Incidence, perceptions, and experiences regarding mental illness among migrant domestic workers returning to Uganda from the Middle-East, 2019–2023

Authors: Benigna G. Namara1*, Susan Waako1, Dorothy Aanyu1, Benon Kwesiga1, Richard Migisha1, Alex Riolexus Ario1 - Institution affiliations:1Uganda Public Health Fellowship Program, Uganda National Institute of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda - Correspondence*: Tel: 256782882261 : Email: benignamara@uniph.go.ug

Summary

Introduction: The labour export business in Uganda has grown over several years with increasing numbers of women being exported to the Middle-East for domestic work. In 2023, there was an alert raised about increasing numbers of migrant domestic workers (MDWs) returning with mental illness documented at Kazuri Medical Center at the airport. We profiled these returnees, estimated the incidence of mental illness among them, and explored perceptions and experiences of key stakeholders.

Methods: To identify and characterize cases, we reviewed records from the register of mentally ill returnees’ at Kazuri Medical Center, 2019–2023. We estimated incidence as number of mentally ill returnees per 100,000 Ugandan domestic workers in the middle east per year. We conducted key informant interviews with labour export companies, returnees, and clinicians at Kazuri and Butabika to explore perceptions and experiences regarding mental illness among returning MDWs, and analysed these using inductive thematic analysis.

Results: Overall, we identified 133 mentally ill returnees, during the study period. All were female, Median age was 31 years(range:21-46). Only 81(61%) had a country of employment documented among whom 44(54%) were from Saudi Arabia. Only 31(23%) had their companies documented among which 9(29%) were unlicensed. The number of mentally ill returnees increased from 26 in 2019 to 38 in 2023. The estimated incidence of mental illness among returnees dropped from 41/100,000 in 2019 to 11/100,000 in 2020 and by 2023 was 14/100,000. Perceived contributory factors to mental illness included isolation from family, heavy workload, physical/sexual abuse and prior history of mental illness; exacerbated by stringent contract terms. Traffickers/unlicensed companies were also a threat to these workers isolating them from the protections of the legitimate labour export system.

Conclusion There was an overall decline in incidence of mental illness among Ugandan MDWs in the Middle-East from 2019–2023. Perceived contributory factors include isolation from family, work stress, prior history of mental illness, exacerbated by stringent contract terms; and traffickers may also play a role. Comprehensive mental health screening, counselling and anti-trafficking instruction should be instituted as part of the recruitment process for immigrant workers.

Background

Domestic workers, in general are faced with difficult working conditions, including long working hours, low pay, lack of legal protections, maltreatment, and social isolation. This is even worse among foreign domestic workers commonly referred to as migrant domestic workers (MDWs),who are far away from their social support structures and therefore more prone to stress, anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders as a result (1–5).

The labour export business in Uganda has grown over the last several years with increasing numbers of women being exported to the Middle-East to work as house maids(6,7). On arrival in the Middle Eastern countries, these MDWs are placed in homes, their passports taken as insurance by their employers and are then put to work. A number of them are forced to return to Uganda under various circumstances including poor health. The details of these circumstances are not well documented, and since 2019, there have been reports of these MDWs returning from abroad with mental illness.

In 2023, reports from Kazuri Medical Center, which is a health care provider facility located at Entebbe International Airport, shows an increasing number of returnees diagnosed with mental illness or depression from 2019 to date; an average of 4 per month in 2023 alone. This facility is the only Health Care provider at the Entebbe International airport and attends to all returnees in need of medical care.

On arrival from the Middle- East, these returnees are received by the aviation police following notification by the aircraft on which they travelled. They are then handed over to their relatives or taken to Kazuri Medical Centre from where they are linked to relatives or handed over to their recruiting agency.

As mental illness is increasingly becoming a matter of public health importance, we investigated these reports, profiled the migrant domestic workers returning from the Middle-East with mental illness from 2019–2023, estimated the incidence of mental illness among them and explored perceptions and experiences of key stakeholders regarding factors that might be contributing to mental illness among them.

Methods

Study design: We conducted a cross-sectional study using a mixed methods approach. We started off with a descriptive analysis of the data from mentally ill returnees at Kazuri Medical Center at Entebbe International Airport which is the first stop for returnees with mental illness. We also reviewed information from the External Employment Management Information System which keeps track of labour export in Uganda. We then conducted key informant interviews with labour export companies, returnees from the Middle East, and clinicians at Kazuri Medical Center and Butabika Hospital, the National Referral Hospital for treatment of mental health conditions.

