Evaluation of the Disease Surveillance System in Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement, Kiryandongo District, April 2017

Authors: Denis Nixon Opio1, Paul Edward Okello1, Daniel Kadobera1; Affiliation: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program

Summary

In March 2017, we visited Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement in Kiryandongo District to ascertain the capacity for Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR). We selected six health facilities serving the refugee settlement and interviewed their In- charges. All the 6 health facilities serving the refugee settlement were well staffed above the norms. IDSR systems were in place in all facilities but poorly implemented. The major obstacles in disease surveillance were non-use of case investigation forms in reporting of priority diseases (50%), absence of standard case definition booklets (50%), and absence of updated HMIS forms and registers (67%). This was coupled with non-functionality of the District Epidemic Preparedness and Response Committee (DEPPRC). We recommended IDSR refresher trainings in cycles of two years and supply of IDSR guidelines to all facilities and DHTs. We also recommended regular support supervision of health facilities to strengthen IDSR activities, and strengthening of the DEPPRC and the district rap- id response team (DRRT).

Background

By March 2017, about 52,607 individuals were resettled in Kiryandongo Refugee and IDP camp. Most of these people were from South Sudan (51,884) and the rest from DRC (170), Kenya (161), Sudan (104), and 226 internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Uganda. Due to the existing humanitarian needs, many local and international organizations have responded to the emergency to improve on the welfare of the affected populations.

Like any emergency situation, Kiryandongo Refugee Settlement is vulnerable to disease outbreaks and seasonal peaks in malnutrition. An upsurge of measles, cholera, Hepatitis B, malaria, upper respiratory tract infections and diarrhoeal diseases have occurred on many occasions. The capacity of the district health system to detect, report, analyze, investigate, prepare and respond to these outbreaks and health threats had not been evaluated before.

We assessed the capacity of the District Epidemic Preparedness and Response Commit- tee (DEPPRC), the District Rapid Response Team (DRRT), Health Facility teams and Village Health Teams (VHTs) to conduct Integrated Disease Surveil- lance and Response (IDSR) in both the resettlement camp and the host community.

Methods

We selected five health facilities serving the refugee settlement out of the total of 24 health facilities serving the district and interviewed their In-charges and Surveillance Focal Persons. A sixth health facility serving the host community was included in the assessment. The six health facilities visited were: Kiryandongo Hospital, Panyadoli HCIII, Panyadoli Hills HCII, Katulikire HCIII, Nyakadot HCII, and Diika HCII.

Key informant interviews were conducted with DHT members including the District Surveillance Focal Person, Principal Nutrition Officer, and some members of the DRRT and DEPPRC. A consultative meeting was held with 80 VHTs and their focal persons to generate data on community surveillance. Data was collected electronically using Kobo Collect for Humanitarian Emergencies. Observation method was used for registers and reporting tools based on the following attributes: Simplicity, Flexibility, Accept- ability, Sensitivity, and Timeliness.

Findings

Human Resources capacity gaps affecting IDSR. A total of 7 out of 11 DHTs and 48 health facility staff were trained on IDSR in 2015. Most of the IDSR trained health workers have been absorbed in government service in other districts hence leaving a big skills gap in IDSR services in Kiryandongo District.

Only 70 out of 372 VHTs in the district were trained on integrated community case management (ICCM). Most of the VHTs were from the refugee and IDP settlement (60) and only 10 were from the host community near the settlement. The training mostly concentrated on case management. All health facilities serving the refugee and IDP populations are adequately staffed and in some cases the staffing levels exceed the government recommendations by far due to interventions by relief agencies.

Capacity of DHT to investigate and respond to Outbreaks

The DSFP acknowledged the occurrences of key diseases such as Bacterial Meningitis in Mutundwa Sub-county in the year 2012, and incidences of malnutrition both in the camp and host community. He also noted that the DHT was incapacitated to investigate and respond to some of the outbreaks.

