Mpox outbreak investigation at Sowe Island, Mukono District, Uganda, August–November 2024

Authors: Joanita Nalwanga1, Emmanuel Mfitundinda1, Dorothy Aanyu1, Benon Kwesiga1, Richard Migisha1, Lilian Bulage1, Alex Ndyabakira2, Alex Riolexus Ario1 Institutional affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Uganda, 2Directorate of Public Health and Environment, Kampala Capital City Authority, Kampala, Uganda Correspondence: jnalwanga@uniph.go.ug

Summary

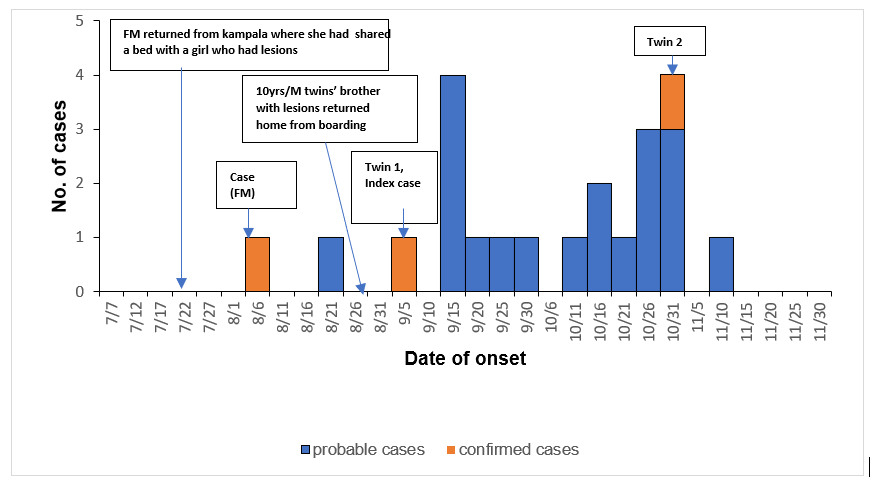

Background: On November 9, 2024, 1 year and 8 months old female twins residing at Sowe Island in Mukono District tested positive for mpox. Additionally, many other people presented with similar signs and symptoms at the island. We investigated to establish the magnitude of the outbreak, assess potential exposures, and to recommend evidence-based control and prevention measures.

Methods: We defined mpox cases as suspected, probable or confirmed cases using the standard case definition by the Ministry of health, Uganda and the World Health Organization. We collected samples from all suspected cases that presented with active mpox signs and symptoms. We conducted descriptive epidemiology of the cases and carried out an environmental analysis to understand the potential exposures to mpox.

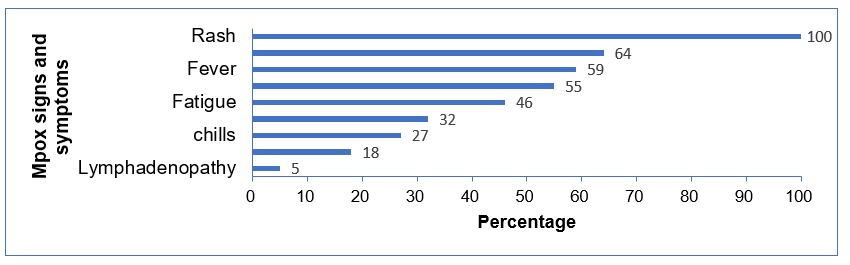

Results: There were 22 cases including 3 confirmed and 19 probable cases. All were children below 18 years, most were male 12 (55%) and the majority were aged between 5 to 18 years 19 (86%). The median age was 10 years (IQR 6-13). The majority were school going (86%) and attended universal primary school 12(55%). All cases presented with a skin rash, 64% had cough, 59% had fever, and headache (55%). Males (AR=8/100 persons) and children aged 5-18 years (7/100 persons) were the most affected. Transmission of the disease among cases was through day to day social interactions such as playing and sitting together at school or living in the same household.

Conclusion: This was an mpox outbreak among children possibly transmitted through daily interactions at school and at home. We recommended isolation and treatment of the confirmed cases by the Mukono District health team. Additionally, we recommended infection prevention practices such as hand washing, timely and continuous sensitization of the islanders on public health issues such as mpox in order to prevent future outbreaks.