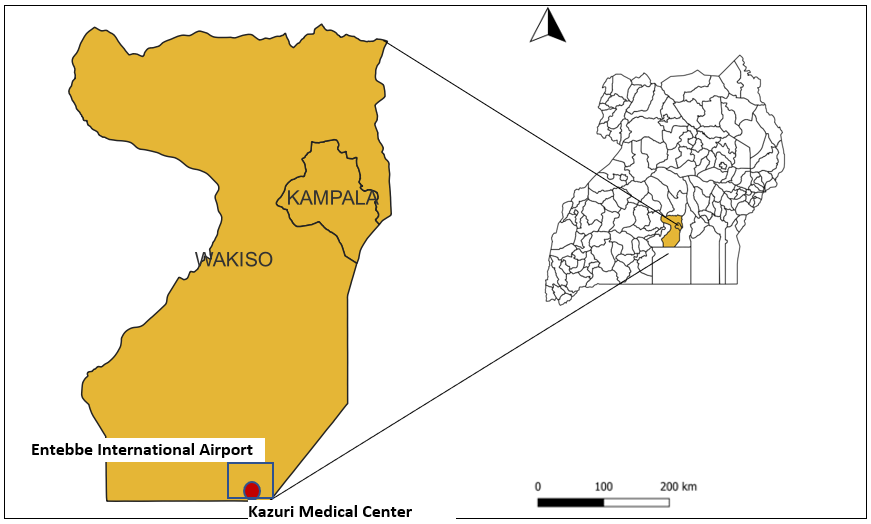

Study site, setting, and population: We conducted the investigation among domestic workers returning from the Middles East at Entebbe International Airport, Wakiso District, Kazuri Medical Center which is the first stop for returnees with mental illness; and in Kampala which is the home for most of the labour exporting companies in the country (Figure 1). Documentation of mentally ill returnees at Kazuri was instituted in 2019 and since then, all returnees from the middle east who are considered mentally ill are documented in a special records file at the facility. On arrival, each returnee suspected to have mental illness is reviewed by a clinician, any documents they have including passport, national identification, employment records are copied and retained in the file. They are given ‘first aid’ and then handed over to their labour export companies, families or other custodians with a referral or recommendation for continued mental healthcare.

Study variables and data collection

Quantitative data: We abstracted demographic and clinical data on returnees diagnosed with mental illness on return from the Middle-East from 2019 to 2023 recorded in the mentally ill returnees’ records file. We obtained data on number of MDWs in the Middle-East from the Ministry of Gender, Labour, and Social Development.

Qualitative data: We visited 7 Labour export companies where we interviewed managerial staff about their recruitment and monitoring processes as well as their knowledge, perceptions, and experiences regarding mental illness among returnees. We conducted telephone interviews with 6 mentally ill returnees and/or their relatives from whom we obtained information on their knowledge and experiences regarding mental illness among them. We also interviewed 6 returnees without mental illness to assess their knowledge and experiences. We visited Butabika National Referral Hospital which is country’s only specialized mental health institutions. We interviewed 2 clinical staff from Butabika as well as 2 from Kazuri regarding on their knowledge, perceptions, and experiences regarding mentally ill returnees. The interviews were transcribed.

Data management and analysis

Quantitative data

Quantitative data entered and analysed in Microsoft excel to determine incidence and characterize the mentally ill returnees. We considered all records in the register from 2019 to 2023 and estimated incidence as number of mentally ill returnees per 100,000 domestic workers in the middle east in the same period. We profiled the returnees by summarizing the information available in their records.

Qualitative data

To explore the perceptions and experiences regarding mental illness among these returnees, transcribed data was reviewed and organized into themes and subthemes. We used the inductive thematic analysis approach to analyze the themes and subthemes and presented findings along the themes and also quoted some representative statements by respondents.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We conducted this study in response to a public health alert and as such was determined to be non-research. The MoH authorized this study and the office of the Center for Global Health, US Center for Disease Control and Prevention determined that this activity was not human subject research and with its primary intent being for public health practice or disease control. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. §

- See e.g., 45 C.F.R. part 46, 21 C.F.R. part 56; 42 U.S.C. §241(d); 5 U.S.C. §552a; 44 U.S.C. §3501 et seq.

