A False Reported Typhoid Outbreak due to Inadequacies in Typhoid Surveillance

Authors: Joy Kusiima1* Daniel Kadobera1, Eric Ikoona2, Alex R. Ario1 1 Public Health Fellowship Programme – Field Epidemiology Track, Kampala, Uganda, 2Frontline Field Epidemiology Training Program,

Summary

The Health Management Information System reported 1549 cases of typhoid fever in 2015 and 1743 in 2016 in Nakaseke District. The Uganda Ministry of Health has provided surveillance case definitions on typhoid fever to districts; however, adherence is unknown. We investigated to confirm presence of an outbreak and evaluated adherence to the surveillance guidelines. .

We extracted patient medical records to assess adherence to surveil- lance guidelines, especially in regard to standard surveillance case definitions, and to identify any cases of perforations. We also examined freshly admitted typhoid in-patients and reviewed laboratory and data collection procedures. We collected blood specimens from 5 freshly diagnosed typhoid patients for culture confirmation.

Nakaseke District reported 560 typhoid cases during January to June 2016, compared to 291 reported cases during the same time-period in 2015. Of the admitted patients reviewed, 28% (5/18) met the surveillance case definition. Of the 1025 records reviewed in 2016, 81% (829/1025) of diagnoses were clinical only, and 19% (192/1025) had a positive Widal test as the supporting laboratory evidence.

All 5 samples from the freshly diagnosed patients cultured negative for typhoid at the reference laboratory. No cases of perforations were identified in area hospitals during the time periods under review. In conclusion, there was no evidence of typhoid outbreak in the district.

The increase in reported typhoid cases was likely due to inadequate use of standard surveillance case definitions and use of unreliable laboratory diagnostic tests. We recommend enforcing the use of surveillance case definitions for typhoid reporting, and developing laboratory capacity for typhoid diagnosis.

Introduction

In 2000,the WHO estimated about 21 million cases of typhoid cases and 210,0000 deaths [1]. These infections are highest in developing countries mainly due to poor sanitation. The burden of typhoid in sub-Saharan Africa has not been well described given the poor surveillance systems in the region; however population based studies have estimated typhoid incidence to range from 13-845 cases per 100,000 populations [2, 3]. However a recent systematic analysis reported 11·9 million (95% CI 9·9–14·7) new cases and 129 000 (75 000–208 000) deaths in 2010 [4]

Typhoid is a systematic infection transmitted via the oral faecal route; it has an average incubation period of 8-14days [5].. The clinical presentation varies from a mild illness with low-grade fever, malaise, slight dry cough to a severe clinical picture with abdominal discomfort and multiple complications. Typhoid case-fatality rate is estimated at 1% with prompt, appropriate anti- microbial therapy but approaches 30%–40% after intestinal perforation (IP) which may occur in 1%–3% of hospitalized patients [5]. Clinically, typhoid fever resembles other febrile illnesses (eg, malaria) and thus the need for laboratory confirmation[6].

The gold standard diagnostic test is bone marrow culture [7] however, routine bone marrow aspirates are not feasible in many set- tings. Therefore, the second test that is recommended is blood culture[5]. Most of the countries in developing countries lack the laboratory capacity to confirm typhoid. This is likely to result into misdiagnosis, under diagnosis or over diagnosis. Data from the Health Management Information System .(HMIS) shows a steady increase in typhoid cases from 3,470 in 2012 to 100,869 in 2015 but it is unclear whether all these are true cases or not.

On 11th June 2016, Ministry of Health was notified of a suspected typhoid outbreak in Nakaseke district. This followed analysis of surveillance data from 12 health facilities where 342 new cases were reported for week 15-21. Likewise analysis of district records in the MOH weekly surveillance system for week 18,19,20,21 estimated about 134 typhoid cases per 50,000 which is above the recommended community threshold (20 /50,000 persons)[8]. A similar threat was re- ported in the district in 2015, and it was found to be a false alarm[9]. We investigated these claims to confirm presence of outbreak and evaluate adherence to standard case definition guidelines.

Methods

We conducted this study in Nakaseke district between the 14th and 18th June 2016, in four health facilities which were selected purposively based on patient load and coverage. These included the two hospitals (Kiwoko and Nakaseke), Semuto HC IV and Kapeeka HC (III). We extracted medical records of all patients who had a diagnosis of typhoid/enteric fever from 1st December 2015 to 14th June 2016 from OPD, IPD and laboratory registers.

We reviewed laboratory testing procedures and use of protocol guidelines. Blood samples were drawn from case-patients who had high positive Widal test for surface antigen O (>1:160) for culture and sensitivity tests. The team also examined case-patients who were sent to the laboratory for typhoid screening and those who were currently admitted on the ward with a typhoid diagnosis.

