A Cluster of Deaths due to Consumption of a Dead Pig, Kagadi District, Western Uganda, Nov 2016

Authors: L. Kwagonza1*, C. Kihembo1, B. Lubwama2, H. Kyobe Bosa1, F. Ocom3, G. Pimundu4 J. Ojwang5, Alex R. Ario1; Affiliation: 1 Public Health Fellowship Program -Field Epidemiology Training, 2 Epidemic Surveillance Division, 3 World Health Organization, 4 Central Public Health Laboratories, 5 Centres for Disease Control and Prevention.

Summary

On 3 November 20 12, three mysterious deaths occurred in the same household after consumption of a dead pig for lunch. We investigated this cluster of deaths to identify the cause of death and recommend prevention measures. We defined a suspect case as sudden onset of abdominal pain or vomiting from 1 November 2016 in a resident or visitor of Kisegu village and any one of the following symptoms: diarrhea, headache, body weakness and perceived fever. We identified 8 case-persons all from the same household. The attack rate was 80% and case fatality rate of 38%. The main symptoms included: Abdominal pain (100%), body weakness (75%) headache (50%), vomiting (25%), and (48%) diarrhea (50%) among others. All 8 cases shared a meal of meat from the dead pig and the first deaths occurred within 48 hours. The toxicology testing from the remains of the pig intestines showed traces of carbaryl and chlorfenvinphos. This cluster of deaths was caused by consumption of a dead pig intoxicated with a carbamate and organophosphate. We recommended stricter control of pesticides in the district and countrywide.

Introduction

On 7th /11/2016, Ministry of Health through EOC received an alert from the surveillance focal person of Kagadi District of two mysterious deaths from the same family. The family had butchered and feasted on a dead pig one day before symptom onset in the index and fatal case. The two brothers and their mother (fatal cases) had complained of severe abdominal pain, diarrhea, headache, general body pain, weakness and vomiting. Three other family members developed similar symptoms on 8th November 2016 except vomiting. Five samples from the isolated suspects tested PCR Negative for Viral hemorrhagic fevers. Based on the above information; a team comprising of MoH (ESD, CPHL and PHFP), WHO, CDC and Kagadi DHT set out to conduct an epidemiologic investigation to identify the cause, mode of transmission and recommend control measures for this outbreak.

Methods

Kagadi District is located in mid-western Uganda. We defined a suspected Case as sudden onset of abdominal pain or vomiting from 1 November 2016 in a resident or visitor of Kisegu village and any one of the following symptoms: diarrhea, headache, body weakness and perceived fever. The team visited the hospital where the survivors were admitted, the affected village and health facilities which managed the affected persons. We interviewed the survivors, persons at the home where the death occurred and village residents with vital information on the meat consumed by the case persons. The team reviewed records in the health facilities and line listed the cases. We held discussions with the village local leaders and village health teams in search of other cases and exhumed the pig’s intestines. Soil samples from the spot where the pig was slaughtered and underneath the spot where the intestines were buried were submitted to Government analytical research laboratory for toxicology investigations. The team also searched for evidence of pesticides, in and around the home including their farm- land and neighborhood. An assessment of the general wellbeing of the other pigs in the household and in the neighborhood was also done.

Results

Person distribution

A total of 8 cases from the same household with 3 deaths were identified, Case Fatality Rate = 37% (3/8). Apparently all the 10 household members consumed the pork though 8 were affected, attack rate 80% (8/10). Among females, the attack rate was 100%, while among males it was 75%.

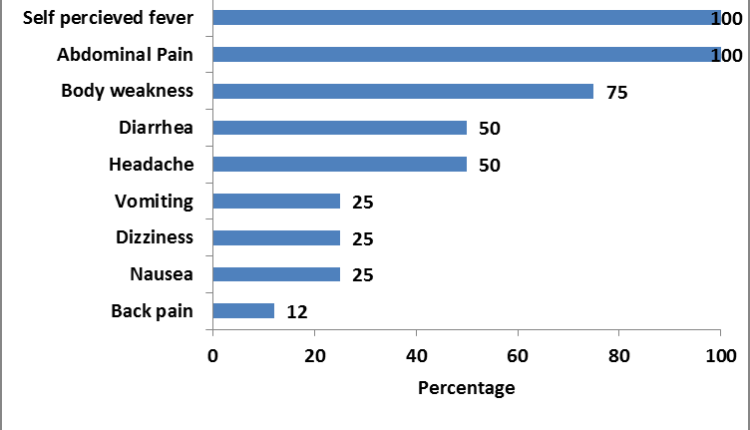

Distribution of symptoms

All the case patients presented with abdominal pain and self-perceived fever. However, no fever was documented in any of the survivors on admission to hospital.

