Suspected Cholera Outbreak associated with Drinking Unsafe River Water in Panyimur and Parombo Sub-counties, Nebbi District, March 2017

Authors: Eyu Patricia1, Kizito Suzan1, Nkonwa Innocent1, Alitubeera Phoebe1, Aceng Freda1, Nakanwagi Miriam1, Birungi Doreen1, Nguna Joyce1, Biribawa Claire1, Okethwangu Denis1, Opio Denis Nixon1, Benon Kwesiga1, Alex Riolexus Ario1 Affiliations; 1Public Health Fellowship Program-Field Epidemiology Track

Summary

On the 10th February 2017, Nebbi District Health Officer notified the Ministry of Health of a suspected cholera outbreak that had affected 117 people. We conducted an investigation to determine the scope of the outbreak, identify the mode of transmission and suggest control measures. We systematically identified cases using a standard case finding investigation form, conducted descriptive epidemiology and generated hypotheses. We conducted a case control study which included 67 cases and 134 controls. Drinking of unsafe river water from Nyaloi and Alala rivers was associated with the outbreak (OR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.2-4.1). We recommended treatment of drinking water and health education on safe drinking water, proper waste disposal and hygiene.

Introduction

On 10th February 2017, Ministry of Health received notification of a suspected cholera outbreak in Nebbi district, Uganda. The District Health Officer reported 117 suspected cases with 3 deaths. Nebbi district has suffered numerous outbreaks of cholera in the past few years and the most recent being in 2016.

Nebbi district is bordered by Lake Albert to the South and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) to the West (UBOS, 2016); this porous border with DRC facilitates spread and transmission of communicable diseases. The most affected sub-counties in this outbreak are Parombo and Panyimur, both of which border the DRC; and these communities’ main source of livelihood are fishing and farming.

Cholera is a communicable disease with a short incubation period of a few hours to 5 days and has a high epidemic potential. It is a bacterial infection caused by Vibrio Cholerae and is mainly transmitted through consumption of food, or water contaminated with the bacteria.

It commonly presents with profuse painless watery diarrhoea, and vomiting. When untreated, about 50% of the person cases die of severe dehydration (WHO, 2016) (Heymann, 2015). We conducted an investigation to determine the scope of the outbreak, identify the mode of transmission and recommend control measures.

Methods

We defined a suspect cholera case as sudden onset of profuse watery diarrhoea in a resident at least 2 years old from Parombo or Panyimur sub-county in Nebbi district, from 1st January 2017.

A confirmed case was a suspect case with Vibrio Cholerae isolated from stool by culture. Using a standardized case finding investigation form, we systematically searched for cases in the community with the help of the village health teams and updated the line list.

We carried out descriptive analysis and generated hypotheses. We tested these hypotheses using an unmatched case control study in which we randomly selected 2 asymptomatic village controls for each case identified giving a total of 67 cases and 134 controls.

We collected stool samples for laboratory confirmation of the outbreak and also carried out an environmental assessment of the various water sources and the community.

Results

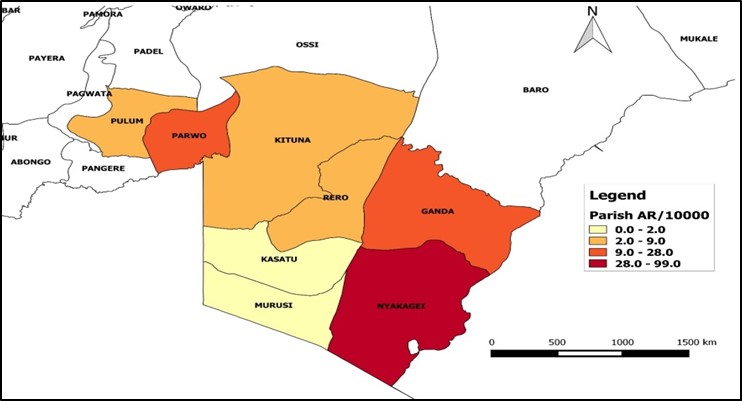

We identified a total of 222 suspected cases (103 females and 119 males). The median age was 17.5 years IQR: 6-35years. The most affected parishes were Nyakagei (Attack rate of 143/10,000) and Ganda (Attack rate of 21/10,000) in Panyimur sub-county and Parwo parish (Attack rate of 42/10,000 persons) in Parombo sub-county. (Figure 1)

Fig 1: Distribution of attack rates by parish

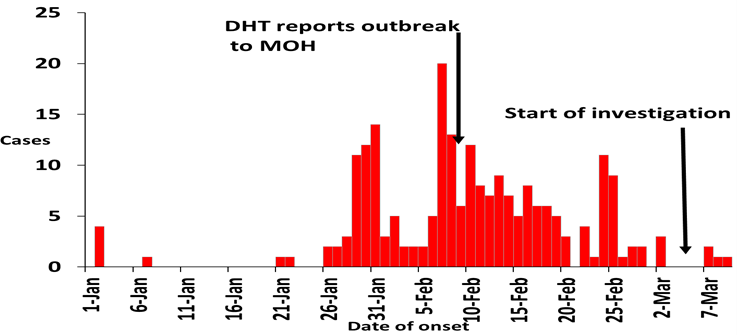

The index case had a date of onset of 21st January 2017. Majority of the cases were identified between the 27th January and 24th February 2017. (Figure 2)

