Animal Anthrax outbreak caused by slaughtering infected carcasses on and or near the pastureland, Kiruhura District, Uganda, May-October 2018

Author: Fred Monje1, Esther Kisaakye1, Daniel Eurien1, Benon Kwesiga1, Daniel Kadobera1, Alex Riolexus Ario1; Affiliation: 1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Kampala, Uganda

Summary

In May 2018, Uganda’s Ministry of Health reported human anthrax outbreak in Kiruhura District. Subsequent epidemiologic investigations confirmed link to animals. We conducted an investigation to assess the magnitude of anthrax infection in domestic ruminants; identify possible exposures, and recommend evidence-based control measures. We identified 22 case-farms and line listed 55 animal cases by October 2018. Engari sub-county (AR/10000 = 13), was the most affected. We conducted a frequency matched case-control study and found that slaughtering infected dead animals (carcasses) on and or near the pastureland (OR= 76; CI=17 – 330); and improper carcass disposal sites on and or near the pastureland where animals grazed (OR=11; CI=3.8 – 33) were the main exposures to anthrax infection in animals. We recommended immediate anthrax vaccination of domestic ruminants at risk followed by annual vaccinations and sensitization of communities; animal and medical health workers about anthrax.

Introduction

In May 2018, Uganda’s Ministry of Health reported human anthrax outbreak in Kiruhura District. Subsequent epidemiologic investigations revealed that the human victims had earlier participated in the slaughter, trading, skinning, and consumption of meat from dead animals originating from Farm X. However, the true burden and associated factors of anthrax among animals was unknown. We conducted an investigation to assess the magnitude of anthrax infection in domestic ruminants; identify possible exposures, and recommend evidence-based control measures.

Methods

We defined a suspected case as onset of sudden death with unclotted blood from body orifices in a domestic ruminant from March to October 2018 in Kiruhura District. A probable case was a suspected case positive by rapid diagnostic test (RDT), consistent with B. anthracis. A confirmed case was a suspected case positive for anthrax by PCR. To identify cases, we reviewed district veterinary anthrax records and conducted active community case finding and updated the line list. We described animal cases by animal characteristics, place, and time. We conducted environmental assessment of the anthrax affected areas, including laboratory testing of specimens from dead animals). We conducted a case-control study to compare exposures among case-farms and control-farms, frequency matched by village with a ratio of 1:4.

Results

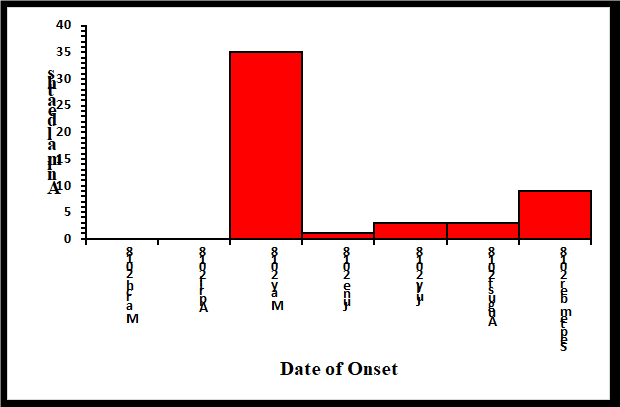

We identified 22 case-farms and line listed 55 animal cases. The epidemic curve indicated a continuous common source out-break pattern. Majority of the animals died in May, 2018. This was followed by a decline in animal deaths which later picked up and attained another peak in September, 2018 (Figure 1).