Figure 1.0 Distribution of symptoms

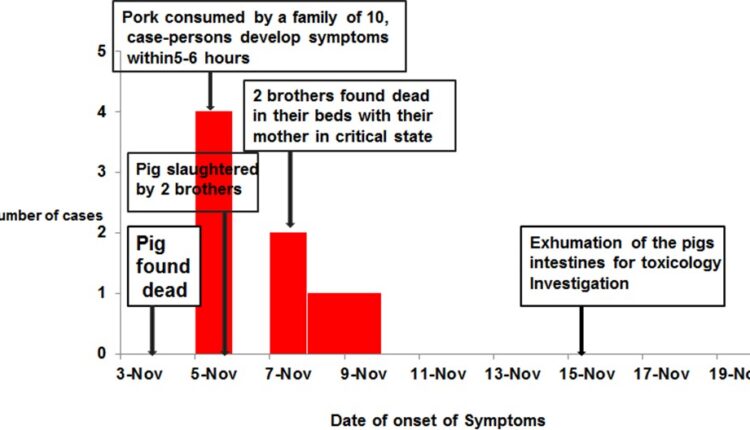

Timeline of events: The suspected pig died on 3rd and was slaughtered by the deceased brothers (26 yrs and 12 yrs) and roasted a pig on 4th November 2016. They roast- ed and ate the liver/lungs of the pig. A neighbor (actual owner of the pig) noted that the liver/lungs were “black” and the meat looked funny, hence declined taking a share of the meat. On 5th November 2016, with the help of their mother, the brothers completed the process of roasting and preparation of the meat for the family lunch. Nine of the family members consumed the pork for lunch between 12-2pm.

The 10th family member missed lunch as he was not available at the time of serving; however he ate his share in the evening. He later felt abdominal discomfort also fell ill. By dinner time (5-6 hours later), the two deceased brothers, their father and mother had started feeling unwell with abdominal pain, vomiting followed by diarrhea through 7th Nov 2016. They were dis- covered dead in their beds by their younger brother about 6am on Monday 8th Nov 2016. Their mother was found delirious by that time. The 3rd victim (mother) was admitted in a comatose state at a nearby clinic.

The epidemic curve showing onset of symptoms

Environmental Assessment: The family reported no use of pesticides and there was no evidence of use of such products in the household. However, a nine year old boy reported having seen the family members use unknown rat poison in the recent past.

Laboratory findings: Five samples from the isolated suspects tested PCR Negative VHFs, Anthrax, the toxicology report indicated presence of 0.0867 ppm Carbaryl and 0.1097ppm Chlorfenvinphos.

Discussion

This cluster of deaths was due to unintentional chemical poisoning from consumption of a dead pig contaminated with carbonates and organophosphates. The sudden deaths of the two brothers, their mother and symptom onset from the family members clearly demonstrate a dose response relationship.

The two brothers who died had a high exposure from slaughtering, and roasting and preparing the lunch meal as well as consumed the liver which we highly suspect to be toxic. They went ahead to have lunch thereby increasing on the exposure amounts. Usu- ally, the household takes a bigger share of the plate compared to other members of the household and in addition he ate some liver.

Discussion

This could explain why the four case–persons just described developed symptoms on the same day at different hours (first the 2 brothers, followed by their mother and then their father in that order).

In addition to this, the 9 year old boy who reportedly declined to eat the meat and the 3 year old who ate very little meat apparently did not develop any sign or symptom as exhibited by the rest of the household members.

Exposure to organophosphate or carbonates can occur through inhalation, skin contact, or ingestion. When this occurs, inhibition of Acetyl cholinesterase takes place resulting in disruption of the activities of the Central Nervous System at Neuromuscular junctions. This leads to accumulation of Acetyl choline hence overstimulation of muscles (Chaudhry, 1988).

Conclusion

This was a localised cluster of deaths was due to unintentional chemical poisoning from consumption of a dead pig contaminated with carbamates and organophosphates. All the affected people ate the pork and developed symptoms and signs consistent with organophosphate and carbamate poisoning soon afterwards.

Recommendations

We recommended stricter control of pesticides in the district and countrywide. We also recommended training of the District Health Teams on the importance of collecting adequate samples from the deceased for further investigations. The district Health officials should sensitize people about the importance of seeking early treatment in the event of unusual signs and symptoms appear to an individual.

Reference

Chaudhry, R., et al.,. (1988). A foodborne outbreak of organophosphate poisonin . BMJ, 313(311 3): p. 224–9.

Comments are closed.