities for case identification and investigation support. We also appreciate UVRI and NADDEC for laboratory and technical assistance throughout the investigation.

Copyrighting and licensing: All material in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin is in the public domain and may be used and printed without permission. However, citation as to source is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever: Key facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/crimean-congo-haemorrhagic-fever. 2025.

- Nasirian H. New aspects about Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) cases and associated fatality trends: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. Comparative immunology, microbiology and infectious diseases. 2020;69:101429.

- Bente DA, Forrester NL, Watts DM, McAuley AJ, Whitehouse CA, Bray M. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: history, epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical syndrome and genetic diversity. Antiviral research. 2013;100(1):159-89.

- Aslam S, Latif MS, Daud M, Rahman ZU, Tabassum B, Riaz MS, et al. Crimean‑Congo hemorrhagic fever: Risk factors and control measures for the infection abatement (Review). Biomed Rep. 2016;4(1):15-20.

- WHO. World Health Organization. Introduction to Crimean Congo haemorrhagic fever: managing infectious hazards: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/crimean-congo-haemorrhaigc-fever/introduction-to-crimean-congo-haemorrhagic-fever.pdf. 2018.

- Atim SA, Ashraf S, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Ademun AR, Vudriko P, Nakayiki T, et al. Risk factors for Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) virus exposure in farming communities in Uganda. J Infect. 2022;85(6):693-701.

- Djiman TA, Biguezoton AS, Saegerman C. Tick-Borne Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review of Pathogens, Research Focus, and Implications for Public Health. Pathogens. 2024;13(8).

- Zalwango JF, King P, Zalwango MG, Naiga HN, Akunzirwe R, Monje F, et al. Another Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever outbreak in Uganda: ongoing challenges with prevention, detection, and response. IJID One Health. 2024;2:100019.

- Shahhosseini N, Wong G, Babuadze G, Camp JV, Ergonul O, Kobinger GP, et al. Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever Virus in Asia, Africa and Europe. Microorganisms. 2021;9(9).

- Buregyeya E, Atusingwize E, Nsamba P, Musoke D, Naigaga I, Kabasa JD, et al. Operationalizing the One Health Approach in Uganda: Challenges and Opportunities. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10(4):250-7.

Comments are closed.