Evaluation of the Surveillance System in Adjumani Refugee Settlements, Uganda, April 2017

Authors: Innocent H. Nkonwa1, Emily Atuheire1, Benon Kwesiga1, Dinah Nakiganda2, Daniel Kadobera1, Alex Riolexus. Ario1; Affiliations: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, 2Ministry of Health Reproductive Health Division

Summary

Adjumani was one of the first districts to receive and resettle refugees since the onset of the South Sudan conflict in December 2013 and is currently hosting 201,400 refugees. The refugees are vulnerable to disease outbreaks and seasonal peaks of malnutrition. We conducted an evaluation of the surveillance system in Adjumani Refugee Settlements to identify the system strengths and weaknesses and recommend improvement measures. We determined attributes of the surveillance system using US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for public health surveillance as a reference.

Introduction

Adjumani Refugee Settlement in West Nile was one of the first to receive and resettle refugees from South Sudan since the onset of the conflict in December 2013. Presently, it has a total of 201,400 Refugees. This makes the district vulnerable to disease out breaks and seasonal peaks of malnutrition. For instance, since the start of the emergency, the refugee operations have had to deal with a measles outbreak in January 2014, the cholera outbreaks in 2015 and 2016 and cases of hepatitis B. We evaluated the public health surveil- lance system to determine if the diseases are being monitored efficiently and effectively (8). Every surveillance system should be evaluated periodically with recommendations to improve surveillance system usefulness, quality and efficiency (8),(9).

Methods

Study population: This evaluation was conducted among refugees in five settlements in Adjumani District. The participants from these settlements were health workers who were identified purposively. We interviewed surveillance focal persons and health facility in-charges.

Data collection and management: We conducted face to face interviews to collect information regarding the surveillance attributes i.e. reporting, tools, and data analysis using a semi structured questionnaire. We adapted CDC guidelines for evaluation of syndromic surveillance system to evaluate the system. Data cleaning and aggregation was done using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Description of the Evaluated system

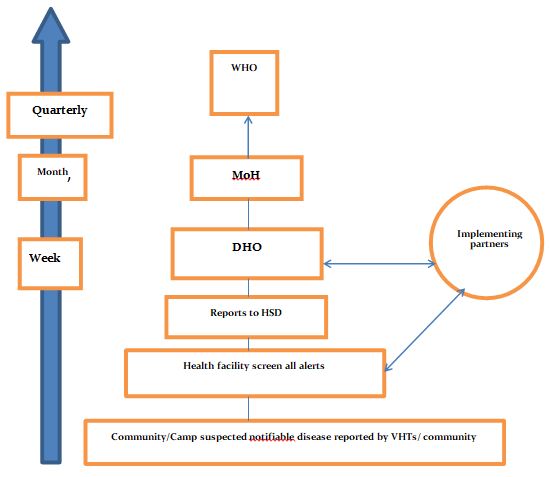

Adjumani District uses the paper-based Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) system (11) where forms are used to collect data at community and health facility levels and then sent to the District Biostatistician. The district Biostatistician validates, cleans and approves the data before submission to the Ministry of Health (MoH)

At all levels, respondents were conversant with the flow of information. However, this was mainly adhered to by the government supported facilities The implementing partners supported sites had another parallel system of reporting and were defaulting on reporting to the ministry of health Uganda recommended system. All the health workers reported lack of feedback from their superiors

Table 1: Epidemic preparedness measures in Adjumani District, April 2017

| MEASURE OF PREPAREDNESS | RESULTS |

| Presence of DEPPR | Yes, but non functional |

| Presence of comprehensive EPPR plans) | No |

| Availability of reporting tools | Yes |

| Buffer stock of essential medicines and health supplies | No |

| Presence of laboratory designated

for case confirmation |

Yes |

| Health DRRT trained on IDSR | Yes, preparing for previous outbreak |

| Community mobilization & sensitization activities implemented | Yes, mainly by implementing partners |

The district EPPR was present though found to be functional during times of outbreaks and disaster only. The case investigation forms were at the district level and lower facilities could only get them in case of suspected cases.