We obtained permission from the Directors of Butabika National Referral Hospital and Kazuri Medical Center, and verbal consent from the respondents or their care givers all of whom were aged ≥18 years. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary and that there would be no negative consequences for declining to participate in the investigation. Data collected did not contain any individual personal identifiers and information was stored in password-protected computers, which were inaccessible by anyone outside the investigation team.

Results

Profile of returnees with mental illness, Uganda, 2019-2023

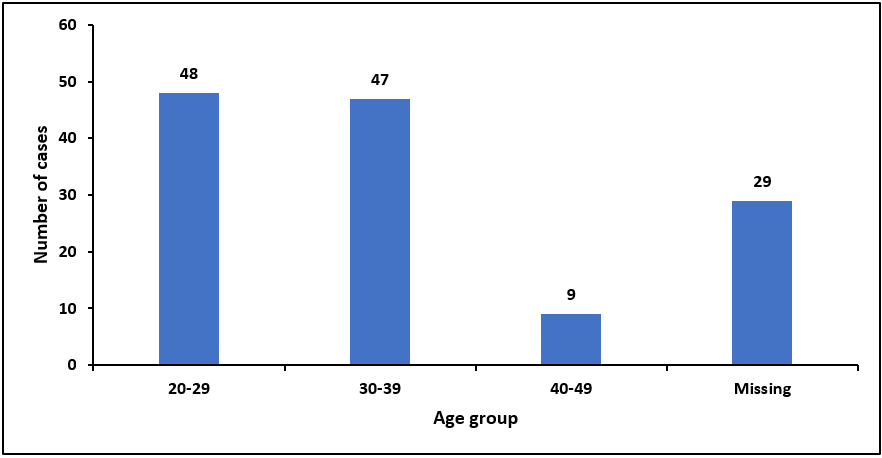

We listed a total of 133 cases: 26 from 2019,14 from 2020, 19 from 2021, 35 from 2022, and 38 from 2023. All cases were above the age of 20 years and only 9(9%) were above 40 years (Figure 2).

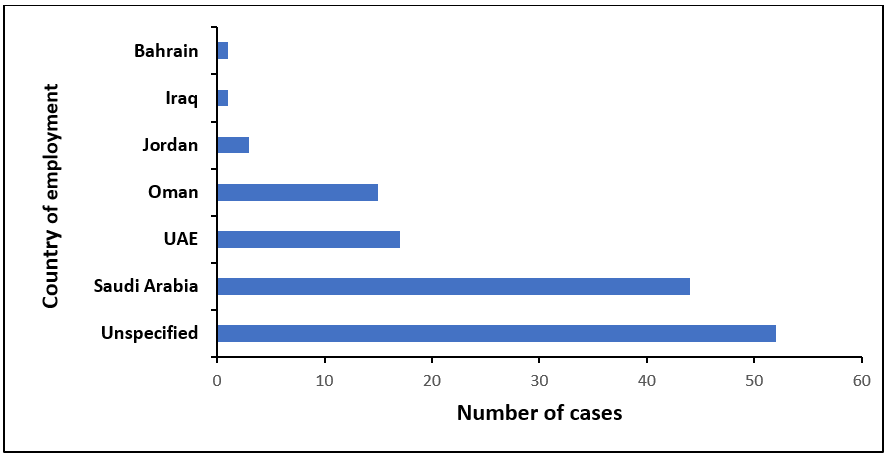

For 52(39%) of the cases, the country from which they were returning was not documented but for those with records, all were from the Middle East (Figure 3).

