On-going transmission of Leprosy and inadequate control measures in Lira and Alebtong Districts, Uganda, revealed by an epidemiological investigation, February-March 2019

Authors: Yvette Wibabara1, Gloria Bahizi1, Irene Kyamwine1, John Kamulegeya1, Doreen Gonahasa1, Maureen Nabatanzi1, Sandra Nabatanzi1, Gerald Rukundo1, Phoebe Nabunya1, Peter Muwereza1, Winfred Amia1, Maureen Katusiime1, Ronald Reagan Mutebi1, Daniel Kadobera, Alex R. Ario

Executive Summary

On 25 Feb 2019, the Lira District Biostatistician reported to Ministry of Health that 38 cases of leprosy had been identified in the last quarter of 2018. We investigated to confirm the existence of an out-break and identify the potential exposures. We reviewed the leprosy register at Lira regional referral hospital and conducted active case finding to generate a line list. We also conducted a case-control study to identify possible exposures. We identified 12 confirmed cases in 4 sub-counties of Barr, Ogur, Lira (Lira District) and Apala (Alebtong District). Barr was the most affected (Attack Rate=1.2 per 10,000). The possible exposures were; history of living in a camp, contact with a leprosy case patient, and poor hygiene practices although these were not statistically significant.40% of the cases had defaulted treatment which suggested possible on-going transmission. We referred all the identified case patients who were not yet on treatment to Lira Regional Hospital for initiation of Multi-Drug Therapy MDT. We also sensitized the VHTs on identifying leprosy lesions and referring patients to the health facilities for treatment and recommended screening of household members of case-patients so that any cases identified are initiated on treatment as early as possible.

Introduction

Leprosy is a chronic disease caused by a bacillus, Mycobacterium leprae. The average incubation period is 7-5 years (1). Leprosy is transmitted via droplets, from the nose and mouth, during close and frequent contacts with untreated cases. It mainly affects the skin, the peripheral nerves, mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, and the eyes. Leprosy is curable and treatment in the early stages can prevent disability(2).

Leprosy is still endemic in Uganda with some districts, being hot spots with unusually high numbers(3). The National Tb and Leprosy Program (NTLP) strategic plan 2015-2019 aims at reducing the incidence of Grade 2 disabilities among new leprosy cases from 2.3 per million population in 2014 to less than 1 per million population by 2019/20(4). In order to achieve this goal, NTLP targets to in-crease Multi Bacillary MDT completion from 91% in 2014 to 95% in 2020. On 25 Feb 2019, PHFP was notified by the Lira district Bio-statistician of a report of 38 leprosy cases in the last quarter of 2018. We investigated to verify the existence of an outbreak and establish the potential exposure factors.

Methods

We defined a confirmed case as onset of any 2 of cardinal symptoms of leprosy (Hypopigmented reddish lesion on skin, Loss of sensation in skin patch, enlargement of peripheral nerves) in a resident of Lira and Alebtong districts in the last 5 years.

We reviewed the leprosy register in Lira Regional Referral hospital and actively searched for cases in the affected communities and generated a line list. We performed descriptive epidemiology of the cases and generated hypotheses. To know whether this an outbreak, we re-viewed records in the District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2) and trends in hospital visits due to Leprosy from 2012-2018. We used hospital visits as proxy to new cases. We conducted a case control study to test the hypotheses.

Results

We identified 12 confirmed cases from 4 sub-counties of Barr, Ogur, Lira (Lira District) and Apala (Alebtong District). The Median age of the case-patients was 48 years, ranging from 24 to 72 years. Majority of the case-patients had signs and symptoms consistent with Leprosy. These were; numbness or tingling sensation 83% (9/12), pale/ reddish skin patches 83% (9/12), loss of sensation in the skin patch 83% (9/12) (Figure 1). Females (attack rate=3/10,000) were more affected than males (AR=2.3/10,000). 92% (11/12) had lived in an Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camp between 2005 and 2006

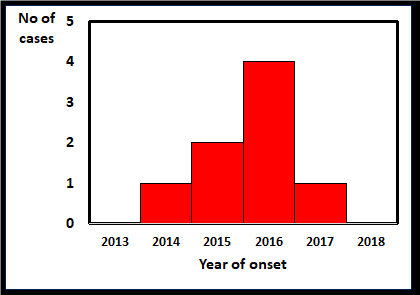

More leprosy cases identified in the year 2016 (Figure 2).

