Outbreak of yellow fever among Un-Vaccinated children, Masaka District, Uganda, March-May 2019

Authors: Maureen Nabatanzi1, Gloria Bahizi1, Benon Kwesiga1, Alex Riolexus Ario1, Bernard Lubwama2 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda; Affiliations: 2Epidemiology and Surveillance Department, Ministry of Health, Uganda

Summary

Yellow fever remains a public health threat in Uganda. Despite the availability of a vaccine, Uganda has had several outbreaks; the most recent was in 2016 in the central and south western region. On 8th May 2019, the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) identified one yellow fever confirmed case in Masaka District through their sentinel surveillance system and laboratory sub-network. We investigated to determine the scope of the outbreak, identify possible exposures, and recommend evidence-based control measures. We reviewed medical records and conducted community case finding in Bukakata sub-county, Masaka District. We identified a total of 5 case-persons (1 confirmed, 2 probable, and 2 suspect). All case-persons were children, the average age was 11 (SD=5), ranging from 3 to 17 years. Case-persons reported fever (100%), headache (100%), and abdominal pain (85%). The index case developed symptoms on 19 March 2019, and the outbreak ended in May 2019. All case-persons were residents of Bukakata sub-county in Masaka District. None had received yellow fever vaccination. Most (2/5, 80%) lived near forests and reported seeing monkeys at their home or family farmland; 60% lived near stagnant water and swampy areas (60%). Aedes mosquitoes and larvae were isolated at homes and farmlands in Bukakata. This yellow fever outbreak affected unvaccinated children. Likely risk factors for transmission were being unvaccinated and living close to swampy and forested areas inhabited by monkeys. We recommended a vaccination campaign in Bukakata and surrounding areas.

Introduction

Yellow fever is an acute viral hemorrhagic disease. It is transmitted from human to human by Aedes mosquitoes. Mosquitoes acquire the virus by feeding on infected primates (human or non-human) and then transmit the virus from human to human in areas with high mosquito density and where most people are unvaccinated (1). The incubation period of yellow fever infection is 3 to 6 days. Ac-cording to the World Health Organization, severe symptoms include high fever, jaundice, unexplained bleeding, and eventually organ failure. Among the severe cases, the case fatality rate is 20-50% (2). There is no known treatment for yellow fever and emphasis is put on vaccination.

Uganda has a history of yellow fever outbreaks; the most recent one in 2016 affected Masaka, Rukungiri, and Kalangala districts (3, 4). Following the 2016 outbreak, a mass vaccination campaign was conducted in the affected districts with the aim of preventing further outbreaks.

On 8 May 2019, the Ministry of Health received notification of one confirmed case of yellow fever in Masaka District. The case was identified at Bukakata Health Centre III in Masaka which is one of 6 sentinel sites set up by UVRI for the surveillance of arbovirology infections. We investigated to determine the scope of the outbreak, identify possible exposures in order to recommend evidence-based control measures.

Methods

We defined a suspected case as any person from Bukakata sub-county with fever of acute onset (negative for malaria test, unresponsive to fever management and not explained by any other reasons) from March-May 2019, and any two of the following symptoms: joint pain, headache, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and back pain. A probable case was a suspected case with liver function abnormalities or with post mortem liver histopathology or with jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) or with unexplained bleeding. A confirmed case was a suspected or probable case with a laboratory positive result (serology, PCR or other tests) for yellow fever virus.

We reviewed Bukakata health center III patient records and engaged health workers to refer any cases that fit the case definition. We also actively searched for cases in the affected communities. We shared the case definition with community leaders and worked alongside them to identify case patients. We assessed the affected community to establish environmental factors that could explain the onset of the outbreak. In addition, we assessed for the presence of Aedes mosquitoes in the affected community. Dry ice was used as bait for the adult mosquitoes while larvae were collected from stagnant water on site.