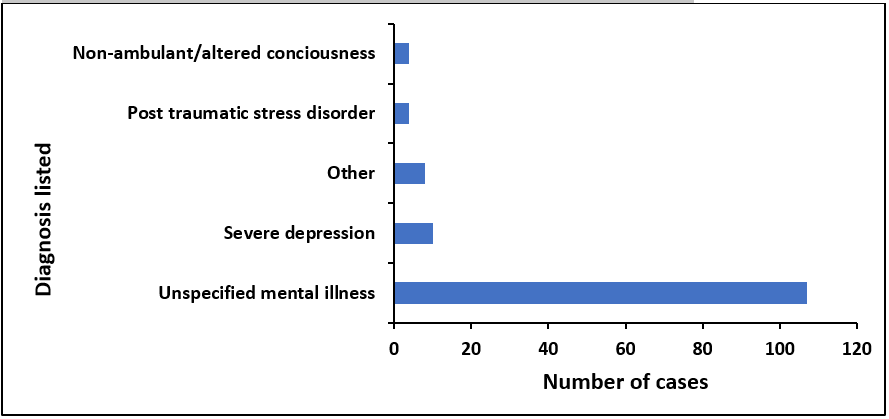

Among the 133 returnees, only 31(23%) had their recruitment companies documented at Kazuri and of these, 9 (29%) were not licensed as of the time of data collection. Among the un-licensed, 2 were previously licensed but de-licensed in 2021. For 98(74%) of the returnees, there was no documentation of how they left Kazuri Medical Center, while 23(17%) were documented as having been picked up by relatives, and 12(9%) by their recruitment companies. The cases were documented as having mental illness prompted by symptoms such as aggression, confusion, violent behaviour, abnormal speech, and muteness among others. Only 26(19%) had a specific diagnosis listed (Figure 4).

Incidence of mental illness among domestic migrant workers from Uganda in Middle East, 2019-2023

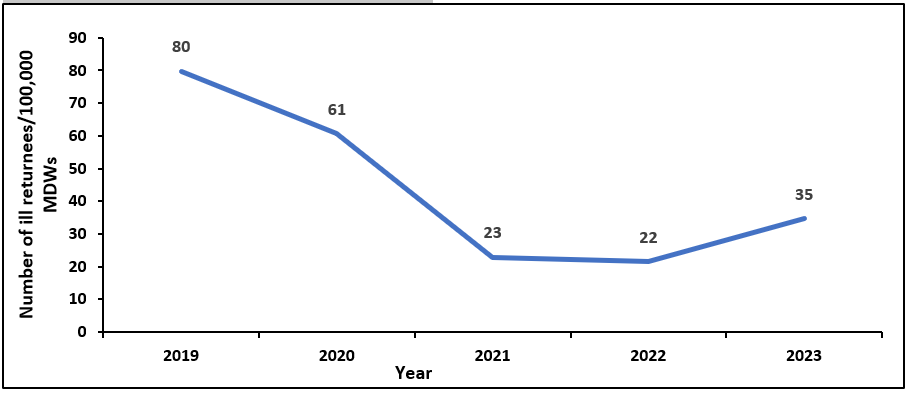

The incidence of mental illness among returnees dropped sharply from 2019 to 2021, plateaued and then rose in 2023 (Figure 5).

Perceptions and experiences regarding factors influencing mental illness among returnees from the Middle East, Uganda, 2019-2023

The themes identified included: Process of domestic labour recruitment, process of return from the Middle East, stressors/triggers of mental illness and mental illness in the general population

Process of domestic labour recruitment

We learned that there is a well-organized process involved in export of domestic workers. Companies export between 20 to 50 domestic workers every month depending on the demand from the middle east and currently, these licensed companies only export domestic labour to Saudi Arabia and not to other countries with which Uganda reportedly has no domestic-labour trade agreements. To other countries they export non-domestic labour. Six out of seven of companies visited reported exporting only domestic labour while one reported exporting both domestic (only to Saudi Arabia) and non-domestic (to other countries).

During recruitment, mental health is screened by asking the recruits and their families whether or not there is history of mental illness; no actual mental health assessment is done: Socio demographic screening is also done to ensure that all recruits are above 20 years and their families are aware and consent to the recruitment and training at designated training centers pre-qualified by the liaison companies. Only those who pass these processes are then recruited and matched with families in the Middle East after which contracts are signed between the worker and the employer, mediated by the companies. Each contract is for 2 years and includes a standard monthly pay of UGX 900,000 paid directly by the employer to the maid, decent accommodation, access to phone calls and internet.

There is also a clear and functional reporting system in place for any complaints by the worker or employer which complaints are addressed by the companies accordingly sometimes requiring the transfer of the worker to another home or return to Uganda.

Process of return from the Middle East

We learned that Kazuri Medical Centre receives all domestic workers who are deported from the middle east with suspicion of mental illness. However, it was noted that it is possible that some are met on arrival by their relatives and do not pass through the clinic. Once at the clinic, the clinicians with the help of aviation police and Uganda Association of External Recruitment Agencies (UAERA) contact the responsible labour export companies and/or patients relatives to whom they are then handed over. It was reported that some workers feign mental illness in order to return home before the end of their contracts.