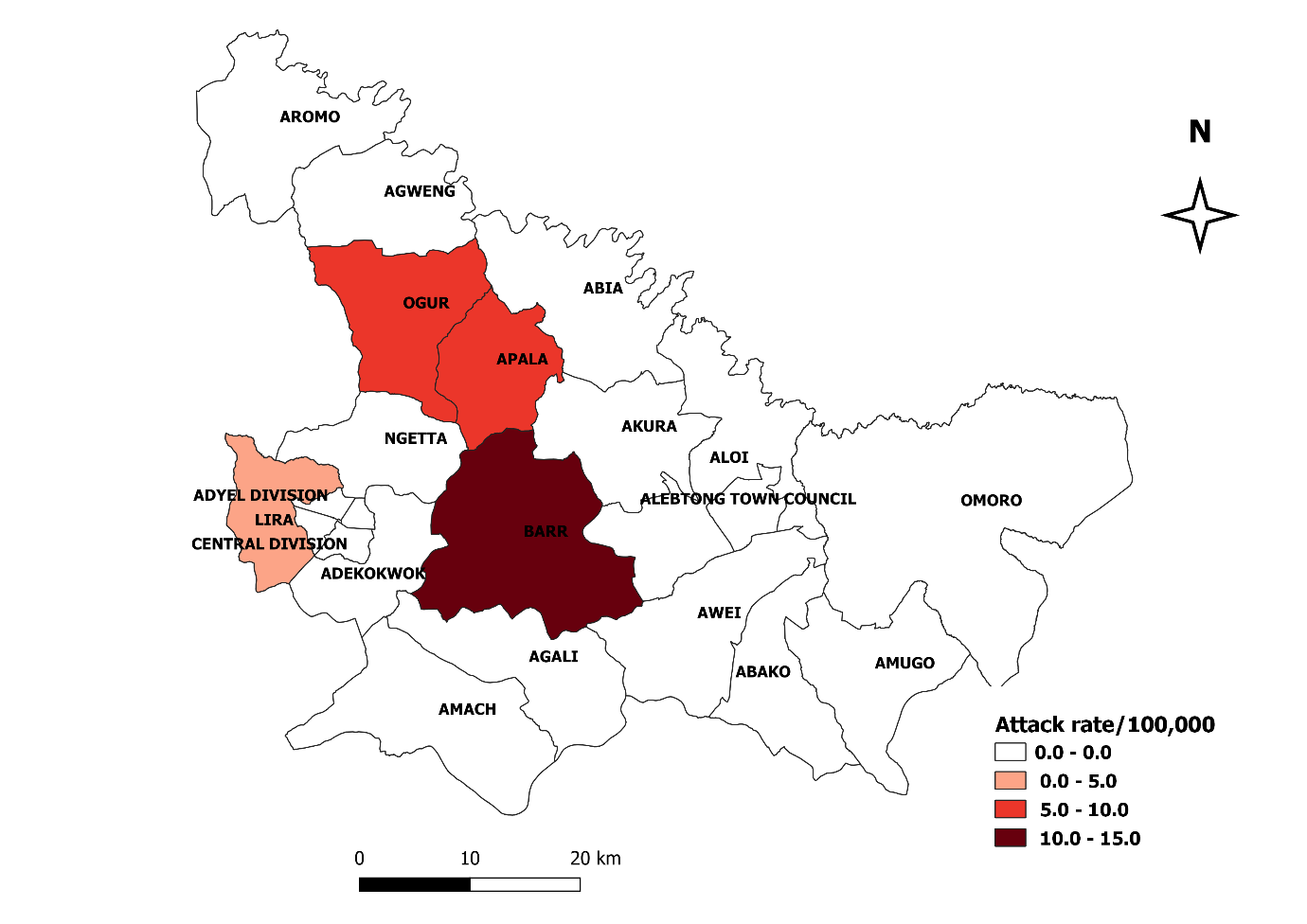

We identified 6 cases-patients from Barr (AR=1.2/10,000); 3 from Ogur (AR=0.7/10,000), 2 from Apala, and 1 from Lira. The cases were scattered with no specific pattern (Figure 3).