Table2: Capacity of health facilities for analysis, interpretation, confirmation, and investigation of reported cases of epidemic prone diseases in Adjumani refugee settlements April 2017

| Data analysis and interpretation | Drawing of graphs on priority | 50% |

| Display information on priority diseases |

0.0% |

|

| Reported a suspected epidemic

prone disease in the last 8 weeks |

17% | |

| Laboratory results received from

Reference Laboratories |

100% | |

| Health facility has Surveillance

Focal Person |

50% | |

| At least one staff at health facility

trained in IDSR |

50% | |

| Feedback | Health facility provides feedback to

the community through VHTs |

33% |

| Health facility receives feedback

from district |

00% | |

| Weekly reports sent on time | 36% | |

| Epidemic preparedness | Knows how to estimate supplies in emergency situations | 0.0% |

| District leaders conducted supervisory visits | 33% |

Most of the health facilities had poor indices for IDSR indicators. There was no health facility that displayed information on priority diseases. All health facilities were ill prepared to handle emerging epidemics. There were no supplies for responding to epidemics and none of the facilities had capacity to estimate supplies for emergencies. Feedback mechanisms were found to be very poor from the district and national level.

Attributes of the surveillance system for Adjumani District Timeliness

| Name of health facilities | Timeliness of the

reports = 100* T/N |

Completeness of

reporting = 100 |

| Adjumani Hospital | 61.5 | 100 |

| Mungula HCIV | 53.8 | 69.2 |

| Bira HCIII | 84.6 | 100 |

| Lewa HCII | 61.5 | 100 |

| Ayilo HCII | 0 | 0 |

| Ayilo HCII | 30.8 | 53.8 |

| Pagirinya HCII | 0 | 0 |

| Pagirinya HCIII | 0 | 0 |

Table 3: Timeliness for the facilities serving the Adjumani refugee settlements sampled for the first 12 Epi weeks 2017

Simplicity

The system was found to be complicated in the structure as many of the health workers were not even aware of the standard case definitions. The case investigation forms were not readily available and one had to consult the DHOs office in case of suspected epidemic prone condition. This was more evident among the non-government facilities.

Flexibility

The system had failed to integrate the HIS with the recommended HMIS which offered immense challenges to the service providers majorly in the partner supported sites.

Acceptability

The health workers were willing to use the HMIS system. The non government supported sites had a parallel structure through the HIS.

Data quality

The reported formats in some of the non-government facilities were different which generally affected data quality.

Stability

The system was found to be unstable majorly because most health facilities were using the manual system to generate and store data (i.e., paper based). It was difficult to trace some reports in most health facilities. It was also found that the funding for surveillance activities was lacking in all facilities, with funds only being availed after outbreaks are confirmed.

Representativenes and completeness

50% of facilities assessed consistently reported in their monthly and weekly reports on the reportable diseases.

Conclusions

Adjumani District has a DRRT which is activated during outbreaks. The District Epidemic Preparedness and Response Committee (DEPPRC), were constituted but non-functional. The non-functionality of the structures impeded implementation of epidemic prevention, preparedness and response measures.

Village Health Teams (VHTs) conducted Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) in the Adjumani resettlement camps and were the link to the communities. The non-government facilities had a parallel reporting structure which affected disease surveillance and response.

The reporting rates for most facilities was poor with government facilities (i.e., Adjumani hospital, Mungula HCIV, Biira HCIII, Lewa HCII) having

late reporting and most of the NGO facilities were not reporting at all.

Recommendations

1. Need to harmonize the HIS and HMIS reporting systems in the district and appropriate tools availed accordingly by the DHO2.

2. Need to avail the case investigation tools, case definition booklets and charts, standard tools to all facilities both government and non-government.

3. The district health office should have a contingency plan in case of epidemics.

References

1. Toole MJ, Waldman RJ. The public health aspects of complex emergencies and refugee situations. Annu Rev Public Health [Internet]. 1997

[cited 2017 Sep 14];18(1):283–312. Available from: http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.283

2. Yayi A, Laing V, Govule P, Onzima RAD, Ayiko R. Performance of Epidemic Prevention, Preparedness and Response in West Nile Region,

Uganda. [cited 2017 Sep 14]; Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Philip_Govule/publication/280938905_Performance_of_Epidemic_Prevention_Preparedness_and_Response_in_West_Nile_Region_Uganda/links/55cd0d9e08ae1141f6b9ebc5.pdf

3. Control C for D, Prevention (CDC, others. Assessment of infectious disease surveillance–Uganda, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep

[Internet]. 2000 [cited 2017 Sep 14];49(30):687. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10947057

Comments are closed.