Increasing cases of malaria in Kampala City, Uganda: A descriptive analysis of surveillance data, January 2020–December 2023

Authors: John Rek1, Daniel Orit1, Gerald Rukundo2, Benon Kwesiga1, Richard Migisha1, Lilian Bulage1, Catherine Maiteki Sebuguzi2, Jimmy Opigo2, Alex Riolexus Ario1 Institutional affiliation: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda, 2National Malaria Elimination Division, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda Correspondence: Tel: +256-782-387-857, Email: jrek@uniph.go.ug

Summary

Background: Uganda ranks third in the global malaria burden. The country is experiencing rapid urbanization which predisposes the urban population to malaria transmission risks. Kampala City is the largest urban settlement in Uganda with poor housing in slums, encroachment on wetlands, and road construction with water stagnation which are high-risk factors for malaria transmission. We described the epidemiology of malaria in Kampala City to inform planning and malaria service delivery for city residents.

Methods: We conducted a descriptive study using secondary data abstracted from the District Health Information System-2 (DHIS-2) on patients tested for malaria, confirmed cases, hospital admissions, and reported deaths. Data was from 1,936 reporting health facilities, both public and private in Kampala City, between 2020 and 2023. We estimated the malaria incidence per 1,000 population per year by calendar year, gender, age group, and test positivity rates per calendar year. We used the Mann-Kendell test to test for the significance of the trends of cases, admissions, incidence, and test positivity rate.