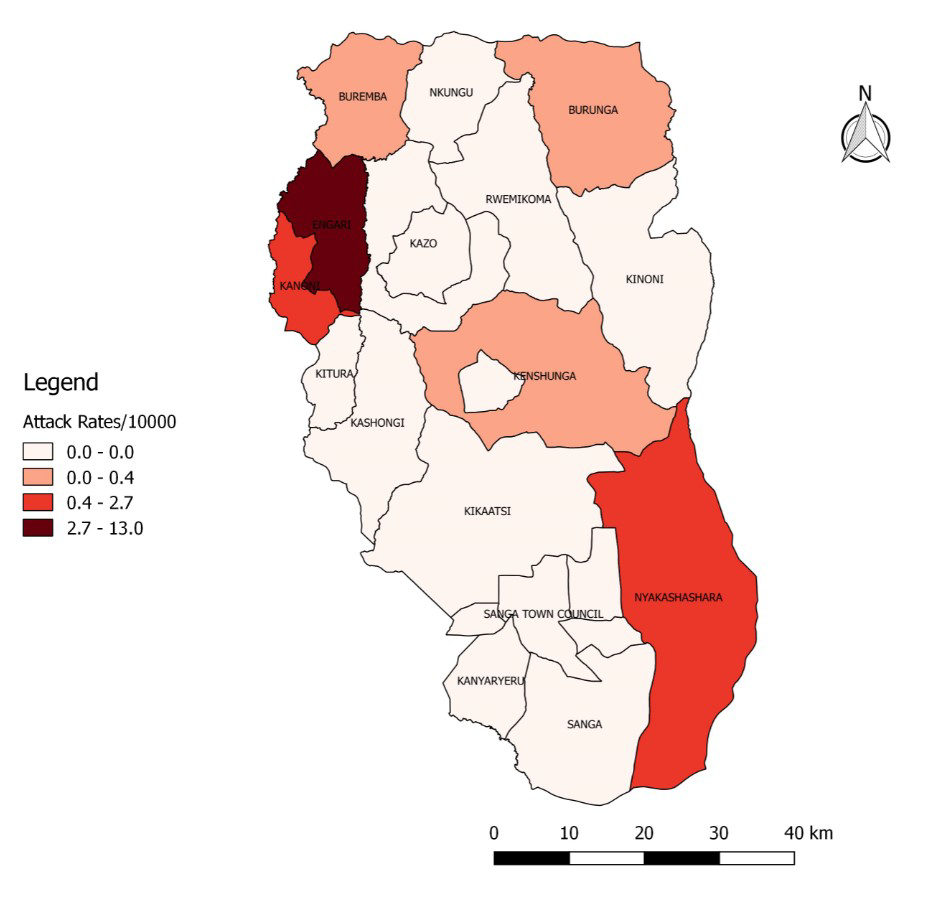

Engari sub-county (AR/10000= 13) was the most affected while Burungu was the least affected (AR/10000=0.18) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Hypothesis generation interviews

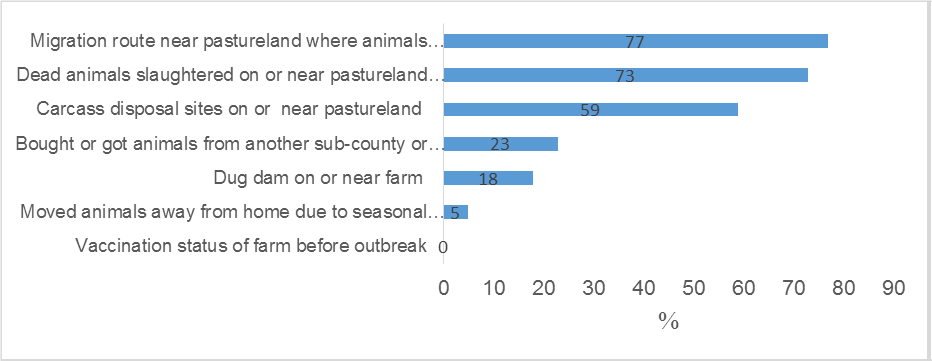

We hypothesized that the outbreak could have been associated with having migration route near pasture land where animals grazed, slaughtering dead animals on and or near pasture land where animals grazed, and disposing carcasses on and or near grazing land (Figure 3).

Environmental assessment and laboratory findings

We observed carcass disposal sites in the grazing field on the farm. We saw animals graze near the carcass disposal sites and previous slaughter sites on the farm. Migration routes in the pastureland were evident. We witnessed new dams that have been constructed prior to anthrax infection on the farm. During the study period, 7/12 livestock carcasses tested positive by RDT and the gram positive rods identified by microscopy were consistent with B. anthracis.

