Distribution of Tetanus in Uganda between 2012 and 2016

Authors: Joyce Nguna1, Benon Kwesiga1, Alex Riolexus Ario1, Affiliation: 1Uganda Public Health fellowship Program

Summary

Tetanus is a nervous system disorder characterized by muscle spasms caused by the toxin-producing anaerobe Clostridium tetani, which is found in soil. Uganda validated the elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNTE) in 2011. However, it has the highest reported rates of nonneonatal tetanus (Non-NT) worldwide. A cross- sectional descriptive analysis of tetanus data from 2012 to 2016 shows an incidence of 10/100,000 population with Non-NT contributing the highest proportion.

Kampala district recorded the highest incidence. A total of 1105 tetanus related deaths were recorded and majority due to Neonatal tetanus (NT). We recommend the scale up Tetanus toxoid (TT) vaccination for adult males and females and strengthen community-wide health education on the importance and benefits of TT for pregnant mothers in order to increase its utilization.

Introduction

Uganda validated the elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNTE) in 2011, however, it has the highest reported rates of Non-NT in the world [1] with a higher proportion of cases reported in women compared to men, which is unexpected as women receive tetanus booster doses during reproductive age and pregnancy. A three-dose primary series of pentavalent vaccine containing TT is provided to infants through routine immunization services at 6, 10, and 14 weeks of age [2].

Uganda does not provide the three WHO-recommended booster doses of TT containing vaccine (TTCV) at ages 12–23 months, 4–7 years, and 9–15 years. To prevent and maintain MNTE, up to five doses of TTCV are provided to women of reproductive age (WRA) [2]. High quality surveillance data is essential to monitor tetanus disease burden and guide national policy. We described the burden and mortality rates of tetanus as reported through HMIS and to provide recommendations to strength- en tetanus surveillance in Uganda.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive analysis of tetanus data reported through the Uganda HMIS between 2012 and 2016. Monthly and annual district level aggregated data on tetanus incidence was obtained from the District Health Information System (DHIS2) from 116 districts. Data was extracted by age (0–28 days, 1 month–4 years, and ≥5 years), sex, region and district. High reporting districts and health facilities with the highest cases were identified.

We extracted both regional and district data to obtain trends in NT and non-NT cases. Selected data was downloaded into Microsoft excel and exported to Epi-info version 7.2.0 for analysis. The 2014 National Census data was extrapolated using an annual growth rate of 3.03% to carryout descriptive analysis on person, place and time. Incidence was calculated per 100,000 persons and distribution of age and sex was calculated. Results were presented in tables and graphs and QGIS was used to map tetanus in the districts of Uganda.

Results

Tetanus was grouped into NT and Non-NT (over 28 days of age). A total of 17,903 cases were recorded with males (56.1%) and females (43.9%). Age category 5-59 years had the highest (83.5%) number of cases (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of tetanus cases in Uganda between 2012 and 2016

| Variable | Category | Frequency (%) |

| Gender | Male | 10027 (56.1) |

| Female | 7854 (43.9) | |

| Category | Neonatal | 1555 (8.7) |

| Non-neonatal | 16326 (91.3) | |

| Age group | 0-28 days | 90 (1.7) |

| 29 days-4 years | 74 (1.4) | |

| 5-59 years | 4346 (83.5) | |

| > 60 years | 693 (13.3) |

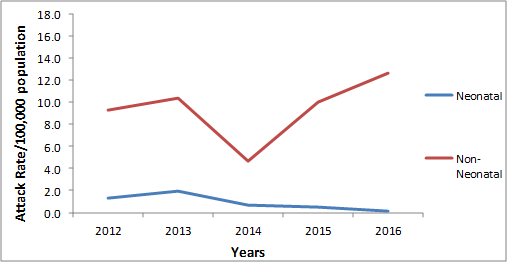

Incidence of Tetanus in Uganda between 2012 and 2016

The distribution of tetanus cases in Uganda has not been consistent for the five years under review but an increase in incidence was noted. Non-NT contributed the greatest proportion of tetanus cases with a high incidence of 12.7/100,000 in 2016.

A slight rise was not- ed in 2012 to 2013 in the NT cases which subsequently drop till 2016, while the Non-NT cases gradually increased from 2012 to 2013, declined sharply in 2014 before a sharp increase followed from 2015 to 2016 where the highest peaks were recorded (Figure 1).

Sex distribution of Non-NT cases between 2012 and 2016

Both males and females were affected, however males contributed the highest percentage of 50.8%.