Sensitivity of the surveillance system

The surveillance system was sensitive in detecting suspected outbreaks from the health facilities how- ever, all the cases listed below were not investigated by the DHT (Table1).

| Health Events Reported | Number of Cases |

| Malaria Cases | 88,746 |

| Typhoid Fever Cases | 575 |

| Dysentery Cases | 349 |

| Animal Bites (Suspected Rabies) Cases | 142 |

| Adverse Events Following Immunization Cases | 4 |

| Presumptive Multi Drug Resistance (MDR) TB Cases | 4 |

| Acute Flaccid Paralysis Cases | 2 |

| Measles Cases | 32 |

| Malaria Deaths | 30 |

| Perinatal Deaths | 9 |

| Maternal Deaths | 3 |

| Presumptive Multi Drug Resistance (MDR) TB Deaths |

1 |

Source: DHIS2, Ministry of Health, Uganda.

Simplicity and Flexibility of the surveillance system

Simplicity and acceptability were assessed using questions concerning compliance, ease of use, and number of steps in the system alongside users’ opinions on the appropriateness of IDSR in Detecting, Recording and re- porting of priority Diseases.

Detection of diseases

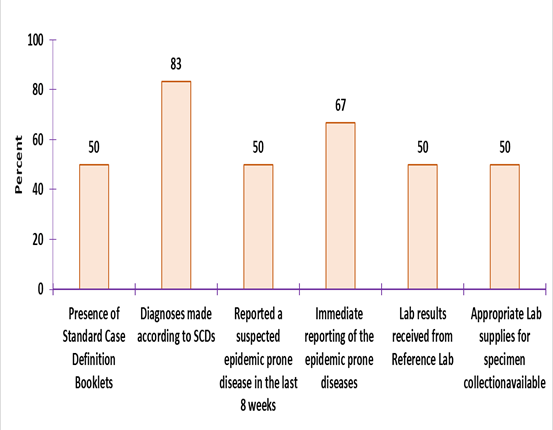

Diagnoses of priority diseases were made according to standard case definitions (SCDs) in 83% of the health facilities. No facility had drawn its list of priority diseases, events and conditions.

Figure 1: Functionality of the surveillance system to detect and report priority diseases

Acceptability and Timeliness of the surveillance system

The average weekly reporting rate in Kiryandongo District was 79% at the end of March 2017 (Week13). This is still below the national target of 100% implying low level of acceptability and use. Most of the poorly reporting facilities serve the refugee population. The DSFP attributed it to inadequate skills to record, summarize and send reports on mTrac reporting forms by the various section heads in the health centres. About 67% of the health facilities had missed submission of at least one weekly report in the last 8 weeks.

Data quality attributes

Completeness was assessed by looking at the filling of the registers and the reporting forms which translates into quality of records from which reports are generated. The register is poorly filled such that some of the key indicators like suspected cases of malaria; next of kin can- not be extracted easily. The poor filling of these registers is associated with the inadequate training of data clerks.

Capacity of health facilities for analysis and interpretation of data

Only 33% of the 6 health facilities assessed demonstrated the capacity to analyze and present data using charts and maps.

Functionality of DEPPRC and DRRT

Kiryandongo District has a non-functional Epidemic Preparedness and Response Committee (EPPRC). This committee was set up in the year 2015 by MoH but has not been performing their key functions. Several factors such as attrition of key members contributed to the non-functionality of this committee. Most of the members were not trained on IDSR. There is also no dedicated funding for this commit- tee hence limiting their sitting. The DRRT was functional with some supplies in stock. The Epidemic Preparedness and Response Plan is lacking.

Conclusions

Many relief agencies have supported the health team in Kiryandongo refugee settlement, and much has been done to attend to cases in the facilities by increasing staffing levels. It appears less work has been done to support disease surveillance, because IDSR reporting standards are sub- optimal in many health facilities.

Public Health Actions

We disseminated our findings to the DHT and partners and immediate actions for improving early detection and response to alerts and outbreaks were agreed upon. We conducted a training of the District Rapid Response Team, DEP- PRC and Health Partners on IDSR after which they were tasked to trained health facility staff on prompt case detection and reporting. We also prepared the DEPPR plan and shared with the DHT.

Recommendations

We recommended IDSR re- fresher trainings in cycles of two years and supply of IDSR guidelines to all facilities and to DHTs. The DEPRC and DRRT should be strengthened. Support supervision of health facilities should be improved.

Comments are closed.