Results

From March to May 2019, we identified 5 case-persons (1 con-firmed, 2 probable, and 2 suspect). The case-persons were children with a mean age of 11 (SD=5) and ranging from 3 to 17 years. All 5 case-persons were residents of Bukakata sub-county in the villages of Kabsese (2), Kaziru (2) and Bukakata (1). Case-persons presented with headache (5/5, 100%), abdominal pain (4/5, 80%), joint pain (3/5, 60%), vomiting (3/5, 60%), unexplained bleeding (2/5, 40%), and jaundice (2/5, 40%). None of the case-persons had received yellow fever vaccination. Most case-persons lived near forests (4/5, 80%), stagnant water (3/5, 60%), and swampy areas (3/5, 60%). Four case-persons (4/5, 80%) reported seeing monkeys at their home or family farm-land. The main activities in the affected communities were farming and fishing. The farmlands were located in forested areas, recently deforested areas, and swamps. Aedes mosquitoes and larvae mosquitoes were observed at the homes, farmlands, and areas surrounding the outbreak site.

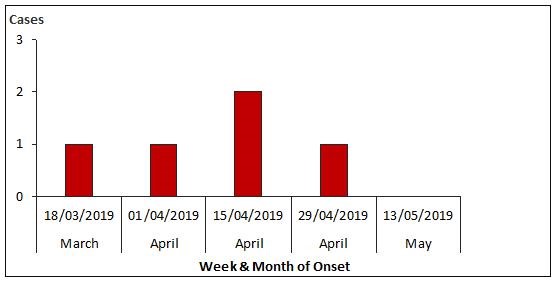

The outbreak occurred between March and May 2019; the index case developed symptoms on 19 March (week beginning 18 March) while majority of cases (4) occurred in April (Figure 2).

Discussion

Our investigation revealed that all the case-persons were residents of Bukakata sub-county Masaka District and living or farming in close proximity to forests or previously forested land inhabited by monkeys. Similarly, Kwagonza et al found an association between farming in monkey inhabited forest and swampy areas and yellow fever infection.(4). In the sylvatic (jungle) yellow fever transmission cycle, the virus is transmitted via mosquitoes from monkeys to humans when human activities encroach into the jungle (1).

It is recognized that presence of mosquito vectors and non-human primate hosts are involved in the YF virus transmission cycle (2). The environmental assessment revealed the presence of Aedes mosquitoes and larvae mosquitoes at the homes, farmlands, and areas surrounding the outbreak area. The rainy season months in this region are usually March, April, and May. These coincide with increased agricultural activities as farmers prepare their land for planting. During the investigation, it was raining heavily in the outbreak area which resulted in puddles of water around the homes of case-persons. It is likely that the heavy rains increased the stagnant water in the environment which encouraged the breeding of mosquitoes (4). This outbreak started in March and peaked in April; similarly, the 2016 yellow fever outbreak in Masaka District coincided with the rainy season and peaked in March and April (4).

The World Health Organization recommends vaccination as the most important intervention to prevent yellow fever [1]. After the 2016 out-break, a yellow fever mass vaccination campaign was conducted in Masaka. However, from our discussions with community members, some people especially children did not receive the vaccine during the campaign. In addition, the yellow fever vaccine has not been incorporated into the routine immunization schedule, it is therefore possible that there were unvaccinated people in Bukakata sub-county. This outbreak affected children who had not been vaccinated against yellow fever. Our investigation implied that this outbreak was likely sylvatic in nature, spread by the Aedes mosquitoes to an unvaccinated population living in proximity to mosquito breeding sites.

Conclusions and recommendations

This yellow fever outbreak affected unvaccinated children living in close proximity to monkey inhabited forested and swampy areas. We recommended that the Ministry of Health and Masaka District Health Team be supported to conduct a vaccination campaign in Bukakata sub-county with a special focus on children.

References

1. CDC. CDC Yellow Book 2020. Mark D. Gershman JES, editor. USA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019 August 02, 2019.

2. WHO. Background for the Consultation on Yellow Fever and International Travel. 2010.

3. Wamala JF, Malimbo M, Okot CL, Atai-Omoruto AD, Tenywa E, Miller JR, et al. Epidemiological and laboratory characterization of a yellow fever outbreak in northern Uganda, October 2010-January 2011. International journal of infectious diseases : IJID : official publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2012;16(7):e536-42.

4. Kwagonza L, Masiira B, Kyobe-Bosa H, Kadobera D, Atuheire EB, Lubwama B, et al. Outbreak of yellow fever in central and south-

western Uganda, February–may 2016. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2018;18(1):548.

Comments are closed.