Decline in Malaria Incidence in Tororo District, Uganda following implementation of Vector Control Interventions, 2013-2015

Authors: David Were Oguttu1, David Cyrus Okumu2, Patrick Omita2, Alex Ario Riolexus1; Affiliations: 1PHFP-FET, 2Tororo District Health Office

Summery

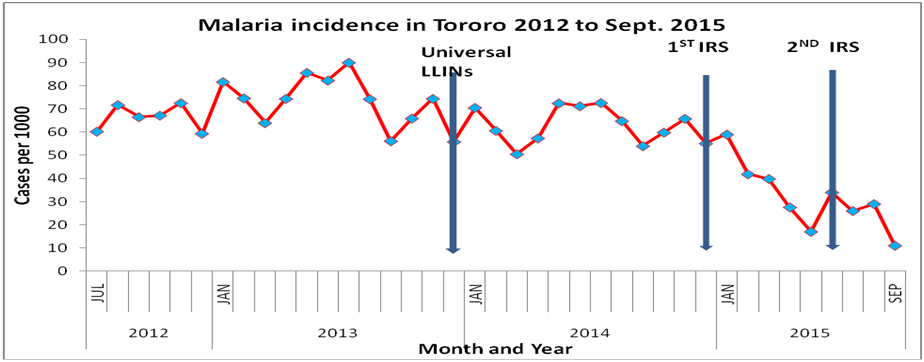

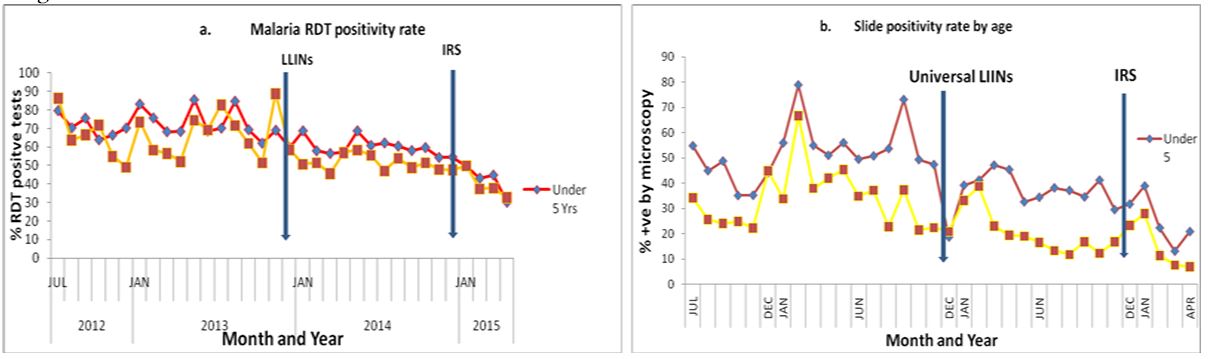

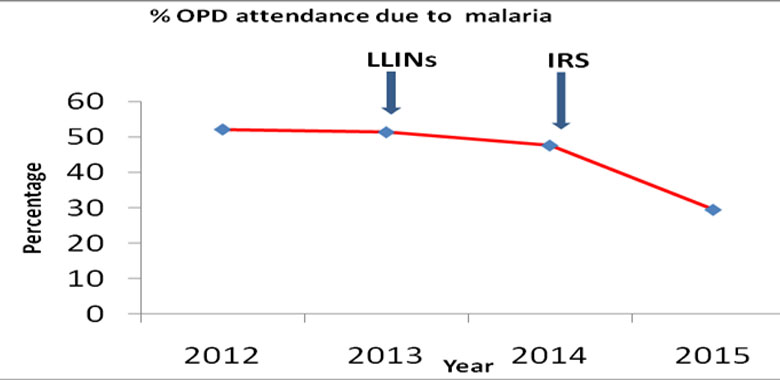

This article presents achievements in the ongoing malaria control in Tororo District following universal distribution of Long Lasting Insecticide treated Nets (LLINs) and introduction of Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS). We used routine District Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) surveillance data 2013-2015 to assess the extent to which malaria incidence changed after implementing vector control interventions. The peak of malaria incidence reduced from 90/1000 in July 2013 to 73/1000 in 2014 after Universal distribution of LLINs. Following introduction of IRS in December 2014, the peak of malaria incidence significantly reduced from 73/1000 in 2013 to 31/1000 in July 2015. Slide and Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) positivity rates have also reduced. OPD attendance due to malaria also declined during the same period.