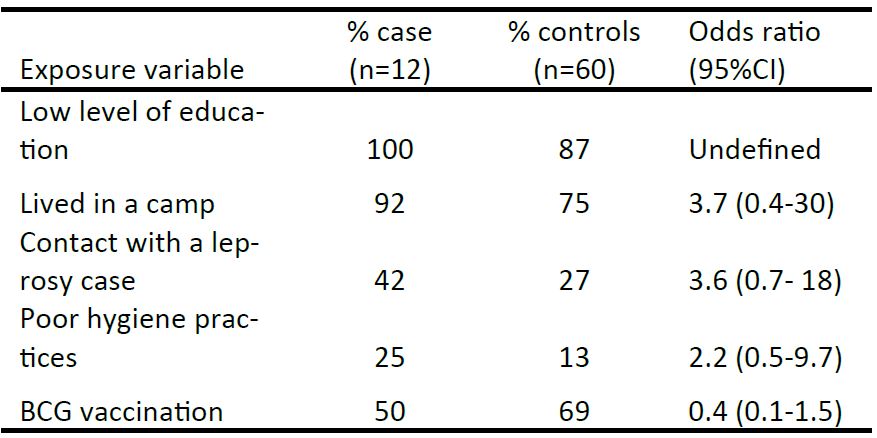

Hypothesis generating interviews revealed that 100% (12/12) had low level of education, 92% (11/12) had lived in a camp, 42% (5/12) had a history of living with a leprosy patient, 25% (3/12) had poor hygiene practices. We hypothesized that history of living in a camp was associated with Leprosy.

Case control study findings

Having lived in an IDP camp and being in contact with a person with leprosy were associated with acquiring leprosy though not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1: Association between exposures and leprosy among 72 respondents in Lira and Alebtong Districts, 2013-2018

Discussion

Our investigation confirmed presence of leprosy cases in Lira and Alebtong districts likely associated with history of living in a camp, contact with a person with leprosy, and poor hygiene practices. However, this association was not statistically significant likely due to a small sample size. Most of the cases were scattered in the communities and remote from health facilities, with about 40% reporting defaulting treatment. The high default rate suggests possible on-going transmission in the community. This transmission is further compounded by the fact that 92% of the cases reported no screening of their family members for Leprosy. And so, there is a missed opportunity for early identification of cases.

Ninety two percent of the cases had lived in an IDP camp between 2005 and 2006. It is possible that the exposure may have been the IDP camp. This could probably be due to the limited living space coupled with the crowding usually faced by people residing in IDP camps which increased their contact with case-persons and hence possible transmission of leprosy.

History of contact with a leprosy case-person was associated with having Leprosy. This was consistent with a systemic review of literature by Pescarini et al 2018 (3) which identified that being a house-hold contact of a leprosy patient increased the chance of getting Leprosy by 3 times.

This was not an outbreak of leprosy as evidenced from past records in District Health Information System 2 (DHIS2) and trends in hospital visits due to Leprosy from 2012-2018. We used hospital visits as proxy to new cases. The records suggested that this was not an outbreak, since there was no much deviation from the expected numbers.

Conclusions

This was not an outbreak of leprosy since the number of cases was not above the expected, however there is ongoing transmission in the community with inadequate control measures. The possible exposures may have been in the IDP camps during the war in Northern Uganda.

Public Health Actions and recommendations

We referred all the identified case patients who were not yet on treatment to Lira Regional Hospital for initiation of Multi-Drug Therapy MDT. We also sensitized the VHTs in identifying leprosy lesions and referring patients to the health facilities for treatment and recommended continuous surveillance to detect any fluctuations in the new cases diagnosed to inform decision making. We recommended screening household members of case-patients to ensure early identification and initiation of treatment to minimize transmission and complications.

References

1. WHO W. World Health Organization, What is leprosy? [Internet]. SEARO. 2019 [cited 2019 Mar 11]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/global_leprosy_programme/disease/en/

2. WHO W. Leprosy [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Mar 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leprosy

3. MOH Uganda. Manual for management and control of Tuberculo-sis and Leprosy in Uganda, 3rd Edition. 2.

4. National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme Revised National Strategic Plan 2015/16 – 2019/20 | Ministry of Health [Internet]. [cited 2019 Mar 11]. Available from: https://health.go.ug/content/national-tuberculosis-and-leprosy-control-programme-revised-national-strategic-plan-201516

5. MOH Uganda MU. Uganda National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program Revised Strategic Plan 2015/16 – 2019/20. 2015;

Comments are closed.