Stressors/triggers of mental illness

According to the labour export companies, mistreatment of workers is not common and when it occurs, there are mechanisms in place to address it. Any employer accused of this type of assault is blacklisted by the recruitment company and liaison office and will find it difficult to get another maid.

Some companies admitted knowledge of some maids returning with genuine mental illness although they say these are rare. They pointed factors like ‘home sickness’, family problems at home, extreme weather and work load as some of the factors that cause stress leading to mental illness among those who are genuinely sick. They also report that in some cases, these girls run away or are lured away from their work places by unscrupulous agents with the promise of greener pastures. In so doing, they are in breach of their contracts and liable for arrest and so they hide from their companies. Unfortunately, because they have no support system wherever they have run to, there is no telling what happens to them there.

According to the healthy returnees, they indeed they have heard stories and even met some mentally ill returnees. When asked about what they think was the cause of the illness, some said that it was witchcraft sent by ill-wishing relatives who did not want them to prosper, others said they did not know. They denied knowledge of any serious forms of abuse among their peers i.e. physical, sexual or other that might cause extreme stress and trigger mental illness. However, they pointed out some factors including too much time away from home, not being able to communicate with family, and family problems back home that might cause stress while abroad. Some reported experiences of their colleagues sending money back home and their relatives not being able to account for it as one of the stressors their colleagues have faced. Regarding their willingness to return to the Middle East despite knowledge of mental illness among returnees, they were positive that their experience would be different.

Regarding their personal experiences as domestic workers abroad, they mentioned a variety of pros and cons. The pros included: good pay, access to support from their offices both in Uganda and in Saudi Arabia where they are able to report any misconduct of their employers and any other problems they may face during their work abroad, access to phone-calls, and internet among others. The cons mentioned included: too much time away from home, ‘too much work’, sometimes the bosses are unkind and verbally abusive, late pay, and some male bosses make sexual advances. However, they reported that for the case of the cons, they are able to report to their companies and get support. They are willing to renew their contracts and return to work abroad. They also reported that as part of the recruitment process, they had undergone work training at a designated training company, gone through a medical screening process at a designated medical facility and had been briefed on what to expect once deployed. They were aware of the reporting processes in place.

From the mentally ill returnees and/or their relatives, we learned that some maids are recruited with existing mental illness that they do not disclose. Some relatives revealed that their patients were known to have mental illness before being recruited to work abroad. but had somehow managed to pass through the medical screening process without their illness being noticed.

Most of the relatives could not give details about the circumstances surrounding the onset of illness. Some of the patients reported witchcraft as the cause of their illness while others seemed unaware of their illness but could not point out a reason why or how they left the Middle east. There were no specific reports to suggest particular known risk factors for mental illness. Some relatives reported that their patients had since fully recovered while others reported persisting mental illness.

Based on their interactions with mentally ill returnees, clinicians cited factors including isolation from family, culture shock, extreme climate, sexual assault, physical abuse, and past history of mental illness as some of the risk factors they found in some of these patients

Mental illness in the general population

We learned that there has generally been an increase in young women of all professions attending the hospital with mental illness over the last few years among whom are a few domestic workers both from abroad and local from within the country. However, hitherto there was no particular interest accorded to this group and so their non-clinical information is not well documented making them difficult to trace. The more common occupations recalled included students, teachers, hairdressers, and business women. Some of the risk factors identified include increasing rates of substance abuse, gender-based violence, work stress, academic pressure, economic stress, relationship stress, and family history of mental illness.

Discussion

Most of the mentally ill returnees with a documented country of employment were from Saudi Arabia. Among the recruitment companies identified, almost one third were un-licensed. For most of the returnees, the specific mental illness was not named. There was an overall decline in incidence of mental illness among Ugandan MDWs in the Middle-East from 2019–2023. Factors perceived to be contributing to mental illness among returnees include long durations of isolation from family back home, heavy work load, extreme weather, prior history of mental illness, and abuse.

The incidence of mental illness among these returnees also dropped from 2019 through to 2021, remained the same in 2022 and rose in 2023. This drop in 2020 followed by a rise could be due to the travel restrictions due to COVID-19 in 2020. The subsequent rise could be due to relaxing of the travel restrictions after COVID-19. Among factors perceived to be contributing to mental illness among these returnees, there was no specific report of physical or sexual abuse among the returnees interviewed but has been known to happen rarely and it is thought that most of those who experience this kind of abuse are those who are trafficked by illegal or unregistered agents (9–11).