Introduction

Mpox formerly known as Monkey pox is caused by an orthopoxvirus and spreads mainly through close contact with someone who has mpox (1,2). Mpox did not receive international attention until 2022 when it spread beyond the African continent (8,10,11). This led to its declaration as a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization (2,12). On July 24, 2024, Uganda confirmed its first cases of mpox reported in Kasese District (13). By November 2024, 649 cases had been registered across 45 districts in Uganda with Kampala, Nakasongola, Mukono, and Wakiso being the most affected (14). On November 9, 2024, twins aged 1.8 years old residing at Sowe Island in Mukono tested positive for mpox. Additionally, many other people presented with similar signs and symptoms at the island. We investigated to determine the magnitude of the outbreak, exposure risk factors, and recommend control and prevention measures.

Methods

Outbreak area

Sowe is a small island of approximately 64 acres of land on Lake Victoria, off the Mpatta subcounty mainland in Mukono District. The island has a dynamic population, an average of 500 people reaching as high as 700 during the busy fishing season. There are 2 primary schools (universal primary school and Crossway primary), both privately owned from nursery to primary six. There are no secondary schools or tertiary institutions. Fishing is the main source of income.

Case definitions and finding

We defined mpox cases as suspected, probable or confirmed cases using the standard case definition by the Ministry of health, Uganda and the World Health Organization. We line listed cases using the snowball method where individuals in the community with already existing symptoms led us to others. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the cases by age, sex and clinical presentation. We observed the housing, sanitation, health care services and economic activities of the residents of the Island. We collected samples from suspected cases with active signs and symptoms. The samples were shipped to the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) laboratory for PCR test.

Ethical considerations

The Ministry of Health authorized this investigation as a response to a public health emergency. The office of the Associate Director for Science at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Uganda, determined that this investigation did not involve human subject research and that its primary intent was public health practice. Additionally, we sought approval from Mukono District authorities to conduct the outbreak investigation. We obtained verbal informed consent from the respondents and ensured confidentiality by interviewing participants in privacy and keeping their data in a password protected computer accessed only by the investigating team.

Results

Descriptive epidemiology: We identified 22 cases, all were children below 18 years, mostly male, 12 (55%) and aged between 5 and 18 years, 19(86%). The median age was 10 years (IQR 6–13). The majority were school going, 19(86%) and attended universal primary school, 12(54%) (Table 1). The overall attack rate= 7/100. Males were the more affected (8/100) than females (6/100). Children ages 5–18 years were more affected (7/100) compared to children below 5 (4/100).

Table 1: Distribution of cases by gender, age group, and occupation during an outbreak of mpox, Sowe Island, Mukono District, Uganda, August–November, 2024

| Characteristic (n=22) | Frequency | (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 | (55) |

| Female | 10 | (45) |

| Median age (years) [IQR] | 10 | (6-13) |

| Age group (years) | ||

| <5 | 3 | (14) |

| 5-18 | 19 | (86) |

| Occupation | ||

| School going | 19 | (86) |

| Universal P/S | 12 | (54) |

| Crossway P/S | 7 | (32) |

| Non- school going | 3 | (14) |

All cases presented with a skin rash, some had cough (64%), fever (59%), and headache (55%) (Figure 2).

During our community case search, we identified Case CM (Figure 3) as one of the early cases that was still actively showing symptoms and whose sample turned positive. CM’s probable exposure was during her 3 days’ stay at a relatives’ place in Kampala where she shared a bed with another girl who had symptoms. On returning to the island, she noticed a body rash and embarked on self-medication. The disease possibly spread through the close interaction that people at island had especially children. The children at the Island played freely and entered each other’s home. The subsequent probable cases played together at school or sat next to each other in class. Twin1 was possibly exposed by her brother who returned from boarding school at the mainland Kampala, with lesions. The twins were observed being carried by older children who resided at the school. Twin 2 eventually got symptoms in October 2024 along with other children.

Discussion

All the cases were children. The disease was imported by those who had travelled to already affected districts on the mainland. The majority of the cases were male and school going. There were no severe cases or hospitalization.

Mpox spread on the island was only among children and given the overall attack rate, the disease was found not to be highly contagious among the children. This is similar to another study in France where children and adolescents had few secondary transmission of mpox (15). The majority of the affected children at the island were in school. The school setting is one of the drivers of community transmission of infectious diseases due to the close contact through activities such as playing that happen in schools (16). Though studies show low transmission rates in schools, school based interventions such as isolation of cases are believed to be instrumental in preventing and controlling community transmission of mpox (15,16). However, for the case of sowe island, transmission and recovery occurred with no major targeted interventions as the community went on with their usual life routines.