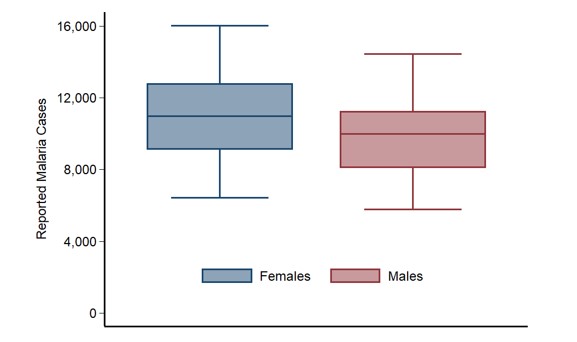

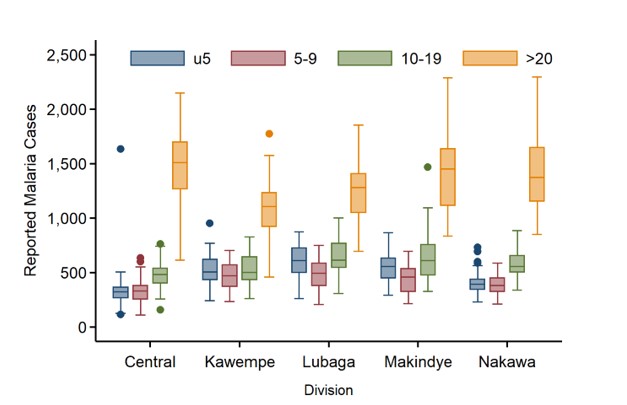

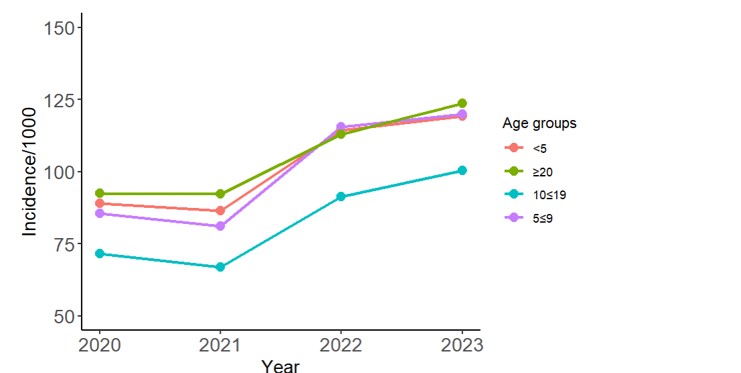

Results: Between 2020 and 2023, there were a total of 680,955 malaria cases, 25,836 malaria admissions, and 614 malaria-related deaths in Kampala City. Malaria cases increased by 29% from 144,697 to 203,842 (p-value=0.0001) and admissions by 55% from 4,319 to 9,592 (p-value 0.0001). Most (57.9%) admissions were among persons >5 years. Malaria incidence increased from 165 to 233/1,000 (p-value 0.0001) and was overall highest in females (405/1,000), adults ≥20 years (420/1,000), and in the Central Division (368/1,000). The mean monthly malaria test positivity rate from 2020 to 2023 was 17% (sd 4.4), with no significant trend (p-value=0.9). Most deaths were reported in children under 5 years (73%, n=448).

Conclusion: Malaria cases and incidence increased in Kampala City between 2020 and 2023. Targeting children under 5 and hotspot mapping to identify and characterize foci of malaria transmission in Kampala City will facilitate targeted interventions.

Introduction

Like the rest of Sub-Saharan Africa, Uganda is facing growth in the urban population and urbanization. The urbanization rate in Uganda is estimated at 5.2% and over 20% of the population is resident in urban centers1. The number of urban centers has increased from 259 in 2014 to 625 in 20212 and the urban proportion of the national population has grown between 15% in 2000 to 26% in 20223.

Along with urbanization are challenges that predispose people to malaria. These include poor urban planning leading to the proliferation of slums and informal settlements characterized by poverty, poor living conditions, substandard housing, overcrowding, and poor access to services; deterioration of the urban environment due to wetland encroachment for house construction; stagnant water in many places due to the poor state of roads creating breeding sites; and the proliferation of house construction sites. Several man-made breeding sites, including swimming pools, improperly disposed containers acting as breeding sites, tire tracks, and even overhead water tanks, are also common. All these factors provide a suitable environment for mosquito breeding thus increasing transmission5. In addition, urban malaria is characterized by low immunity due to low exposure from low transmission, importation of malaria from travelers, and private sector-led service delivery4–6. Severe forms of malaria are also common in urban settings due to the low immunity of the city residents.

Kampala is the capital city of Uganda and the largest urban settlement in the country. The city is characterized by a low malaria burden and reported to have a Plasmodium falciparum prevalence in 2-10 year old of <1%7. Like other cities, a challenge for malaria is an understanding of whether malaria in the city arises from local transmission or importation from nearby rural areas4. To better plan for malaria control in the city, a proper understanding of the epidemiology of malaria is thus important.

We described malaria patients reported in Kampala, trends in malaria test positivity rates and cases, and the spatiotemporal distribution of malaria incidence Kampala, 2020-2023.

Methods

This was a descriptive study of monthly passively collected malaria surveillance data submitted into the DHIS2 by health facilities in Kampala using the Health Management Information System (HMIS – 105 and 108), 2020-2023.

The capital city of Uganda is Kampala, with the Kampala Capital City Authority being the administrative unit. It is located in the southern part of the country, on the northern shores of Lake Victoria, and has five administrative divisions. Fifteen percent of the city is made of valleys filled with rivers and swamps that make good breeding sites for malaria vectors.

We abstracted monthly data from DHIS-2 at the division level including malaria cases (outpatient and inpatient), malaria tests done, tests positive by blood slide and rapid diagnostic test, and malaria deaths. Population data to calculate incidence was obtained from the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS). These included population estimates for Kampala city and divisions. Age-specific proportions provided by UBOS were applied to the populations to determine age-specific populations.

The proportion of malaria cases reported from the outpatient department was determined by gender and age group, and inpatient cases (admissions) by age groups (<5 and ≥5 years). Incidence was estimated as the cases per 1000 population per year, age group, and division. The test positivity rate was estimated as the proportion of all fever cases tested and positive for malaria. The seasonal Mann-Kendall test was used to test for significance of trends. Finally, the spatiotemporal distribution of malaria incidence per division were mapped.

