Cholera outbreak caused by drinking lake water contaminated by sewage in Kaiso, Hoima district.

Authors: David Were Oguttu1*, Allen Okullo, Alex Riolexus Ario; Affiliation: Public Health Fellowship Program

Summary: This article presents a well investigated cholera outbreak which was controlled following recommendations based on field epidemiological evidence. In October 2015, a cholera outbreak was reported in Kaiso fishing village in Hoima district. The district responded by conducting mass sensitization and setting up a cholera treatment center in the village. The response reduced the number of cases, but the outbreak persisted until thorough outbreak investigation was done by field epidemiologists to identify the source of transmission. From a case control study and environmental assessment, drinking lake water contaminated by human feces from a gully channel after heavy rainfall ensued a point source outbreak. Following our evidence based epidemiological recommendations treatment of drinking water was done in households to stop the outbreak. We also recommended fixing of the piped water system which had broken down and construction of pit latrines as measures to prevent future cholera outbreaks in Kaiso

Introduction: Cholera is an epidemic potential diarrheal dis- ease caused by gram negative bacteria, Vibrio cholerae. The pathogen produces a toxin which causes severe loss of water in patients [1, 2]. . Each year cholera outbreaks occur in Uganda with annual average of 11,000 cases and 60-182 deaths. Rural areas of Uganda particularly areas neighboring the Democratic Republic of Congo are prone to cholera outbreaks because of interaction of people from different traditional settings with diverse hygiene and sanitation practices [3]. Lake side areas have been described to be hot spots of cholera epidemics during heavy rainfall compared to others areas. Generic public health actions are frequently used in cholera epidemic responses without detailed field investigations to address the source and mode of transmission. This could partly explain why cholera outbreaks have occurred repeatedly in the same areas.

In this article, we report a case where field investigation of a cholera outbreak generated evidence based recommendations that promptly controlled the outbreak.

On 12th October2015, the District Health Officer Hoima district reported an outbreak of cholera in Kaiso fishing village, located on the shoreline of Lake Albert. The disease had killed 2 people and many others. The district and the Ministry of Health responded by setting up a cholera treatment center (CTC) in the village and sensitizing the community.

Despite three weeks of the response, the number of cholera cases continued to increase till over 120 cases were reported and the outbreak persisted.

We conducted an epidemiological investigation to identify the source and mode of trans- mission in order to recommend evidence-based interventions to stop the outbreak.

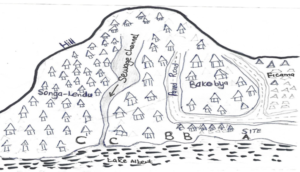

Methods: Kaiso village is located in Buseruka Sub-county on the shoreline of Lake Albert, Hoima district. The village is made up of three zones, Fichama, Songa-Bakobya and Songa-Lendu. The major tribal groups are the Bagegere, Bakobya, Alur, Banyoro, Ba- gungu and Congolese tribes. The village has estimated population of 9000 people. Songa-Lendu has a population of 6500, Songa-Bakobya 2000 and Fichama 500.The major economic activities are fishing and casual businesses. The village settlement has a sloping landscape extending from the escarpment of the western rift valley to the shoreline of Lake Albert. Latrine coverage in the village is low (10%), hence open defecation is a common practice.

We defined a suspected case as onset of acute watery diarrhoea in a resident of Kaiso Village from 1st October 2015 onward; a con- firmed case was a suspected case with Vibrio cholerae isolated from stool. We line listed a total of 122 cases from the Cholera treatment center and community. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the updated line list to characterize the

outbreak by person, place and time. Out of the 122 cases line listed, we obtained information from 80 who were present in the village by then. We obtained rainfall data from Kabwoya wildlife reserve weather station Located 2 km from Kaiso village.From findings of descriptive epidemiology, we generated a hypothesis that drinking untreated lake water was the source of the outbreak.

We carried out a case control study in which we inter- viewed 60 cases (aged 5 years and above) and 124 village controls using a structured questionnaire to test our hypothesis. Controls were residents of Kaiso village without acute watery diarrhoea within the same period of our case definition. We asked cases and controls questions on the sources of drinking water and history of boiling or treatment of water prior to the outbreak .

We inspected shore line water collection sites in the three zones of the village to assess possible sources of contamination. We also observed practices of human fecal disposal in the village, alternative sources of water and latrine coverage.

Results: By 2nd November 2015 22 cholera cases had been registered with 2 deaths (CFR= 1.6%). The epicurve showed a point source epidemic which started following heavy rainfall and reached its peak on 13th October (Figure 1).

One death occurred on 2nd and another on 10th October. Heavy rainfall washed feces from open defecation area in a gully channel during this period resulting into a point source outbreak in the community. On 12th October a cholera treatment center was set up in the village. On 14th October chlorine was distributed to households to treat drinking water after which a decline in the number of cases was noted.

Of the 3 villages, Songa-Bakobya was the most affected (attack rate = 18/1000) compared to 4/1000 in Fichama.

Case control study Findings: People who collected water from

Songa-Lendu (Site C) were seven times more likely to get cholera compared to those who collected water from the Lake res- cue site A. Drinking un-boiled water was associated with cholera. People who drank untreated water were more likely to get cholera compared to those who drank boiled water (Table 3).These findings supported the hypothesis that drinking contaminated lakeshore water was the mode of the cholera trans- mission in the outbreak.

Environmental assessment findings:

We found three major water collection sites (A,B, &C) along the shoreline as shown in figure 2. Site A (Lake rescue) is protected from water runoff contaminants by a paved road which lies parallel to the shoreline as illustrated in figure 2.People from Ficama zone collected water from site A. Site B was partially protected by a paved portion of the road while site C was a point where feces from open defecation area was discharged into the lake through a gully channel. This was a water collection site for people of Songa-Lendu and part of Songa-Bakobya. Open defecation was common along the gully channel because of lack of pit latrines in most households. The piped water system in the village had been vandalized six months earlier forcing the community to depend on the Lake as the primary source of water.

Discussion: Our investigation found a point source outbreak which occurred after rainfall washed human feces from a hillside

open defecation area into the Lake shore water in Kaiso village. Attack rate was higher in Son-

ga-Lendu and Bakobya villages in Fichama zone. Cholera transmission occurred through drinking untreated Lake water

Higher cholera attack rates in Songa-Lendu and Songa-Bakobya were due to proximity of the villages to the contaminated water collection site. Most people from these two zones collected their water for domestic use from site C. People living in Ficama zone collected water from the lake rescue site (A) which is close to them. The oil exploration company constructed a paved road between the residential area of the village zone and the shoreline. This protects the site from contamination by materials carried by erosion from residential and open defecation areas hence the lower attack rate in Ficama than the other two zones. Both children and adults were affected in this this outbreak.

Conclusion: This cholera outbreak was caused by drinking lakeshore water contaminated by human faeces washed down a gully channel after heavy rainfall.

Recommendations: We recommended provision of safe drinking water through; provision of water treatment tablets and boiling drinking water; repairing and protecting the vandalized piped water system by district authorities; and safe disposal of human waste. Higher cholera attack rates in Songa-Lendu and Songa-Bakobya were due to proximity of the villages to the contaminated water collection site. Most people from these two zones collected their water for domestic use from site C. People living in Ficama zone collected water from the lake rescue site (A) which is close to them. The oil exploration company constructed a paved road between the residential area of the village zone and the shoreline. This protects the site from contamination by materials carried by erosion from residential and open defecation

Comments are closed.