There was a possibility that undetected transmission occurred at island probably because of lack of awareness about the disease. It was noted that the disease had started in August and was only confirmed in November, 2024. This was similar to what was seen during the 2022 mpox global transmission where numerous transmission occurred and even recovered before being detected by health care authorities (17)

Study limitations

The outbreak happened on a small island where the team had to cross the lake on a daily basis with limited transportation options, this access restriction may have delayed response to the outbreak. Additionally, there was possible misclassification of cases as there were no health care facilities or qualified personnel to diagnose cases that had symptoms. The cases ended up healing without diagnoses and treatment.

Conclusion

The outbreak was likely imported to the island by individuals who came from the mainland areas of Kampala where there was an already existing mpox outbreak. The outbreak occurred only among children below 18 years, mostly males and those who attended the two schools located at the island. We recommended continuous case identification through the village health team at the Island in addition to regular sensitization of the occupants on public health issues. We recommended follow up on all confirmed cases and their evacuation to the treatment unit as they could potentially infect other people.

Public health actions

We conducted an mpox awareness meeting with the island’s local council leadership and encouraged them to guide the community to report any person with signs and symptoms.

Conflict of interest

None

Authors Contribution

JN, EM, DA and AN participated in the investigation. All authors contributed to the write up and review of the bulletin. JN wrote the drafts of the bulletin. BK, RM, LB, AN, ARA reviewed the bulletin and ensured scientific integrity.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program and Makerere University School of Public Health for technical support. We also acknowledge the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Uganda for funding the investigation. The Makindye Division surveillance team under Kampala capital city authority for carrying out the laboratory investigations.

Copyright and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin are in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- Mpox [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mpox

- Mpox outbreak [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/situations/mpox-outbreak

- Mpox [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mpox

- CDC. Mpox. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Signs and Symptoms of Mpox. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/signs-symptoms/index.html

- Mitjà O, Ogoina D, Titanji BK, Galvan C, Muyembe JJ, Marks M, et al. Monkeypox. The Lancet. 2023 Jan 7;401(10370):60–74.

- Mpox [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/mpox

- Marennikova SS, Šeluhina EM, Mal’ceva NN, Čimiškjan KL, Macevič GR. Isolation and properties of the causal agent of a new variola-like disease (monkeypox) in man. Bull World Health Organ. 1972;46(5):599–611.

- WHO. Mpox (monkeypox) – Democratic Republic of the Congo [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON493

- Clade I Mpox in Central and Eastern Africa – Level 2 – Practice Enhanced Precautions – Travel Health Notices | Travelers’ Health | CDC [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 10]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/level2/clade-1-mpox-central-eastern-africa

- Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, Rockstroh J, Antinori A, Harrison LB, et al. Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans across 16 Countries — April–June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022 Aug 24;387(8):679–91.

- Cevik M, Tomori O, Mbala P, Scagliarini A, Petersen E, Low N, et al. The 2023 – 2024 multi-source mpox outbreaks of Clade I MPXV in sub-Saharan Africa: Alarm bell for Africa and the World. Int J Infect Dis [Internet]. 2024 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Dec 4];146. Available from: https://www.ijidonline.com/article/S1201-9712(24)00230-3/fulltext

- WHO Director-General declares mpox outbreak a public health emergency of international concern [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern

- Uganda Mpox Situation report #002 | OMS | Escritório Regional para a África [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 24]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/publication/uganda-mpox-situation-report-002

- Mpox Outbreak in Uganda Situation Update – 22 November 2024 | WHO | Regional Office for Africa [Internet]. [cited 2024 Dec 4]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/uganda/publication/mpox-outbreak-uganda-situation-update-22-november-2024

- Reques L, Mercuriali L, Silué Y, Chazelle E, Spaccaferri G, Velter A, et al. Mpox in children and adolescents and contact follow-up in school settings in greater Paris, France, May 2022 to July 2023. Eurosurveillance. 2024 May 23;29(21):2300555.

- Amzat J, Kanmodi KK, Aminu K, Egbedina EA. School-based interventions on Mpox: A scoping review. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6(6):e1334.

- Paredes MI, Ahmed N, Figgins M, Colizza V, Lemey P, McCrone JT, et al. Underdetected dispersal and extensive local transmission drove the 2022 mpox epidemic. Cell. 2024 Mar 14;187(6):1374-1386.e13.

Comments are closed.