We conducted a descriptive study using aggregated malaria surveillance data from all health facilities across Kampala Capital City that report through the DHIS-2. The Ugandan Ministry of Health permitted us to access and utilize the data. In addition, the office of the Center for Global Health, US Center for Disease Control and Prevention determined that this activity was not human subject research and with its primary intent being for public health practice or disease control. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. § § See e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

Results

Characteristics of malaria cases, Kampala, 2020-2023

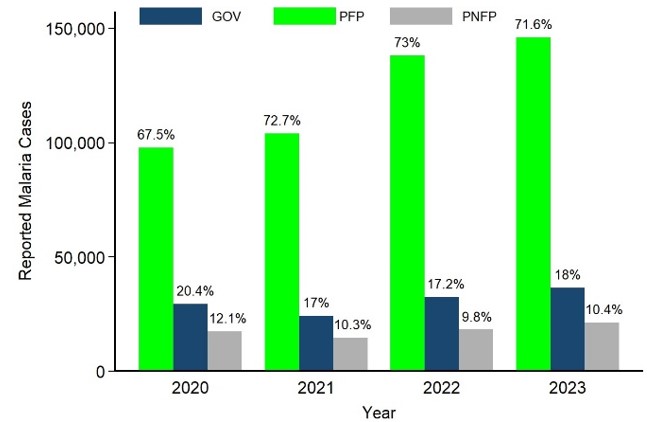

Between 2020 and 2023, 680,955 malaria cases, 25,836 admissions, and 613 deaths were reported in Kampala. The majority 71.4% (486,003) of the cases were reported from Private For-Profit health facilities (Figure 1) and 73% (448) of deaths in children under 5 years of age.

Figure 2: Distribution of malaria cases by gender, Kampala, 2020-2023

Proportion of admissions and admission incidence by age group per year, Kampala, 2020-2023

A total of 25,836 malaria admissions were reported in the study period. The majority 58% (14,930) of admissions were in the > 5-year age group. However, the average incidence of admissions in the children <5vears was 95/10,000, and has been increasing since 2020 (Table 1).

Table 1: Proportion of admissions and admission incidence by age group per year, Kampala, 2020-2023

| u5 | >5 | |||||||

| year | n | % | Population | incidence/10,000 | n | % | Population | incidence/10,000 |

| 2020 | 1916 | 43.8 | 278,980 | 69 | 2403 | 55.6 | 1,401,620 | 17 |

| 2021 | 1512 | 38.0 | 283,843 | 53 | 2410 | 61.4 | 1,426,057 | 17 |

| 2022 | 3560 | 44.2 | 288,608 | 123 | 4443 | 55.5 | 1,449,992 | 31 |

| 2023 | 3918 | 40.6 | 293,239 | 134 | 5674 | 59.2 | 1,473,261 | 39 |

| Overall | 10906 | 41.6 | 95 | 14930 | 57.9 | 26 | ||

Trend of incidence of malaria, Kampala, 2020-2023

There was a general increase in the overall incidence of malaria in Kampala by 34%, from 86/1000 in 2020 to 115/1000 population in 2023. Additionally, incidence increased in all age groups. The incidence was higher in the ≥ 20-year age group in 2020 and 2021. In 2023, the incidence is comparable between the <5, 5≤9, and ≥ 20-year age groups (Figure 4).