The incidence of mental illness in Uganda is reportedly on the rise as has been severally documented in the media and published research(12–14). Uganda ranks sixth among the countries burdened with mental illness in Uganda and more females than males are affected(13,15). This likely explains why even among migrant domestic workers; the numbers are high. Documented risk factors in the country include stress from work and personal relationships, domestic violence substance abuse, poverty among others(14).

Diagnosis of mental illness is still a challenge in Uganda and the fact that only a few cases had a specific diagnosis made is an indicator of the lack of capacity even among health care workers to identify and diagnose specific mental health disorders. is generally lacking in Uganda even among health care workers.

The majority of returnees with a country of employment documented were from Saudi Arabia which can be explained by the reports that currently all companies registered to export domestic workers only do so to Saudi Arabia which reportedly the only country with which Uganda has an MOU for export of domestic workers. However, we also see returnees from other countries which raises questions about the circumstances under which these workers were taken to those countries which according to reports from the labour export companies should only be trading in non-domestic labour.

According to the External Employment Management Information System, there are currently over 10,000 jobs available in the Middle East, 72% of which are for domestic workers in Saudi Arabia (16). Most of the returnees with documented countries from which they were returning came from Saudi Arabia. This matches reports and figures from the ministry of gender, labour and social development which estimate that an average of 400 Ugandan migrant workers are exported daily to mainly Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar with Saudi Arabia alone taking almost 90% of the labour exported(7,17). Given the reports that licensed companies only export domestic labour to Saudi Arabia and not to other countries, there is a question about why a considerable number of these returnees are from Oman, Jordan among others. Are there systems in place to protect the workers in these countries?

Since 2019, the number of labour export companies continues to grow translating into a corresponding increase in number of domestic workers exported. Still in 2019, Uganda suspended the trading licenses of several labour export companies. citing several violations of human rights (6, 8,17,18,). Among the returnees registered at Kazuri, only 31(23%) had their recruitment companies documented, of which 9 (29%) are not licensed today according to the EEMIS register of labour export companies(8). Some of these unlicensed companies are among those that had their licenses suspended in 2019 while for others there is no documentation of them ever being licensed (8,16). This raises a question about whether those whose companies were not documented by Kazuri were recruited by licensed agencies or independent agents or traffickers as has been known to happen(9).

The domestic labour export industry has been streamlined to ensure protection of migrant domestic workers. All registered companies are available in a database accessible to the public so that potential recruits are able to verify their companies(16). There are also clear reporting mechanisms incase of maltreatment by employers. Despite this, as with many other industries, there are reports of illegal agents who are not amenable to the existing regulatory mechanisms and therefore jeopardize the safety of these workers after unlawfully recruiting them. There is also the possibility of some legal agents that do not prioritize the safety and wellbeing of their recruits. This is in keeping with documented reports on the same(11,12).

All these mechanisms should offer a certain degree of protection to domestic workers abroad. Nonetheless there are still several potential stressors faced by these workers that may not be amenable to a streamlined recruitment system for example size of the workload, isolation from family, stringent terms of contract especially duration, among others. Physical and sexual abuse may also be perpetrated against domestic workers despite the systems in place to mitigate this as no system can be full proof. Existing mental illness is also a risk factor among these workers, one which the screening processes are probably not equipped to detect. This is evidenced by the fact that among the returnees we documented were some with known history of mental illness that had precluded them from alternative occupations. This indicates a gap in the medical screening process and highlights the need to address this issue accordingly.

Limitations

We estimated the numbers of mentally ill returnees using records from Kazuri Medical Center which might have been an underestimation given the possibility that not all the mentally ill pass through the facility. Documentation of the mentally ill returnees at Kazuri Medical Center was not complete as evidenced by a lot of missing/unspecified information.

Conclusion

There was an overall decline in incidence of mental illness among Ugandan MDWs in the Middle-East from 2019–2023. Perceived contributory factors include isolation from family, work stress, prior history of mental illness, exacerbated by stringent contract terms; and traffickers may also play a role.

Recommendations

Labour export companies should consider revising the duration of the contracts of domestic workers to allow more flexibility and reduce the stress associated with having to spend 2 whole years isolated in a foreign country.