Fig 2: Distribution of cases by date of onset of symptoms

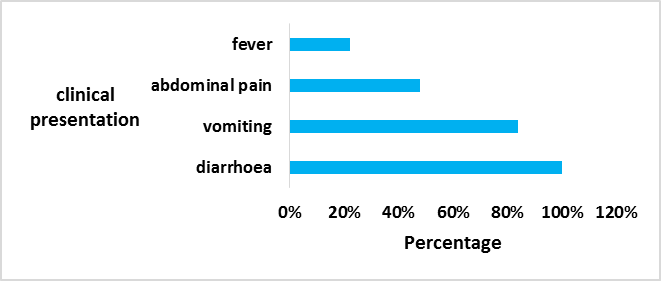

The clinical presentations were consistent with cholera as 100% of the cases

Fig 3: Distribution of symptoms

Environmental assessment

The water in the rivers was visibly dirty. The rivers are not protected so community members step directly in the river to collect water for household use, and also wash their clothes from the same river. There was open defecation ob- served in No Man’s land, Dei Parish in Panyimur sub-county. The dumping sites in some communities such as Market Square village in Parombo were poorly managed. There is a fairly good distribution of taps in Panyimur sub-county but some are not operational.

Case control findings: Case control findings

Stratified epidemic curves showed that the outbreak started in Nyakagei parish, Panyimur sub-county and spread to Parombo sub-county. 40/67 (60%) of cases compared to 56/134 (45%) of controls drank water from Alala and Nyaloi rivers (OR: 2.2, 95% CI: 1.2-4.1).

Discussion

Nebbi district has suffered numerous outbreaks of cholera in the past few years, and most have occurred in the dry sea- son as reported by the district leadership. The epidemiological findings and environmental assessment of this outbreak investigation were in line as most of the community members were drinking the river water which was visibly dirty. The findings of this investigation therefore suggested that consumption of river water was the risk factor for transmission of cholera in Nebbi district.

During the investigation it was noted that one of the community boreholes in Parombo sub-county was locked with a padlock by the wife of a traditional chief and out of respect for her, no one had questioned her actions. Because of this, the community resorted to using water from the nearby Alala River which was stagnant and visibly dirty.

The most affected sub-counties (Parombo and Panyimur) border the Democratic Republic of Congo. This could pose a risk of cross border transmission of the disease as cholera cases could cross over from the DRC to Uganda for treatment, trade or visiting family members and relatives thus propagating the disease.

This cross border transmission is in line with a cholera outbreak investigation done by Bwire et al in 2016 which showed rampant cross-border movements as one of the contributing factors of the cholera outbreak at the Uganda-DRC border (Bwire, et al., 2016). Furthermore, the No Man’s land on Uganda-DRC border has very poor sanitation as latrines were ob- served to have no pits therefore aiding open defecation by the communities in the No Man’s land.

Despite the fact that two months had already elapsed since cholera was suspected in Nebbi, new cases were still coming in from the community and the confirmation of the diagnosis has not been possible due to lack of transport medium. The 3 stool samples that were eventually collected were negative for Vibrio Cholerae. This could be because the cholera cases had taken antibiotics prior to going to the health facilities, and also RDT was not available to test for cholera.

Nebbi district is not yet able to contain the current infection and later on prevent new infections from happening. This was observed at the health facilities of the affected sub-counties which had a cholera treatment centre (CTC). These CTCs lacked infection prevention and control measures like having a barrier, the use of antiseptics, disinfectant for stepping in at the entrance, and protective gears.

The district health team raised a concern of always being insufficiently equipped and supplied with resources to enable them deal with such health emergencies. It was suggested that the MoH rethinks about providing buffer supplies to districts to help them manage outbreaks such as these. Also a case fatality rate of greater than 1/10,000 is an indicator of poor case management which is likely to lead to more cholera cases.

Conclusions and recommendations

This was a cholera outbreak that affected two sub-counties in Nebbi district. Drinking contaminated water from Ala- la and Nyaloi rivers was linked to the outbreak. The communities had poor sanitation and hygiene practices and case management was sub-optimal. The designated cholera treatment centers at the health facilities did not observe standard infection prevention and control measures. There was lack of timely laboratory testing of the samples.

We recommended treatment of drinking water by the community members; health education on safe drinking water, proper waste disposal and hygiene; the treatment centers should adhere to standard infection prevention and control practices; and continuous ac- tive surveillance especially in the most affected sub- counties.

References

- Bwire, G. et al., 2016. Cross-Border Cholera Outbreaks in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Mystery behind the silent Illness: What Needs to be Done?. 3 June.

- Heymann, D. L., 2015. Control of Communicable Dis- eases Manual, 20th Edition. 64th Edition ed. Washing- ton: American Public Health Association.

- UBOS, 2016. The National Population and Housing Census 2014, Kampala: Uganda Bureau of Statistics.

- WHO, 2016. Prevention and control of cholera out- breaks: WHO policy and recommendations, Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Comments are closed.