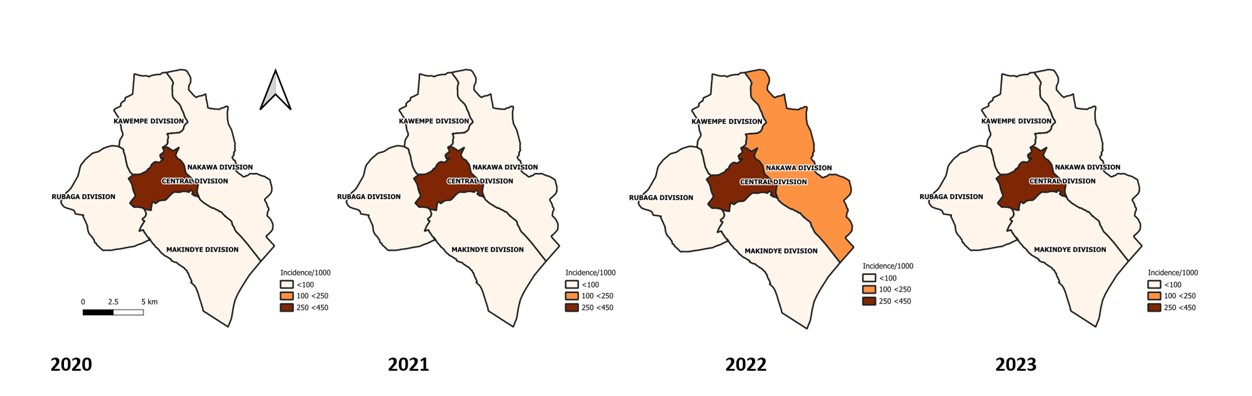

Spatiotemporal distribution of malaria incidence, Kampala, 2020-2023

The Central division of Kampala had a consistently higher incidence from 2020 to 2023. Incidence in the central division increased from 314/1000 in 2020 to 444/1000 in 2023 (Figure 5).

Discussion

This descriptive analysis of malaria in Kampala, shows an increasing trend since 2020, females and adults above 20 years contributing the most cases and children under 5 years are the most affected by malaria. We also show that central division had the highest malaria incidence, and private for-profit health care providers are the predominant channels for malaria treatment.

These findings are also consistent with other studies that indicated increasing cases of malaria in most urban settings since 20038. They also confirm the long known fact that urbanisation in Africa may be challenged by increases in malaria transmission, contrary to the earlier beliefs that urbanisation would result in declines in transmission.9,10

The study found that adults ≥ 20 years reported the most malaria in Kampala city. This finding was consistent across the divisions of Kampala city. This could be due to the population structure of the city, where adults above 20 years constitute approximately 44% of population11. It is also possible that the day time population from the metropolitan area that travel into the city, is diagnosed in the city, constituting malaria importation in the city. Considering the low transmission levels in Kampala, importation of malaria by the travelling adult population is another potential source of malaria infection and disease in the adults12.

Malaria affected children under five years more than other age groups. Findings from this study are consistent with those from other studies, that show that indeed children under five years suffer more from malaria13,14. Children under five are more susceptible to malaria because of the low and immature immune response to malaria unlike the older children and adults14. Due to repeated exposures, older children and adults tend to develop better antiparasitic immune responses, thus lowering their susceptibility to malaria15. Malaria infection in the children could arise from local transmission within the city or from infection during recent overnight travel out of Kampala. A study in Kampala showed recent overnight travel away from Kampala –in a low transmission setting, was associated with malaria. It also showed that more cases than controls in children under five years diagnosed with malaria in Kampala, had recent overnight travel12.

The high incidence of malaria in the central division compared to other divisions of Kampala could be attributed to the high day time population coming to the central business district for trade and consequently seeking care within the health centres in the central division. The day time population is approximately 4 million people, originating from the greater Kampala metropolitan area in addition to the city residents. These non-resident population could be diagnosed with malaria within the central division, creating a pseudo higher burden in the city. Knowledge of the geolocations of the people testing positive for malaria in the central division, would improve understanding of the spatial epidemiology of malaria in the division. A study in Maputo City, Mozambique emphasizes the importance of enhanced surveillance including collection of geolocation data for better characterisation of malaria in the urban setting16. The role of importation of malaria parasites into cities that was demonstrated in a study in Madagascar 17, that showed that travel into the cities that form major “sinks” by parasitized individuals contributes to malaria burden in the cities.

The majority (60%) of people in Uganda seek care first from the private sector7, and yet in Kampala, over 80% of health facilities are private for profit owned. This implies, a higher proportion of city residents access care from the private sector compared to the rest of the country. The role of the private sector in malaria service provision has been reported elsewhere, as of importance18. Malaria is a leading killer of children, especially those under 5 years. Like other studies and reports, Kampala city malaria mortalities show that u5s suffered the most deaths due to malaria, at 72.2%. These findings are comparable to reports from the WHO world malaria report of 2023 that showed that though there were declines in u5 deaths due to malaria, this has since stalled at 76% since 201519. Children u5 years are at risk of severe malaria due to loss of maternal protection and an immature immune system14.