Thorough and comprehensive mental health screening should be done during the recruitment process before these workers are exported.

Investigations into trafficking of workers by independent agents working outside EEMIS should be conducted.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest.

Authors contribution

BGN, SW, DA and BK: participated in the conception, design, analysis, interpretation of the investigation findings and report writing. BK and RM reviewed the report. BGN wrote the draft bulletin article and BK, RM and ARA reviewed the article to ensure intellectual content and scientific integrity.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the management of Kazuri Medical Centre and Butabika National Referral Hospital as well as the labour export companies that provided information during this investigation.

Copyrights and licensing

All materials in the Uganda Public Health Bulletin is in the public domain and may be used and reprinted without permission; citation as to source; however, is appreciated. Any article can be reprinted or published. If cited as a reprint, it should be referenced in the original form.

References

- Hall BJ, Pangan CAC, Chan EWW, Huang RL. The effect of discrimination on depression and anxiety symptoms and the buffering role of social capital among female domestic workers in Macao, China. Psychiatry Res. 2019 Jan;271:200–7.

- Choy CY, Chang L, Man PY. Social support and coping among female foreign domestic helpers experiencing abuse and exploitation in Hong Kong. Frontiers in Communication [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 21];7. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2022.1015193

- Zainal KA, Barlas J. Mental health, stressors and resources in migrant domestic workers in Singapore: A thematic analysis of in-depth interviews. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2022 Sep 1;90:116–28.

- Molarius A, Metsini A. The Association between Time Spent in Domestic Work and Mental Health among Women and Men. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 11;20(6):4948.

- Wong A. Identifying work-related stressors and abuses and assessing their impact on the health of migrant domestic workers in Singapore. [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2024 Feb 21]. Available from: https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcle/collections/graduateresearch/42591/items/1.0075754

- Monitor [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Cabinet halts registration of new labour companies. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/cabinet-halts-registration-of-new-labour-companies-3880820

- Monitor [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Labour export earned govt Shs25b in two years. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/business/markets/labour-export-earned-govt-shs25b-in-two-years–4521862

- Kamusiime W. List of Labour Export Companies Whose Licenses Have Been Cancelled/Suspended [Internet]. Uganda Police Force. 2021 [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.upf.go.ug/list-of-private-recruitment-companies-suspended-by-the-ministry-ofgender-labour-and-social-development/

- Business & Human Rights Resource Centre [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Middle East: 89% Ugandan migrant workers subject to human trafficking, says Global Fund to End Modern Slavery. Available from: https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/middle-east-89-ugandan-migrant-workers-subject-to-human-trafficking-says-global-fund-to-end-modern-slavery/

- Ministry of Internal Affairs Uganda [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 12]. Trafficking in Persons Report 2021. Available from: https://mia.go.ug/reports/general/trafficking-persons-report-2021

- Trafficking in Persons Report 2023.

- Blogs BG. BMJ Global Health blog. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. The silent mental health crisis among men in Uganda. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjgh/2023/10/22/the-silent-mental-health-crisis-among-men-in-uganda/

- https://www.apa.org [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 29]. Mental health in Uganda. Available from: https://www.apa.org/international/global-insights/uganda-mental-health

- Monitor [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 29]. 30 percent of Ugandans have mental disorders, new study. Available from: https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/30-percent-of-ugandans-have-mental-disorders-new-study-4420098

- Asiimwe R, Nuwagaba-K RD, Dwanyen L, Kasujja R. Sociocultural considerations of mental health care and help-seeking in Uganda. SSM – Mental Health. 2023 Dec 15;4:100232.

- EEMIS | Companies [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Available from: https://eemis.mglsd.go.ug/companies?s=&search=

- Independent T. Gov’t collects UGX 7Bn revenue from labour export companies in seven months [Internet]. The Independent Uganda: 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.independent.co.ug/govt-collects-ugx-7bn-revenue-from-labour-export-companies-in-seven-months/

- Kamusiime W. LIST OF LICENSED PRIVATE RECRUITMENT COMPANIES LICENSED BY THE MINISTRY OF GENDER, LABOR AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT AS OF 20TH SEPTEMBER, 2018 [Internet]. Uganda Police Force. 2018 [cited 2024 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www.upf.go.ug/list-of-licensed-private-recruitment-companies-licenced-by-the-ministry-of-gender-labour-and-social-development-as-at-20th-september-2018/

Comments are closed.