Introduction

Tororo is one of the districts in Eastern Uganda whose geographical features and economic activities favor breeding of malaria vectors. Wetland rice growing is a major agricultural activity in all the 17 rural sub counties. Swamps along rivers and streams such as R. Malaba, Kanyinima, Aturukuku and Nyamatunga are the major areas of rice paddies. During high malaria transmission rainy months of the year (April-July), rice gardens become flooded and hold water for long periods providing potential breeding sites for Anopheles mosquitoes. Cattle kept in homes make hoof prints on wet grounds creating more Anopheles breeding sites closer to homes. In rural villages where mosquito breeding is high, most people live in grass thatched houses suitable for indoor resting and feeding of the vectors leading to high Plasmodium transmission. Entomological surveys of malaria vectors conducted before 2012 described Tororo to be second to Apac with a high population of Anopheles mosquitoes feeding and resting inside inhabited grass thatched houses with a biting density of 160 bites per person per night and a high annual entomological inoculation rate of 591/person/year (Okello, et al 2006).

In December 2013, the Ministry of Health ( MOH) conducted universal distribution of Long lasting insecticide treated nets in the district giving one net per two people in every household. Tororo is among the 14 districts where the National Malaria Control Programme start- ed implementing IRS in December 2014. In this study we describe the magnitude of malaria in Tororo 2012-2015 and assess if there was a change in the disease incidence following universal distribution of LLINs to communities and introduction of IRS. Our findings in- form the district, National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and partners on temporal change in clinical malaria burden following vector control interventions. We also demonstrate use of routine surveillance data in assessing malaria control interventions.

Methods

We analyzed aggregated district malaria surveillance data 2012 to 2015 from District Health Information System (HMIS) form 105. The data came from five hospitals, 3 health centre IV facilities, 18 health centre IIIs and 35 health centre II units. The number of malaria cases reported included both the laboratory and clinically diagnosed. rates and incidence by month.

We computed the percentage of malaria cases in Out Patient Department per year, malaria laboratory test pos- itivity rates and incidence by month. We used Chi square for trends to analyze the annual change in malaria incidence.

Results

The peak of malaria incidence reduced from 90/1000 in July 2013 to 73/1000 (P<0.05) in 2014 after universal distribution of LLINs. Following introduction of IRS in December 2014, the peak of malaria incidence fell to 31/1000 (P<0.05) in July 2015. After the second round of IRS the malaria incidence decline to below 20 cases per 1000 by September 2015

Laboratory test positivity rates have declines among the be- low 5 year old children and the above five individuals. RDT positivity fell from 68% in April 2015 to 30% among the under fives and 52 to 33 among the 5 & above (Figure 2.a). Micros- copy malaria slide positivity rate declined from 56% to 21% among the under fives and 45 to 7% among older individuals in the same period (Figure 2.b)

Discussion and recommendations

The study findings indicate that malaria incidence, test positivity rates and OPD attendance due to malaria are declining following implementation of vector control interventions (Figure 1). A small decrease in incidence after universal distribution of LLINs implies that the vector population could have remained high or net use to protect individuals from infective bites was poor. Following implementation of IRS the rapid decrease in malaria incidence could have been as a result of huge reduction in the vector density. There was sharper decline in incidence when IRS was introduced than when LLINs were used alone. This is similar to the effect of IRS reported by Steinhardt et al (2006) in Northern Uganda. With reducing malaria transmission, the human population in the district will gradually lose immunity and become very susceptible. It is therefore important to consider implementation of strategies to sustain the gains made against malaria to prevent the disease resurgence and resultant epidemics after halting IRS in the district.

Lack of reliable HMIS data for years earlier than 2012, limited our analysis to recent years. The study could not build a model to estimate the actual contribution of vector control interventions to the reduction in malaria incidence due to lack of data on other factors which also affect transmission. The estimated malaria incidence may not be very accurate because we used both reported confirmed and clinically diagnosed cases, but gives a true temporal situation of malaria to inform the program.

Malaria incidence, test positivity rates and the contribution of the disease to OPD attendance have declined significantly since introduction of vector control interventions. There is need to sustain the achieved success to avoid malaria resurgence and epidemics.

Figure 3:

Comments are closed.