| Year | Male

n (%) |

Female

n (%) |

Total |

| 2012 | 1400 (45.8) | 1658 (54.2) | 3058 |

| 2013 | 1574 (44.9) | 1934(55.1) | 3508 |

| 2014 | 1565 (45.0) | 1911(55.0) | 3476 |

| 2015 | 746 (44.7) | 922(55.3) | 1668 |

| 2016 | 3988(86.4) | 628(13.6) | 4616 |

| Total | 7273 (50.8) | 7053(49.2) | 14,326 |

Table 2: Sex distribution of Non-NT between 2012 and 2016

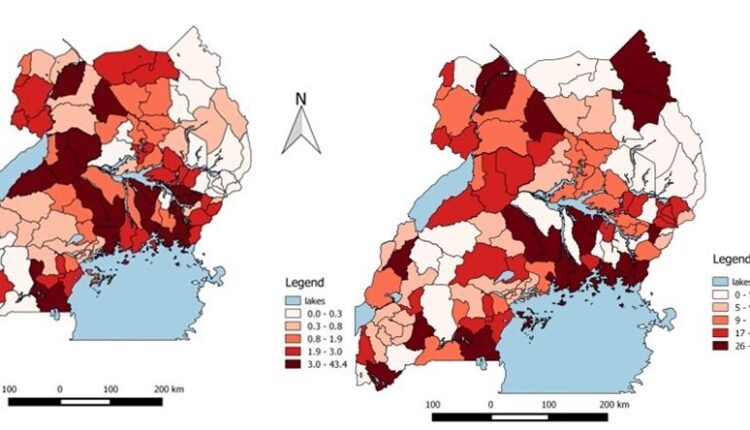

Distribution of Tetanus cases per district

Kampala reported the highest incidences for both NT and Non-NT. This was followed by Gulu for the NT and Kalangala for the Non-NT.

Mayuge District reported the highest number of tetanus related death followed by Kampala and Mbale Districts. Four of the districts that report- ed the highest numbers (Mbale, Mayuge, Jinja, Soroti and Kamuli) are from the Eastern region.

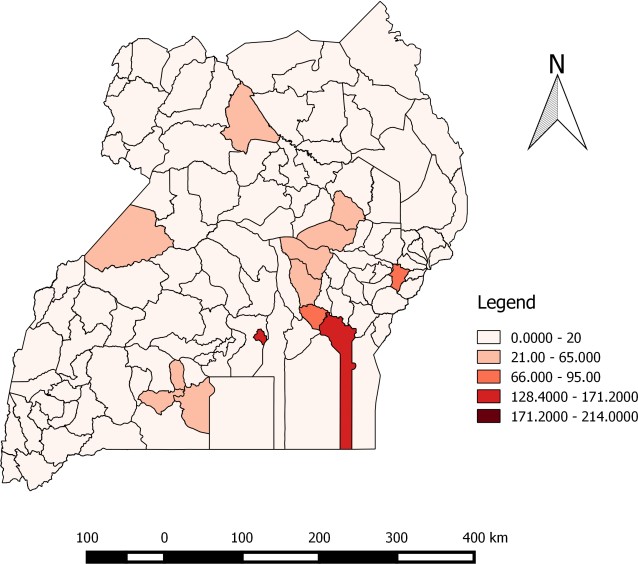

Health Facilities reporting the highest mortality between 2012 and 2016

Buluba Hospital in Mayuge district registered the highest numbers of Tetanus related deaths.

| District | Reporting facility | n | (%) |

| Mayuge | Buluba Hospital | 126 | 35.2 |

| Jinja | Jinja Hospital | 68 | 19.0 |

| Mbale | Mbale Hospital | 80 | 22.3 |

| Kampala | Mulago National Referral Hospital | 40 | 11.2 |

| Kamuli | Kamuli Missionary | 44 | 12.3 |

| Total | 358 | 100 |

Discussion

The shows existence of MNT (10.4/100,000 population per year) in Uganda despite it elimination in 2011. Nanteza, 2016 [3] found similar prevalence of 12% which is in line the study findings. Trend analysis for incidence rates showed the incidence of tetanus increasing per year between 2012 – 2016. Its still not clear if this high incidence depicts true increase in tetanus cases or data related issues like admissions of tetanus inpatients through the outpatients at the same facility, multiple OPD visits by the same patient, misdiagnosis or reporting errors. The highest percent- age of tetanus cases in Kampala could be that it hosts the National Referral Hospital and treats patients nationally.

Majority of the tetanus related death were attributed to NT cases and this is in agreement with Joy et al., 2005; Zupan, 2005 who implicated NT accounting for 38% of deaths in children younger than 5 years of age globally. Most non-NT cases were males who where not part of WHO’ focus on the elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus by 2015 which led to vaccination strategizing women of reproductive age and infants (Thwaites, 2015). Less attention however, has been given to the immunization of males after infancy. Reported high morbidities and mortalities seem over exaggerated, however there could be a lot of diagnostic differences, data capture and entry errors. Mbale and Mayuge had the highest mortalities being consistent with Nanteza, 2016 who reported similar districts as having high numbers of tetanus cases [3].

Recommendations

The government needs to refocus and scale up TT vaccination for adult males and females. Additionally, there is need for community-wide health education on the importance and benefits of TT for pregnant mothers in order to increase its acceptance and utilization.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Eradicating tetanus is possible and achievable using immunisation as the simplest and most cost effective way to reduce neonatal mortality rate. The government needs to refocus and scale up TT vaccination for adult males and females. Additionally, there is need for community- wide health education on the importance and benefits of TT for pregnant mothers in order to increase its acceptance and utilization.

References

1. Dalal, S., et al., Tetanus disease and deaths in men reveal need for Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2016. 94(8): p. 613.

2. WHO, , WHO vaccine-preventable diseases monitoring system. Global summary. WHO/IVB/2007, 2007.

3. Nanteza, B., et al., The burden of tetanus in Uganda. SpringerPlus, 5(1): p. 705.

4. Thwaites, C. and H. Loan, Eradication of tetanus. British medical bulletin, 116(1): p. 69.

5. Aliyu, A.A., et al., A 14 year review of neonatal tetanus at Ahmadu Bello University Teaching Hospital, Zaria, Northwest Nigeria. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology, 2017. 9(5): p. 99-

Comments are closed.