Case-control findings

Slaughtering infected dead animal carcasses on and or near the pastureland (OR= 76; CI=17 – 330); and having carcass disposal sites on and or near pastureland where animals grazed (OR=11; CI=3.8 – 33) were the main exposures to anthrax infection in animals.

Discussion

Our epidemiologic, laboratory, and environmental findings demonstrated that this was a continuous common source animal anthrax outbreak associated with infected carcass disposal sites on and or near the pasture land; slaughtering anthrax infected dead animals on the pasture land, and digging dams on and or near the pastureland. Improper disposal sites of infected carcass-es on the pastureland and slaughtering anthrax infected dead animals on the pastureland exposes anthrax spores that contaminate the pastureland posing a risk to cattle, goats, and sheep. The anthrax spores from the pastureland remain viable for decades (1). The spores shed by an animal dying or dead from anthrax usually provide the source of infection of other animals(2). Our findings are consistent with other studies in Bhutan, Asia that pointed out that anthrax infected carcasses led to spread of anthrax and death among animal herds (3). Similarly, findings from Bangladesh indicated that improper disposal of carcass (dead animals) was associated with repeated anthrax infections among animals (4). Furthermore, findings in North Dokota, USA also reported that death of suspected anthrax infected animals on the pasture land was associated with anthrax outbreak in animals (5).

The emergence of anthrax in Kiruhura District was not surprising because since the early 20th century, anthrax outbreaks in Uganda have repeatedly been reported in Western parts of the country – among wild animals and humans linked to contact with infected carcasses in kraals (6–8). Despite this, consistent annual vaccinations of livestock to protect animals against anthrax was never adopted.

Conclusions and recommendations

Slaughtering anthrax infected carcasses on and or near the pastureland and improper disposal of infected carcasses were associated with anthrax infection in animals. We recommended immediate vaccination of domestic ruminants at risk against anthrax followed by annual anthrax vaccinations by Ministry of Agriculture Animal Industries and Fisheries and Kiruhura Dis-trict. Enhanced sensitization of the communities; animal health workers, and medical health workers about anthrax prevention and control was also emphasized.

References

1. Carlson CJ, Getz WM, Kausrud KL, Cizauskas CA, Black-burn JK, Carrillo FAB, et al. Spores and soil from six sides: inter-disciplinarity and the environmental biology of anthrax (Bacillus anthracis). Biol Rev [Internet]. [cited 2018 Sep 19];0(0). Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/brv.12420

2. World Health Organization, International Office of Epizo-otics, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, editors. Anthrax in humans and animals. 4th ed. Geneva, Swit-zerland: World Health Organization; 2008. 208 p.

3. Thapa NK, Wangdi K, Dorji T, Dorjee J, Marston CK, Hoffmaster AR. Investigation and Control of Anthrax Outbreak at the Human–Animal Interface, Bhutan, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014 Sep;20(9):1524–6.

4. Hassan J, Ahsan M, Rahman M, Chowdhury S, Parvej M, Nazir K. Factors associated with repeated outbreak of anthrax in Bangladesh: qualitative and quantitative study. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2015;2(2):158.

5. Mongoh MN, Dyer NW, Stoltenow CL, Khaitsa ML. Risk

Factors Associated with Anthrax Outbreak in Animals in North Dakota, 2005: A Retrospective Case-Control Study. Pub-lic Health Rep. 2008 May 1;123(3):352–9.

6. Wafula MM, Patrick A, Charles T. Managing the 2004/05 anthrax outbreak in Queen Elizabeth and Lake Mburo National Parks, Uganda. Afr J Ecol. 2008 Mar 1;46(1):24–31.

7. Taylor JA. Anthrax in Ankole, Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet]. 1923 [cited 2018 Sep 18];17(1). Available from: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/19232901850

8. Coffin JL, Monje F, Asiimwe-Karimu G, Amuguni HJ, Odoch T. A One Health, participatory epidemiology assess-ment of anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) management in Western Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2015 Mar 1;129:44–50.

Comments are closed.