Study limitations

This study had some limitations including, the data from DHIS-2 is aggregate data and the age groups are predetermined in the dataset. We were thus not able to describe the epidemiology of malaria at individual level. Most of the facilities providing care in the city are private for-profit entities. These are challenged by reporting using the HMIS system. The true magnitude of malaria in the city may thus have been underestimated.

Conclusion

Malaria in Kampala city, the largest urban settlement in Uganda has been increasing since 2020. The most affected are females, children under 5 years and the central division of Kampala. Malaria mortalities are high in the under 5s. Most of the malaria cases in Kampala are treated in the private sector. We recommend, identifying hotspots for malaria in Kampala for better intervention targeting, Prioritization of malaria surveillance and case management in the private sector, and risk communication for prevention and early treatment of malaria should be tailored for Kampala, to avert malaria deaths.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest.

Authors contribution

JR, designed the study and contributed to data analysis. JR led the writing of the bulletin. DO, GR, BK, RM, LB, CM, JO, and ARA participated in bulletin writing and review to ensure scientific integrity and intellectual content. All authors contributed to the final draft of the bulletin. All authors read and approved the final bulletin.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the PHFP for the technical support offered during the conduct of this study.

Copyrights and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin are in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- Ministry of Lands Housing and Urban Development. Uganda National Urban Policy, 2017. https://mlhud.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/National-Urban-Policy-2017-printed-copy.pdf.

- Ministry of Lands Housing and Urban Development. Uganda State of Urban Sector Report 2021-2022. (2022).

- The World Bank. World Bank Open Data. World Bank Open Data https://data.worldbank.org.

- Wilson, M. L. et al. Urban Malaria: Understanding its Epidemiology, Ecology, and Transmission Across Seven Diverse ICEMR Network Sites. Am J Trop Med Hyg 93, 110–123 (2015).

- Kigozi, S. P. et al. Associations between urbanicity and malaria at local scales in Uganda. Malaria Journal 14, 374 (2015).

- Hay, S., Guerra, C., Tatem, A., Atkinson, P. & Snow, R. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat Rev Microbiol 3, (2005).

- NMCD, UBOS. Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey 2018-2019. https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/MIS34/MIS34.pdf.

- Doumbe-Belisse, P. et al. Urban malaria in sub-Saharan Africa: dynamic of the vectorial system and the entomological inoculation rate. Malar J 20, 364 (2021).

- De Silva, P. M. & Marshall, J. M. Factors Contributing to Urban Malaria Transmission in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Journal of Tropical Medicine 2012, e819563 (2012).

- Donnelly, M. J. et al. Malaria and urbanization in sub-Saharan Africa. Malaria Journal 4, 12 (2005).

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Abstract, 2022. (2022).

- Arinaitwe, E. et al. Malaria Diagnosed in an Urban Setting Strongly Associated with Recent Overnight Travel: A Case-Control Study from Kampala, Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg 103, 1517–1524 (2020).

- Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2022, C. World malaria report 2022. (2022).

- Ranjha, R., Singh, K., Mohan, M., Anvikar, A. R. & Bharti, P. K. Age-specific malaria vulnerability and transmission reservoir among children. Global Pediatrics 6, 100085 (2023).

- Rodriguez-Barraquer, I. et al. Quantification of anti-parasite and anti-disease immunity to malaria as a function of age and exposure. eLife 7, e35832.

- Stresman, G. et al. Optimizing Routine Malaria Surveillance Data in Urban Environments: A Case Study in Maputo City, Mozambique. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 108, 24–31 (2023).

- Ihantamalala, F. A. et al. Estimating sources and sinks of malaria parasites in Madagascar. Nat Commun 9, 3897 (2018).

- Silverman, R., Rosen, D., Regan, L., Vernon, J. & Yadav, P. Malaria Case Management in the Private Sector in Africa: A Call for Action to Identify Sustainable Solutions.

- Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2023, C. World malaria report 2023.

Comments are closed.