Exposure at crowded health centers, vaccine failure and failure to vaccinate as risk factors for measles transmission in Kamwenge district, Western Uganda, April to August 2015

Authors: Fred Nsubuga, Lillian Bulage, Alex Riolexus Ario - PHFP Field Epidemiology Track

Introduction

On 27 April 2015, a measles outbreak was confirmed in Kamwenge District, Western Uganda. We conducted an investigation to identify risk factors for measles transmission, estimate vaccination coverage, determine vaccine effectiveness. We defined a probable case as onset of fever and generalized rash with ≥1 of the following: Coryza, conjunctivitis, or cough; a confirmed case was a probable case with serum positivity of measles-specific IgM. We found cases by reviewing patient records and examining patients in patients’ homes.

We conducted a case-control study involving 50 cases and 200 controls, matched by village and age. We estimated the vaccination coverage based on the proportion of the controls vaccinated. By 30thAugust 2015, 213 probable cases had been line-listed. Of three affected sub-counties, Biguli had highest attack rate (38/10000); children ≤5 years had highest attack rate (9.2/10000).

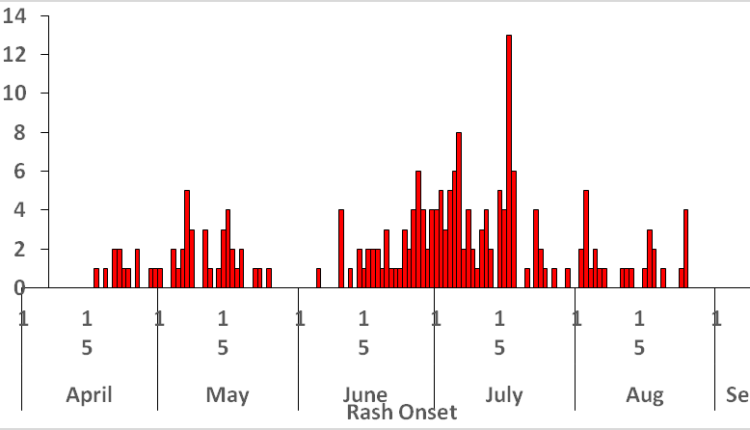

The epidemic curve showed sustained community transmission. 42% (21/50) of cases and 12% (23/200) of controls visited health centers during the case-patients’ likely exposure period (adjusted ORM-H=6.1; 95% CI=2.7-14). The estimated vaccination coverage ≤2 years in control persons was 58% (95% CI: 47-68) and the vaccine effectiveness was 80% (95% CI 35-94%). All health centers were very

crowded; no patient triage system was in place. Exposure to measles patients at health centers, low vaccination coverage and suboptimal vaccine effectiveness facilitated the spread of measles. We recommended emergency immunization campaign targeting children ≤5 years in the district, triaging and isolating febrile or rash patients at health centers and introduction of 2nd dose of measles vaccine in immunization schedule.

Methods

We defined a probable case as onset of fever and generalized rash with at least any of the following: Coryza, red eyes or cough. Confirmed case as a probable case with IgM positive. We visited health facilities (Rwamwanja HCIII and Biguli HCIII) within the affected county (Kibale) in order to update the line list. We reviewed patient records from 1st March 2015 to identify suspected cases based on the standard case definition (SCD).

Other health facilities and Village Health Team members were also sensitized about case finding using the Standard Case Definition. During hypotheses generation the team interviewed 24 suspected cases found at the health facilities and surrounding communities. The key variables explored were; visit to health facilities, church, trip to any place, going to school and attending any vaccination campaign/vaccination within the last 21 days before onset of rash.

By the end of the first day of case finding, the team identified 3 major factors that could be driving the outbreak namely; going to school, health facilities and attending church. A case control study was conducted to test the hypothesis. It involved 50 cases and 200 controls (Ratio; 1:4) matched by village and age. Only probable and laboratory confirmed cases were used in this study. Cases were identified with the help of a Village Health Team member, LC 1 chairperson or a village guide. After locating and interviewing a case, 4 controls from the same village with the same age as the case were conveniently selected and interviewed. We estimated measles vaccine coverage (VC) for children aged ≤ 1 year using control-persons. We estimated vaccine effectiveness (VE) using:

VE = 1- RR

≈ 1- OR

Where: VE = Vaccine effectiveness, RR= Relative risk of vaccinated vs. unvaccinated OR= Odds ratio (In rare disease OR ≈ RR)

Results

By August 2015, 213 probable cases had been line-listed in10 parishes of the 3 affected sub-counties. Measles-specific IgM was positive in 61 %( 14/23) of the blood samples collected. Of the 3 affected sub-counties, Biguli sub-county had the highest attack rate (3.1/1000); children aged ≤5 years had the highest attack rate of all age groups (9.2/10,000).

The median age of the cases

was 5.0, range 0.5-44 years. The epidemic curve showed sustained community transmission. 42% (21/50) of cases and 12% (23/177) of controls visited the health centers during the case-patients likely exposure period (ORM-H=6.1; 95% CI=2.7-14). The estimated vaccination coverage ≤ 2 year was 58% (95% CI=47-68%), the vaccine effectiveness was 81% (95% CI=35-94%).

Discussion

Since the beginning of 2015, there has been an increase in the number of measles cases in Uganda especially in the West and central region (DHIS2, 2015). It is therefore important to identify the risk factors, vaccine effectiveness and vaccination coverage so that effective control strategies can be implemented(1). Our findings suggested that visiting health centers was the most

important risk factor for measles transmission in Kamwenge District.

Inspection of health centers revealed extremely crowded conditions, making it very easy for measles probably the most infectious of all infectious diseases (2) to transmit among patients in the waiting area. This is in line with another study done in DeKalb County, Georgia Atlanta, where an outbreak occurred in a pediatric office setting and three of the children infected were never in contact with the source patient, suggesting airborne transmission (3).

It’s also in line with the study done in Sanliurfa Province, Turkey, which demonstrated Hospital exposure as risk factor for measles transmission (4). Health care settings have been known to be critical in the transmission of measles and generation of cases (5). This happens because large numbers of patients congregate in proximity with susceptible individuals and often for long period of time. The vaccination coverage estimated in this study was not consistent with the administrative coverage of the District.

The proportion of population vaccinated was low to confer population protection (6). However even in countries which have attained good immunization coverage, measles outbreaks are not uncommon (7). This finding is consistent with a study done in the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) is a South Pacific nation, where the measles outbreak lasted 6 months (8). WHO region where Uganda is; set its measles elimination goal in 2020. However elimination can only be achieved if measles coverage in every district is 95% (6).Measles vaccine effectiveness was low; a single dose of measles vaccine given at 9 months reduced the risk of measles disease by 81%. This is lower than the estimated measles vaccine effectiveness in the Africa region when the vaccine is administered at 9 months of age (9).

Vaccine effectiveness can be increased if a second dose of measles is administered at 12 months of more (10). In Uganda this is achieved during supplemental immunization activities (SIAs). If this is well done, and we improve routine immunization coverage, we can eliminate indigenous measles transmission.

Recommendation

We recommend an emergency immunization campaign targeting children aged <5 years in the affected sub- counties, triaging and isolating all febrile or rash patients at outpatient departments, and exclusion of all persons with a febrile or rash illness from social gatherings.

Comments are closed.