Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis Outbreaks caused by Coxsackievirus A24 in Three Prisons, Gulu District, Uganda, 2017

Authors: Lydia Nakiire1, J.A. Atuhairwe1, B. Masiira1, D. Kadobera1, I Makumbi2, A.R. Ario1

Summary

Background: Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (AHC) is a derivative of the highly contagious conjunctivitis virus, known as pink eye. On December 16, 2016, the Uganda Ministry of Health received an alert from Gulu District Health Office of a suspected conjunctivitis outbreak among inmates in three prisons. We investigated to determine scope, identify etiological agent, epidemiologically characterize cases, recommend evidence based interventions and prevent future outbreaks. Methods: We defined a suspected case as onset in any resident of Gulu District from November 1st 2016 onwards of red eyes and any of the following: eye itching, eye swelling, eye discharge or tearing. A confirmed case was a suspected case with positive enterovirus PCR test and sequenced as Coxsackievirus A24. We conducted medical record reviews and active case-finding in three Gulu Prisons. We conducted descriptive epidemiology and laboratory tests on conjunctivae swabs were done at CDC Atlanta. Results: We identified 493 case-persons. The overall attack rate (AR) was 16/10000 and only male inmates were affected. Age group of 20-29 was the most affected, AR=4.3/1000. Gulu Main Prison was the most affected, AR= 86/10000. The Epicurve was suggestive of a propagated transmission. 43% (9/21) of swabs tested positive for enteroviruses of Coxsackievirus A24 variant and no Ev 70 was isolated. Conclusion: The outbreaks in Gulu Prisons were caused by Coxsackievirus A24 variant and only occurred in males. We recommended provision of hand washing facilities, suspension of hand shaking and visitations during the outbreak. AHC transmission was interrupted within the prisons and community transmission stopped. Coxsackievirus A24 variant and no Ev 70 was isolated. Conclusion: The outbreaks in Gulu Prisons were caused by Coxsackievirus A24 variant and only occurred in males. We recommended provision of hand washing facilities, suspension of hand shaking and visitations during the outbreak. AHC transmission was interrupted within the prisons and community transmission stopped.

Introduction

Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (AHC) commonly known as “pink eye disease” is highly contagious and rapidly progresses in the population. It’s a disease of ocular adnexa due to inflammation of the mucous membrane of the conjunctiva. Acute form is characterized by conjunctival congestion, vascular dilatation, pain and onset of eye edema. In AHC, a prominent hemorrhagic component soon appears that is characteristic of this infection and can lead to impaired vision. The etiological agent for AHC is enterovirus in the family piconaviridae consisting of 100 serotypes delineated into four species (A-D). Serotypes enterovirus D (Species D) and Coxsackie virus A24 (species C) are responsible for most AHC outbreaks. Typically the CVA24 has an incubation period of 18-48 hours and persists for 3-7 days before resolving spontaneously. The first reported CVA24 outbreak in Uganda and Sudan occurred in June 2010 and July 2010 respectively. On December 16, 2016, the Ministry of Health (MoH) received an alert from Gulu District Health Office regarding Red Eyes outbreak among inmates in Gulu Main Prison. Gulu District is located in Northern Uganda. Based on the above information the MOH (PHFP, ESD, CPHL) and WHO responded to the outbreak to epidemiologically describe cases, confirm etiology of the outbreak, recommend evidence based interventions and prevent future outbreaks.

Methods

We defined a suspected case as onset of red eyes and any of the following: eye itching, eye swelling, eye discharge or tearing in any Gulu resident since November 1st, 2016. A con- firmed case was a suspected case-person with a positive enterovirus PCR test and sequenced as Coxsackievirus A24.

We reviewed clinical records, interviewed 100 case-persons using a case investigation form to generate hypotheses. The possible risk factors were stratified by the prisons and possible risk factors for transmission were identified. Eye swabs were collected and transported in viral transport media (VTM) to Uganda Virus Research Institute and later to CDC Atlanta for laboratory investigations.

Results

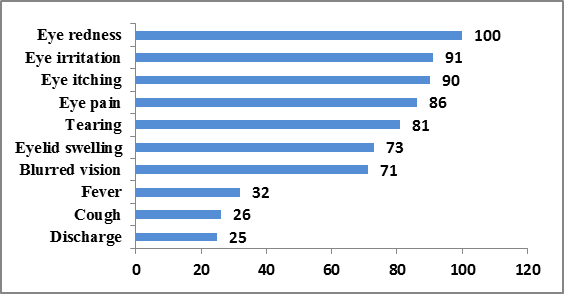

A total of 493 cases were identified. Majority of the case- persons had eye irritation (91%), eye itching (90%) and eye pain (86%).

Figure 1: Distribution of symptoms

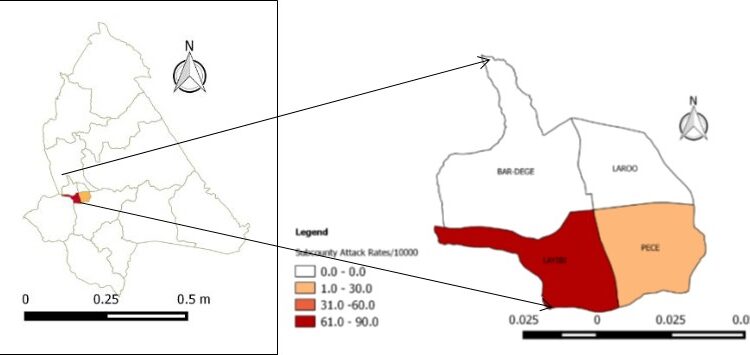

Gulu Main Prison was the most affected (AR = 86/10000) com- pared to Pece Prison (AR = 11/10000) and Gulu Remand Home (AR = 5.4/10000). Men accounted for all the cases reported (AR = 16/100000) and the age group most affected was 20-29 years (AR = 43/10000).