We defined a suspected case as a resident of Nakaseke district with history of fever (38oC and above) that had lasted more than three days, tested negative for malaria and had at least one of the following symptoms: chills, malaise, headache, sore throat, cough, abdominal pain, constipation, diarrhea; a probable case as a patient with fever (38°C and above) that had lasted for at least three days, with a positive sero- diagnosis or antigen detection test (Widal test); and a con- firmed case as a suspected case confirmed by isolation of salmonella typhi from blood or stool by culture.

Results

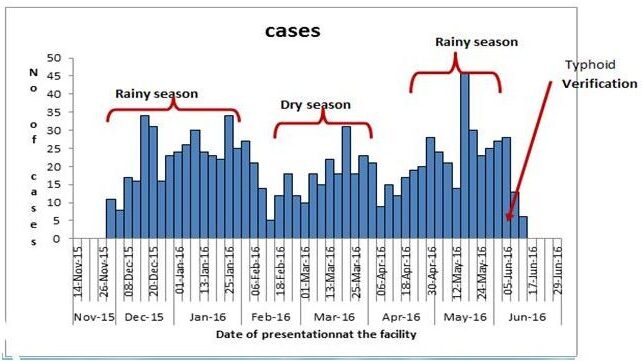

Of the 1025 case patients records extracted from the registers, 1007(98.2%) were outpatients, 829(81.2%) were clinically diagnosed. Of the18 patients admitted with typhoid diagnosis 5/18(27.8%) records adhered to the surveillance case definitions. More people were diagnosed with typhoid during the rainy season compared to the dry sea- son as shown in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Epicurve of typhoid patients , Dec 2015—Jun 2016

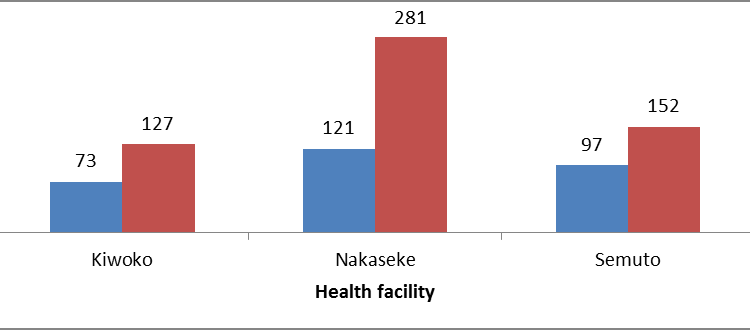

A similar typhoid verification exercise was conducted in the district in May 2015, and records for the period Jan –April 2015 were reviewed for three health facilities (Kiwoko, Nakaseke and Semuto). The number of people diagnosed with typhoid in the three health facilities in 2016 was twice that reported in 2015.

Figure 2: Comparison of suspected typhoid cases between two time periods: Jan –April (2015 and 2016)

Blood Culture All five samples taken to the Central Public Health Laboratory for cultaure and sensitivity were negative for salmonella typhi. At the district level, none of the hospitals were sufficiently equipped to confirm typhoid by culture.

Discussion

Although Nakaseke district reported typhoid cases in the Health Management Information system (HMIS), none of these cases reported in the weekly epidemiological bulletin had been confirmed using the recommended diagnostic test (blood culture), diagnosis was based on clinical symptoms. In the hospitals, the clinicians used both clinical symptoms and high surface O antigentiters (>1:160) to make a diagnosis of typhoid however, the presence of clinical symptoms characteristic of typhoid fever or the detection of a specific antibody response may only be suggestive of typhoid fever but not definitive[5]. Therefore, there was insufficient evidence to con- firm the presence of an outbreak in this district. One of the key challenges the district faces is inability to confirm the presence of salmonella typhi using culture as none of the facilities had the capacity to do so.

The Ministry of Health has instituted a hub system that facilitates transportation of blood samples from the peripheral centers to the Central Public Health Laboratory. However, this system does not favor appropriate transportation of samples for culture and sensitivity since samples from facilities are picked on designated days, yet samples for culture should be fresh and transported to the reference lab as fast as possible in a recommended transport media and temperature.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In conclusion, there was no evidence of typhoid outbreak in the district. The in- crease in reported typhoid cases was likely due to inadequate use of standard surveillance case definitions and use of unreliable laboratory diagnostic tests. We recommend enforcing the use of surveillance case definitions for typhoid reporting, and developing laboratory capacity for typhoid diagnosis we recommend training of clinicians in typhoid surveillance and strengthening the district laboratories to perform culture.

References

- John A Crump, S.P.L., Eric D. Mintz, The global burden or typhoid fever. Bulletin of World Health Organization, 2004. 82: p. 346-353.

- Breiman, R.F., et al., Population-Based Incidence of Typhoid Fever in an Urban Informal Settlement and a Rural Area in Ken- ya: Implications for Typhoid Vaccine Use in Africa. PLoS ONE, 2012. 7(1): p. e29119.

Comments are closed.