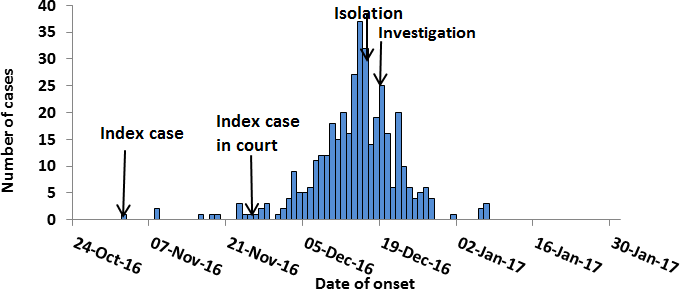

The index case was apprehended on the 14th November, 2016 and detained at Gulu Central Police Station. On 25th November he was transferred to Gulu Main Prison. There outbreak peaked on 15th December 2016. This was followed by a decline in number soon afterwards with multiple peaks in between.

Another outbreak was reported in Pece Prison where the index case had an epidemiological link with a case from Gulu Main Prison on 28th November 2016. Two days later cases increased reaching the highest peak on 8th December. Another outbreak was reported among the juveniles in the Remand Home on 2nd December after an inmate attended a court session the day before. He reported having contact with a case at the court.

Figure 2: Map of Gulu showing the two affected sub-counties

Figure 3: Epidemic curve for the A24 Coxsackie virus outbreak

Potential Risk Factors

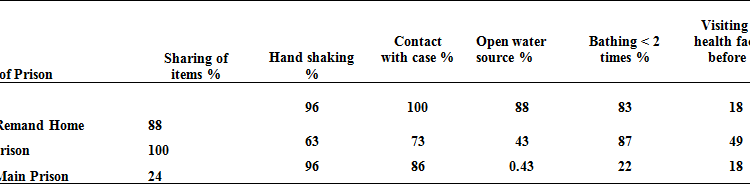

Following descriptive epidemiology, the following hypotheses were generated: sharing items, shaking hands, contact with a case, using water from an open container, bathing less than two times and visiting a facility before onset of symptoms.

Figure 4: Possible risk factors

Unfortunately, we could not conduct an analytical study to test these hypotheses.

Laboratory findings

Conjuctival swabs were tested using reverse transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT PCR) and sequenced using EV VP1 RT snPCR. Nine of the twenty one (43%) swabs test- ed positive for enteroviruses and where characterized as Coxsackie virus A24 variant.

Discussion

Enteroviruses are responsible for many large outbreaks alt- hough adenoviruses have been implicated in smaller out-breaks (Herlinda Mejía-López 2011). In this outbreak in Gulu Prisons CVA24 was identified as the causative agent and there were no isolates of adenovirus identified.

This was the second CVA24 outbreak after the one reported in June 2010 involving Uganda and Sudan one month later (Wamala 2010). CVA24 might be circulating in the Ugandan population with sporadic cases transmitting when the enabling factors like dry season, overcrowding and poor hygiene set in. The other studies where CVA24 was identified as the etiology for the outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis was in Brazil, (Tavares FN 2011, Medina NH 2016) and China (Wu, Qi et al. 2014). Men accounting for all the cases could be explained by the higher number of inmates on the male wing.

Hand to hand contact is very frequent in this setting and could have facilitated this outbreak. The highest attack rates could be explained by poor unhygienic practices among the young adults. This has been documented else- where as well, in Pakistan, the mean age for the patients was 24 (Khan A 2008) and Wu et al. had highest proportion affected among students at 23.9% , factory workers at 22.9% and children in kindergarten at 16.9% (Wu, Qi et al. 2014). In this outbreak cases were confined in the three prisons and there were no community cases.

The 2010 outbreaks involved 6818 cases and 26 districts in Uganda while 428 cases were reported from Juba in Southern Sudan (Wamala 2010). Given that the index case came from the community and caused larger outbreak in the prisons it is conceivable that congestion coupled with unhygienic conditions in the prison was favorable for rapid transmission.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This was an outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis caused by Coxsackievirus A24, confined to Gulu Prisons. At our recommendation all convicts were screened at the police and isolated if they were suspected AHC. The prison authorities provided hand hygiene facilities with support from Ministry of Health and Uganda WHO Country Office. Water taps in the prison wards in Gulu Main Prison were repaired.

References

- Herlinda Mejía-López, C. A. P.-M., Alejandro Climent-Flores and Victor M. Bautista-de Lucio (2011). Epi-demiological Aspects of Infectious Conjunctivitis- A Complex and Multifaceted Disorder, Prof. Zdenek Pelikan (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-750-5.

- Khan A, S. S., Shaukat S, Khan S, Zaidi S. (2008). “An outbreak of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis

- (AHC) caused by coxsackievirus A24 variant in Pa- kistan” Virus research 137(1): 150-152.

- Medina NH, H.-M. E., Pellini AC, Machado BC, Russo DH, Timenetsky MC. (2016). “. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis epidemic in São Paulo State, Brazil,Rev Panam Salud Publica.” Pan American Journal 39(2): 137-141.

- Wamala, J. (2010). Notes from the field: Acute Heamorrhagic conjuctivitis caused by Coxsackievirus A24v- Uganda and Southern Sudan. MMWR. 59.

- Wu, B., (2014). “Genetic Characteristics of the Cox sackievirus A24 Variant Causing Outbreaks of Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis in Jiangsu, China

Comments are closed.